- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

HIDDEN STORIES:

WOMEN IN KREUZBERG

Even before the women’s centers were founded in the 1960s and 1970s, women were already shaping social and economic life in Kreuzberg. Nowadays, the 1920s are mainly known for the image of the dazzling “New Woman”, but the everyday life and living environment of the vast majority of women remain invisible. They worked in factories, ran small businesses and were involved in social movements.

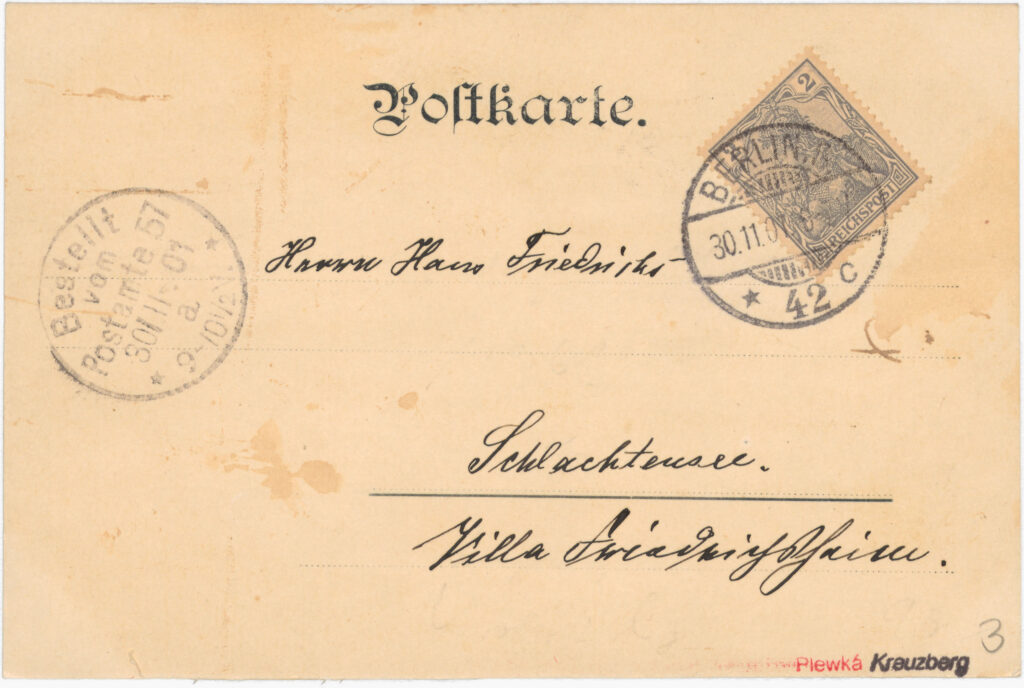

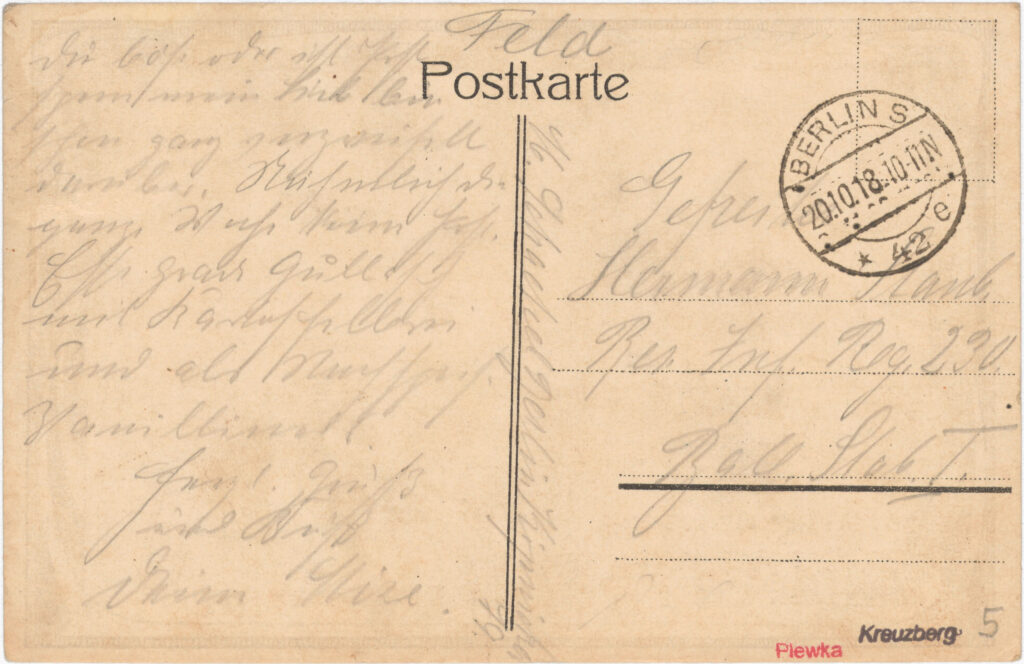

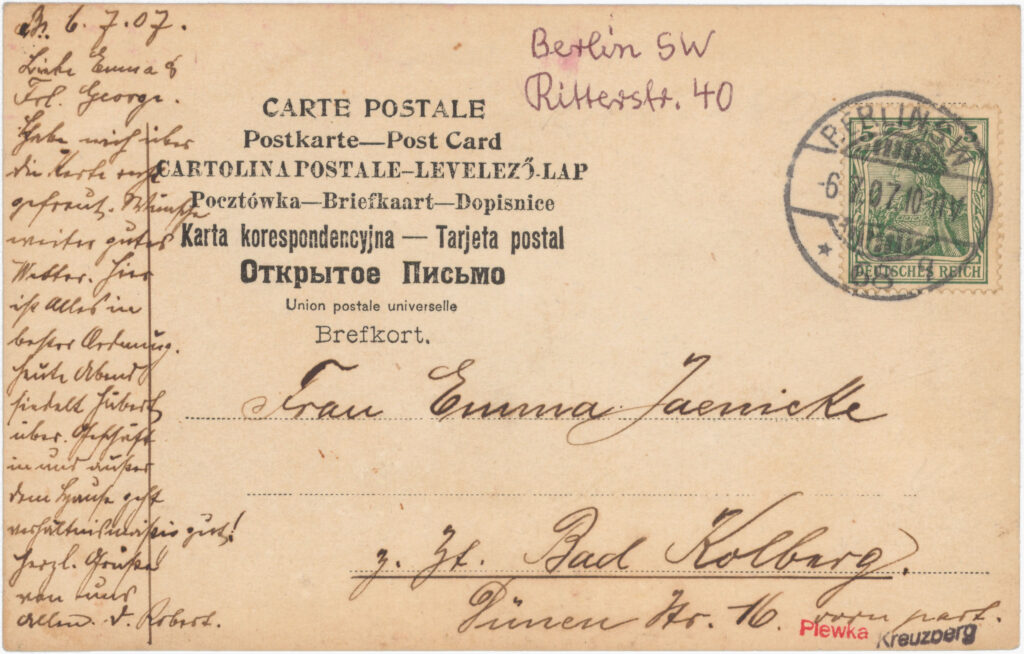

Since the end of the 19th century, women sought equal rights with men and fought to vote and work under better conditions. However, despite their central role in society, many of their stories and places remained unknown for a long time. Even photographs and postcards from this period rarely provide insights into the lives of women. This invisibility is an expression of a lack of social recognition as well as political and economic inequalities.

Women’s spaces are also underrepresented in the Peter Plewka collection, and the worlds of their everyday lives only appear in excerpts. Many places lack any images, such as meeting places for lesbian women. The collection therefore does not reflect reality – many aspects of women’s lives and activities are not represented.

In the following, the collection of Peter Plewka is used to trace the stories of women in Kreuzberg at the beginning of the 20th century: Working women, meeting places of the women’s movement and the places and conditions of women’s lives come into view.

