- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

“… HERE YOU ARE KNOWN TOO WELL”–

Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

Lisa Fittko, née Ekstein, was a resistance fighter against National Socialism. Her political life began in Kreuzberg. Before that, she lived with her parents, who were members of the Jewish community until 1919, in impoverished conditions in Budapest and Vienna. Reluctantly, she came to Berlin as a teenager, refused formal education, and became involved in communist groups and proletarian sports clubs from 1924 onwards. In 1928, she joined the German Communist Party (KPD) and worked for Rote Hilfe to support political prisoners and persecuted people. She earned little but could afford an apartment at Belle-Alliance-Platz (now Mehringplatz).

Even before the National Socialists came to power, Lisa Ekstein had already established a left-wing network. In her memoirs (1985 and 1992), she linked the incisive political events from the 1929 Bloody May and the Reichstag fire to the anti-Semitic boycott on April 1, 1933 with the places in her Kreuzberg neighborhood.

In February 1933, she left Kreuzberg because she had become “too well known” there, went underground in Friedrichshain, and fled Berlin in the summer of 1933. Between 1940 and 1941, she helped many people escape across the French-Spanish border. In exile, she presumably took the name of her future husband, Hans Fittko, even before they were married.

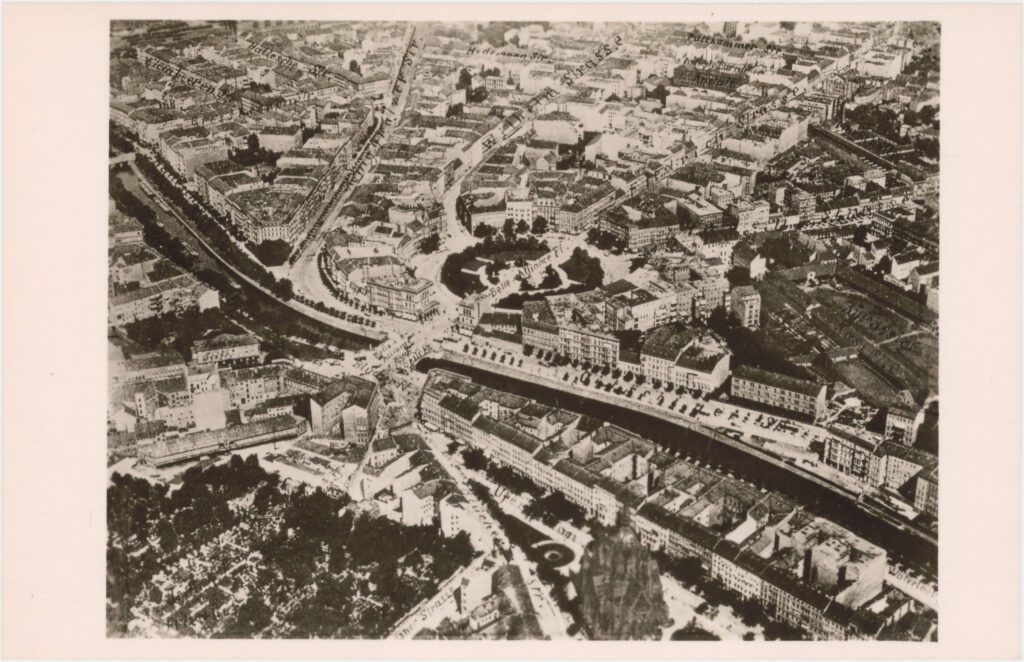

The exact locations of her political activities in Berlin, especially in 1933, are little known. Thanks to Peter Plewka’s postcards, her involvement in the everyday proletarian life around today’s Mehringplatz can be better understood.