Invisible: Lesbian clubs

and meeting places

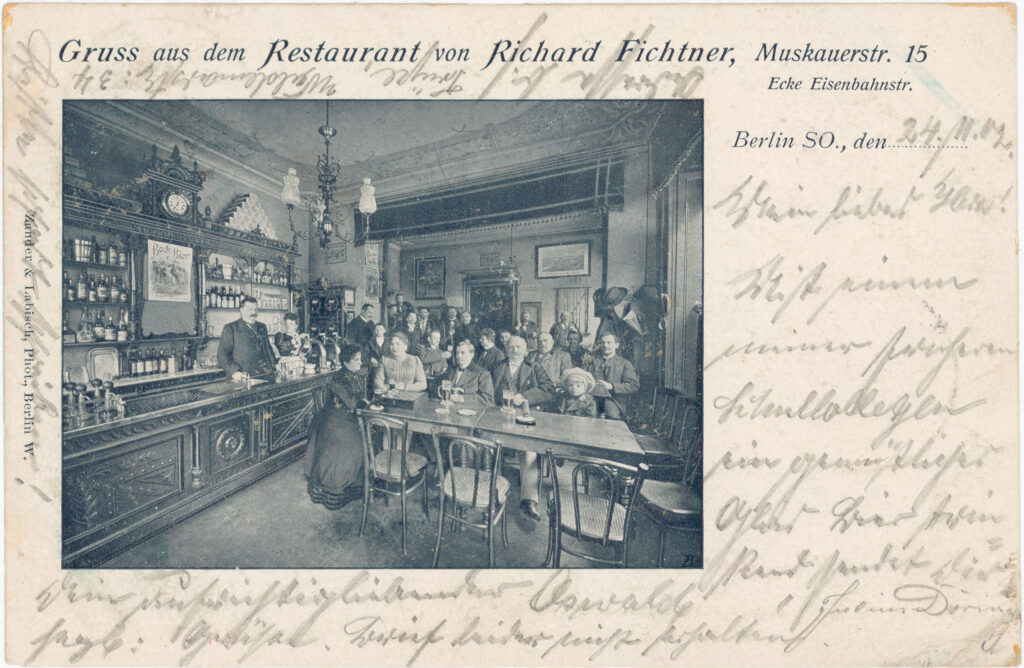

Berlin had a permissive queer scene at the beginning of the 20th century. Despite state discrimination, such as Paragraph 175, which criminalized sexual contact between men, there were opportunities not only in high society, but for the entire Berlin population to meet other gays, lesbians and trans people. Although there was no relevant paragraph for lesbian women, they experienced multiple discrimination and ostracism for their sexuality and gender. There was little censorship in the Weimar Republic, although Paragraph 184 was used to combat “lewd” writings. Nevertheless, at least six lesbian magazines were published in Berlin, including the well-known magazine “Die Freundin”. So-called clubs were meeting places for lesbian women. Here they found a community that was otherwise often denied to them in society and were able to develop freely, such as in the ladies’ club “Erâto” at Kommandantenstr. 72. One of the largest clubs was the “Violetta” at Hasenheide 52-53 from 1926 to 1935. It was run by Charlotte “Lotte” Hahm (1890-1967), a prominent figure in the lesbian scene, who was active in activism together with Käthe Fleischmann, née Reinhardt. From 1933, meeting places of the homosexual movement were monitored or even banned: in 1935, the “Violetta” had to close due to denunciation. The Peter Plewka collection contains images of the clubs, but they are not recognizable as lesbian places. Knowledge about them and their social significance for lesbian life increasingly disappeared from the collective memory with the death of those involved.

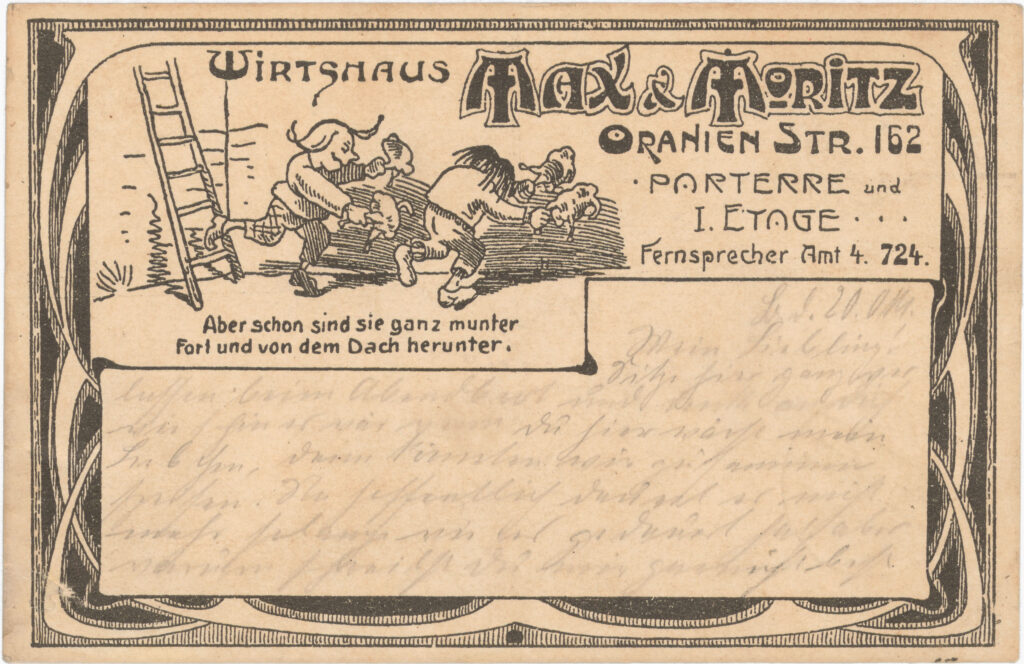

In 1945, Lotte Hahm reopened a lesbian bar with Kati Reinhardt on Spittelmarkt in East Berlin and later moved to “Max & Moritz” at Oranienstr. 162, which remained a meeting place for the lesbian scene until the 1960s. The “Max & Moritz” was founded in 1902 as a pub and had one of the best locations on the “Boulevard of the East” until the 1930s.