Subtopics

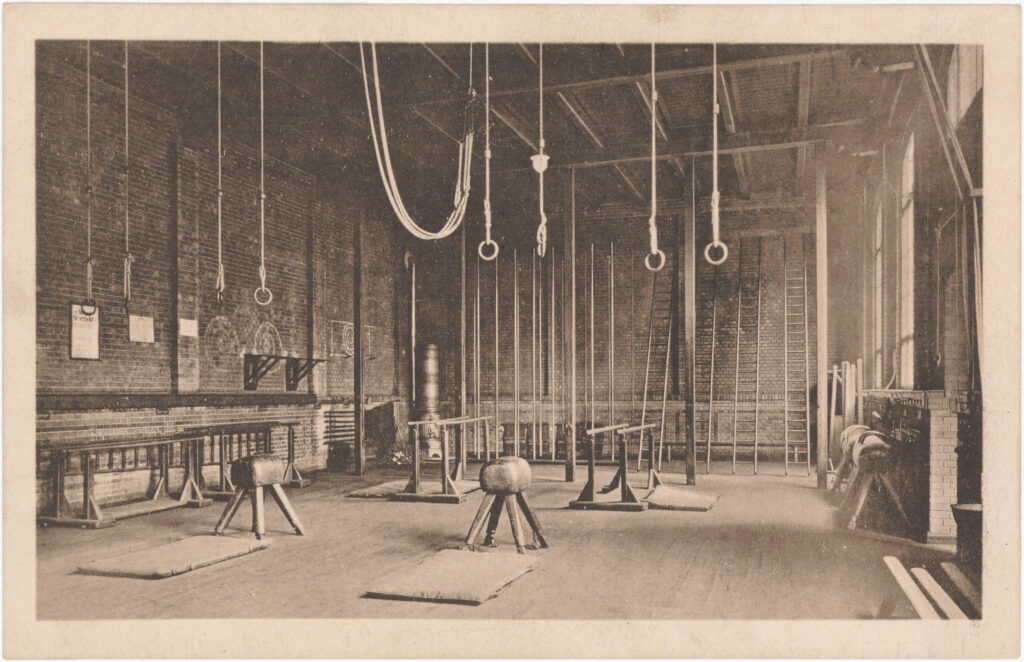

Youth between sport and activism

Lisa Ekstein’s youth was marked early on by the class struggle and the defense against fascism. She felt that her parents’ expectations of higher education and university were a waste of time. Even as a 15-year-old, she saw her role in the communist movement: for example, she took on a leading role in Group 16 (Berlin-Kreuzberg) of the German Communist Youth League. The Red Sports movement played a major role in her political commitment, enabling her to defend herself in the event of attacks by the Stahlhelm or confrontations with the police. The proletarian sports movement inspired the masses in Berlin in the 1920s. One of the communist Red Sports clubs was the Freie Turnerschaft (Free Athletes), to which Ekstein belonged and which reported in 1929 that female athletes now made up half of its members.

Ekstein’s disappointed hopes on the eve of National Socialism

Lisa Ekstein’s Berlin was not only contradictory, it oscillated between extremes. The city of her memory oscillated between a left-wing spirit of optimism––the Berlin of Bert Brecht, Claire Waldoff, Erich and Zenzl Mühsam and Neues Bauen––and the crisis of the 1920s with unemployment, poverty, and anti-Semitism. Ekstein countered these contradictions with her hope for the defeat of National Socialism and a communist future, which she outlined retrospectively in her work “Escape Through the Pyrenees”: “There were always more and more unemployed in this Berlin, always more hunger. Brown-shirted mobs callously murdered their political opponents and tried to terrorize the city. Still, the Berlin of my memory remains fair and inspiring; we stood ready to defend it from the Nazi menace, and we sang, ‘Yonder on the horizon stands the Fascist threat, but our day is not far off.’” While the “brown-shirted mobs” she mentioned still had to reckon with resistance in the Kreuzberg of the Weimar Republic, this was no longer the case from 1933 at the latest.

“But here – in the middle of our Kreuzberg?”

Ekstein’s reaction to the National Socialist takeover

Lisa Ekstein was shocked by the National Socialist takeover on January 30, 1933. Although she had been aware of fascist terror since the mid-1920s, she was taken by surprise that Hitler’s appointment as Reich Chancellor by Hindenburg was accepted. Nevertheless, she was not yet ready to give up hope: If the German workers would only understand what National Socialism would entail once the extent of the tyranny became known abroad, then the regime would not be able to hold on for long.

What dismayed her was the lack of organized resistance in Berlin and especially in Kreuzberg: her statement “That’s Berlin here!” still sounds incredulous in her memoirs “Solidarity and Treason” in 1992. The experience of the Nazi takeover on January 30, 1933 was etched topographically into her memory. Her familiar surroundings and the frequently used Hallesches Tor station became alien to her. When she got off the elevated train at Hallesches Tor that day, she heard the roar of the Brown Shirts and was perplexed that the takeover had been accepted in her neighborhood as well. In her memoirs, she asks: “But here – in the middle of our Kreuzberg?”

Everyday life in Kreuzberg and Ekstein’s disillusionment in January 1933

January 1933 marked a political turning point for Lisa Ekstein. As a child, she had starved during the First World War and had been involved in street fights in Berlin in the 1920s; she had therefore already experienced crises and political violence. But the experience of the National Socialist takeover on January 30, 1933 shook her to the core. She assumed that the immediate response would be a general strike like the Kapp Putsch of 1920. Instead, she was confronted with the apathy of her neighbors: Everyday life in Kreuzberg went on. While the cries of “Sieg Heil” rang out across Belle-Alliance-Platz, she describes in her memoirs the “people who came home from work as usual at this time of night. Some looked around, some hesitated, jackets and coats were pulled up tighter in the January air. Many walked faster than usual. Did they just take note of it all? Some looked away, went in a different direction. Something was wrong here, I saw it, but it couldn’t be true.”

Lisa Ekstein as a witness to the ‘national community’ at the beginning of National Socialist rule

In disbelief of the fact that National Socialism was also being accepted unchallenged “in the middle of our Kreuzberg,” Lisa Ekstein walked from Belle-Alliance-Platz to Wilhelmstr. and later to the Brandenburg Gate on January 30, 1933. She probably passed the houses diagonally opposite her apartment, which her neighbors would decorate with swastika flags in the following years. At the Reich Chancellery, she saw “the murderers marching” and the crowd cheering them on, as she describes in her memoirs. She saw “shining eyes, screaming mouths, roaring” and had to flee as she stood out because she did not shout “Sieg Heil” and did not raise her arm in the Hitler salute. In the end, she had to admit to herself that the communist movement was not prepared for resistance to National Socialism.

Going underground

Lisa Ekstein was fundamentally shocked by the broad support and cheers for fascism. In her memoirs, she noted: “Just get out from here, back home.” But this home was not just her apartment at Belle-Alliance-Platz 4, but also the pastry shop in Gitschiner Str., where she had discussed, played chess and eaten liver pâté with her comrades. Fittko had reluctantly moved to Berlin, but by then her Kreuzberg neighborhood had become the social center of her friendships, the place of her independence from her parents and her political home.

She would not give it up without a fight: “And now? Many would have to disappear. Go into hiding, yes, but we wouldn’t disappear. Never. The fight against fascism had to go on, especially now. Underground,” as she recalls in her memoirs.

Escape from Kreuzberg

At the end of the Weimar Republic, the police and Sturmabteilung (SA) already knew Lisa Ekstein to be an active communist. She was “known too well” in Kreuzberg as an activist of the opposition and in danger of being arrested. She had to give up her home in Kreuzberg in the spring of 1933 and go into hiding. She had to leave behind her own apartment, Belle-Alliance-Platz and Hallesches Tor. For her, a piece of the happy Berlin of her youth was lost: As Lisa Fittko (previously Ekstein) noted in her memoirs, this Berlin of a left-wing promise of happiness had included not only Brecht, Zille, the Bauhaus and Friedrich Wolf, but also Claire Waldoff, who had sung about Hallesches Tor. In Waldoff’s chanson, “Hannelore,” the “most beautiful child from Hallesches Tor,” lives as a subtenant with a flower woman and enjoys Berlin’s permissiveness: androgynous with a bobbed head, she spends the night, takes cocaine, boxes, dances and has a “Bräutjam und ’ne Braut” (a husband and a wife). This other Berlin was shattered before Lisa Ekstein’s eyes. However, she took her gramophone, the songs from the Threepenny Opera and Marlene Dietrich with her underground to Friedrichshain in Gubener Str. – a neighborhood she didn’t know her way around very well.

Lisa Ekstein’s resistance actions in the spring of 1933

After the National Socialist takeover, one of Lisa Ekstein’s first practical questions was: “Where is the mimeograph machine?”, as she writes in her memoirs. She and her comrades wanted to shake up the Berlin proletariat and report on the “SA raids on workers” pubs and apartments.” When she went into hiding, she took her typewriter with her and typed in constant fear that her neighbors in Friedrichshain would hear her.

After the suppression of freedom of the press, the comrades no longer distributed leaflets, but posted them in stairwells. They planned their own newspaper. But as events unfolded rapidly, they had to come to terms with life underground. Since the arrests also affected their circle of acquaintances, they were unable to go beyond pamphlets. Fittko (previously Ekstein) still remembered the inscription on one leaflet in exile in Chicago: “DEATH TO FASCISM – THE FIGHT CONTINUES!”

Terror at the beginning of the National Socialist tyranny

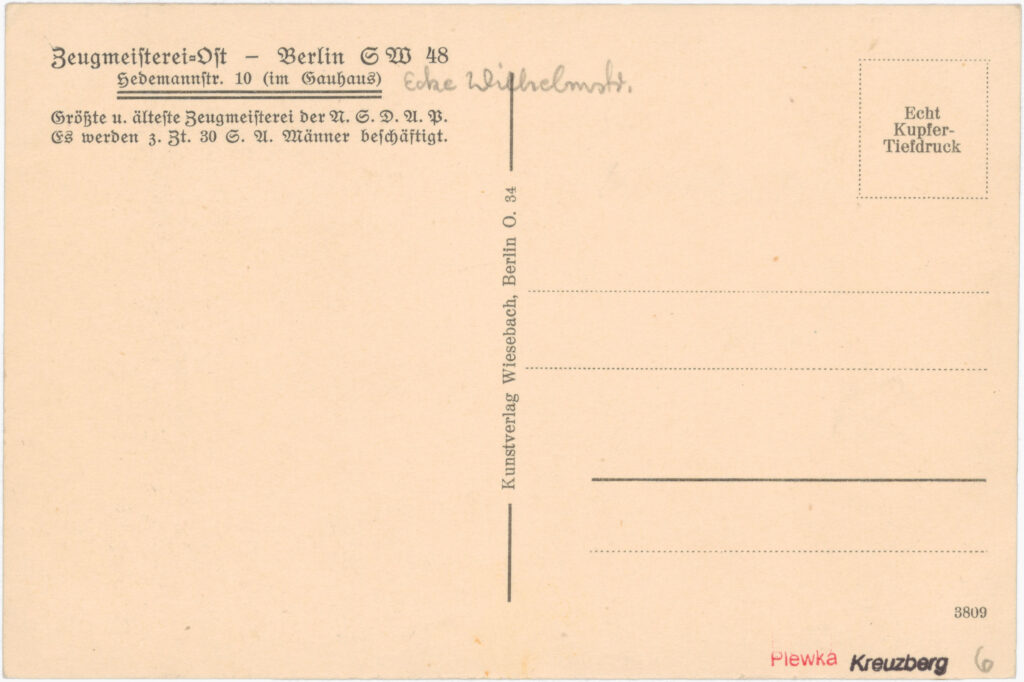

In the first weeks of National Socialist rule, the arrests and murders surrounding Lisa Ekstein increased. The first person she mentioned by name was Erich Meier from Spandau. This prompted her and her comrades-in-arms to “make the truth about the torture and murders known outside,” as she wrote in her memoirs. She collected reports and evidence, interviewed people released from so-called “protective detention.” She researched torture and murder in concentration camps in Oranienburg, Hedemannstr. and Columbiahaus. According to Lisa Fittko’s (previously Ekstein) own statement, the reports reached London, Paris and New York, “but the world didn’t want to hear us,” as she resignedly states in her book “Escape Through the Pyrenees.” The cellars of the SA barracks in Hedemannstr., where the communist and democratic opposition from Kreuzberg and Charlottenburg had been taken in February 1933, recur in her memoirs. Hedemannstr. was representative of the “cruelest tortures” and the “SA hells throughout the country,” as she wrote in her memoirs.

The Gauhaus of the NSDAP was located on the corner of Hedemannstr. and Wilhelmstr., where, according to the postcard, “currently 30 S.A. men were employed.” There were several SA quarters in Hedemannstr., which served as an early concentration camp from the beginning of March to June 1933.

Witness to the anti-Semitic boycott on April 1, 1933

Lisa Ekstein was threatened as a communist. According to Nazi ideology, she was also considered Jewish and was therefore always at risk. However, the anti-Semitic persecution did not initially play a major role for her. One exception is her report on the anti-Semitic boycott on April 1, 1933: on Alexanderplatz, she saw an SA line up in front of a shoe store. Without hesitation, she made her way through the shouts of “Don’t buy from Jews!” The sales clerk, to whom her solidarity was directed, pointed out that she should not have entered. Afterward, she realized: “How could I, I’m illegal”, as she recalls in her memoirs. This leads to the conclusion that Lisa Ekstein saw herself primarily as an “illegal”, as a communist in hiding who was in danger and ignored the fact that the anti-Semitic cries could also have been directed at her. She interpreted the census in June 1933, from which she hid with her brother in Charlottenburg, as persecution of the “illegals”. The fact that the aim was to determine the number of Jews did not occur to her.

Although there are photographs of the anti-Semitic boycott, there are no picture postcards in the Peter Plewka Collection. The boycott of supposedly Jewish stores – often under the banner “Germans don’t buy from Jews” – had precursors even before 1933. The German-national highlighting of goods was already common in the early 1930s.

“Don’t stand out!”– Everyday life in the underground

Anyone who went into the resistance and underground during National Socialism lost their everyday life, their possessions, their job, and their place of residence. Lisa Ekstein lost her apartment, her job as a foreign language correspondent and her life “in the neighborhood”. Illegality brought with it an everyday life under the motto “Don’t stand out!”. She couldn’t stay in hiding during the day, but went for walks, wandered vigilantly through department stores, sat in a café or in the park as long as it was inconspicuous and rode her bike. In her memoirs, Lisa Fittko (previously Ekstein) meticulously described the effort of surviving underground and the daily hardships. In contrast to her precise descriptions of everyday life in the underground, it is astonishing what she left out: she did not mention her pregnancy and abortion, she called her lover August Laß Bruno and ignored the fact that he was released after his arrest by the Gestapo and betrayed comrades. Her biographer Eva Weissweiler emphasizes that Lisa Fittko also omitted the smashing of the trade unions and the burning of books from her memoirs.

Escape and aiding in escape

Before Lisa Ekstein fled in the summer of 1933, her life became increasingly precarious: in the Café Weiß-Csarda in Kommandantenstr., her father Ignaz Ekstein had told her before she left that her parents were unable to help her financially.

When she had to move out of her Friedrichshain hiding place, her life became even more precarious. In her memoirs, Lisa Fittko (previously Ekstein) described “not so much the fear and panic, but the effort of going into hiding: ‘Riding the subway back and forth for a while, but not falling asleep! Always watch out. How endlessly long such a day can be!’” She took the train to pass the time and to gather information. In March 1933, she heard about the murder of the communist Erich Meier at Gleisdreieck. But she wanted to stay, not “desert”. In the summer of 1933, she finally had to flee because other people who had been arrested – assuming she was out of the country – had described her to the Gestapo.

Her escape to Czechoslovakia via Bodenbach enabled her to later become one of the most important escape agents as Lisa Fittko. She became famous because in 1940 and 1941 she brought many people who had to flee from National Socialism across the French-Spanish border – including the Berlin philosopher Walter Benjamin, who committed suicide after crossing the Pyrenees under the threat of being handed over to the Gestapo.

Author

Lea Fink

LITERATURE AND SOURCES

Fahrenwald, Käthe: „Jungmädchen und Frauen tummeln sich“, in: Freie Turnerschaft Groß-Berlin Vorstand und Hauptfestausschuss (Hg.): 10 Jahre Freie Turnerschaft Gross-Berlin e. V., Berlin 1929, S. 7.

Fittko, Lisa: Mein Weg über die Pyrenäen. Erinnerungen 1940/41, München/Wien 1985.

Fittko, Lisa: Solidarität unerwünscht. Erinnerungen 1933 -1940, München/Wien 1992.

Gerlach, Hans Jörgen: Der Engel der Geschichte. Zum Tod der Widerstandskämpferin Lisa Fittko, in: Zwischenwelt (Zeitschrift für Kultur des Exils und des Widerstands), 22. Jg., Nr. 1/2. Wien August 2005, S. 7–9.

Heiratsurkunde, Elisabeth Ekstein, in: Sammlung Berlin, Deutschland, Heiratsregister 1874-1936, Standesamt Berlin VIII, Urkunde Nr. 37, Landesarchiv Berlin.

Kaderüberprüfungskommission Amsterdam: Dossier über „Lewin, Elisabeth, Berlin“, BA: RY 1/69, 24. August 1937.

Maier, Lilly: Zwischen Rettung und Selbsthilfe: Jüdische Retterinnen in Frankreich während der Shoah [Dissertationsschrift, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, im Erscheinen begriffen].

Sandvoß, Hans-Rainer: Widerstand in Kreuzberg, Berlin 1997.

Schünke-Bettinger, Trille: Nichts erinnert an diese frühe Folter- und Mordstätte der Nazis inmitten Berlins: Das SA-Quartier in der Hedemannstraße. In: Länderbeilage Berlin. Antifa Sept./Okt. 2023.

USC Shoah Foundation: Interview mit Lisa Fittko, Jewish Survivor Lisa Fittko Testimony, 8 Stunden, 1999.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rV00DBLWt18

Weissweiler, Eva: Lisa Fittko. Biographie einer Fluchthelferin, Hamburg 2024.

![This advertising card propagates that “The German […] should drink German liqueurs”. Carl Lampe A.G., Hallesche Str. 17, ca. 1931, SPP / FHXB 5419.](https://sammlung-plewka.friedrichshain-kreuzberg-museum.de/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/fittko-10-5419r-1024x678.jpg)

![This advertising card propagates that “The German […] should drink German liqueurs”. Carl Lampe A.G., Hallesche Str. 17, ca. 1931, SPP / FHXB 5419.](https://sammlung-plewka.friedrichshain-kreuzberg-museum.de/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/fittko-10-5419v-rueckalsvord-1024x676.jpg)