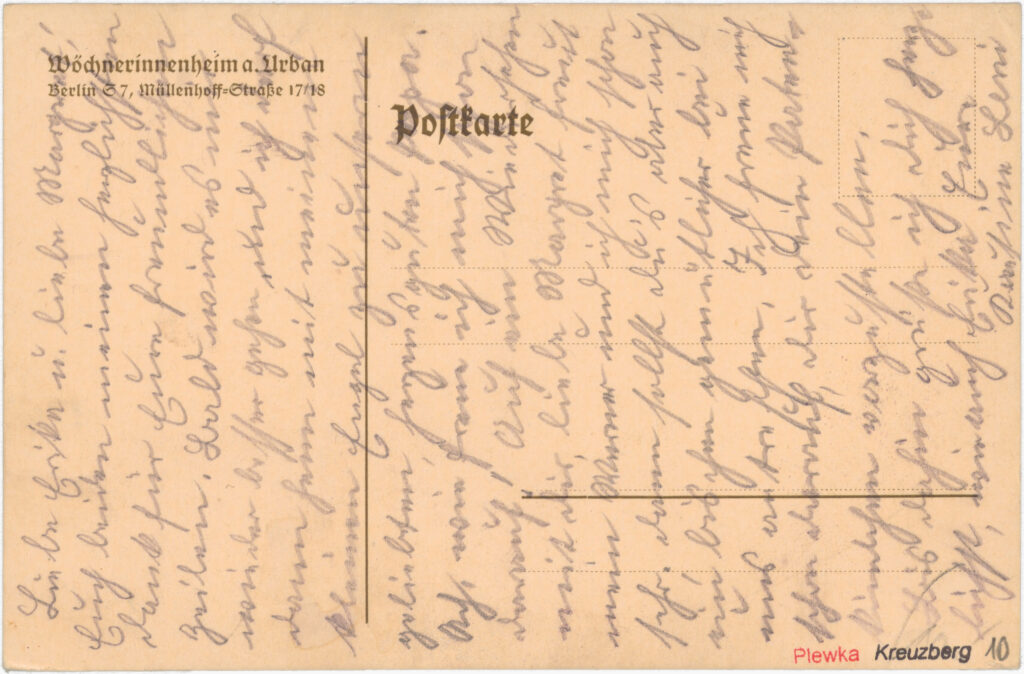

Maternity home Am Urban

Until 1912, the maternity home Am Urban was the only one of its kind in Berlin. The term “maternity home” refers to women who have recently given birth and are in the postpartum period. Founded in the 18th century, maternity homes were specialized institutions for the care of women and newborns during childbirth and in the first weeks afterward; midwives were trained at the Charité in Berlin from 1751.

Home births were common until around the middle of the 20th century, partly for fear of the high costs of a doctor or hospital. In the 19th century, however, one in six women giving birth died in childbirth due to a lack of hygiene and medical care.

The maternity home Am Urban in Kreuzberg offered “impecunious” mothers and their newborns the necessary care that they did not have at home. Postcards from the Peter Plewka collection contain references to the maternity home Am Urban. While the photographic motif depicts the staff and the building orderly, the drawn motif conveys an idyllic, romanticized idealization of childbirth.

A maternity home was run in the Am Urban building at Müllenhoffstr. 17/18 from 1897. It was a private non-profit institution until 1945, after which it became part of a municipal hospital.

The Working Woman

Until 1900, women in Prussia were not considered legally competent and were under the guardianship of their fathers or husbands. However, women from the lower classes had always worked, and employment before marriage was common. Women worked, for example, as maids, laundresses, or home-based workers. In factories, they were often paid only half the wages of men, despite doing comparable work, as they were considered supplementary earners.

From the 1860s onward, various women’s movements emerged and organized themselves into associations, such as the “Association for Women and Girls of the Working Class to Promote Knowledge and Foster Sociability,” founded in what is now Kreuzberg. These associations fought for equal pay, the right to independence, voting rights, and education.

Around the turn of the century, the employment rate of women increased from 24.6 percent (in 1895) to 35.3 percent (in 1925). However, from 1900 to 1958, a wife was only allowed to work if she could also fulfill her household duties, according to Paragraph 1356 of the Civil Code. As a result, a wife needed her husband’s permission to be able to work.

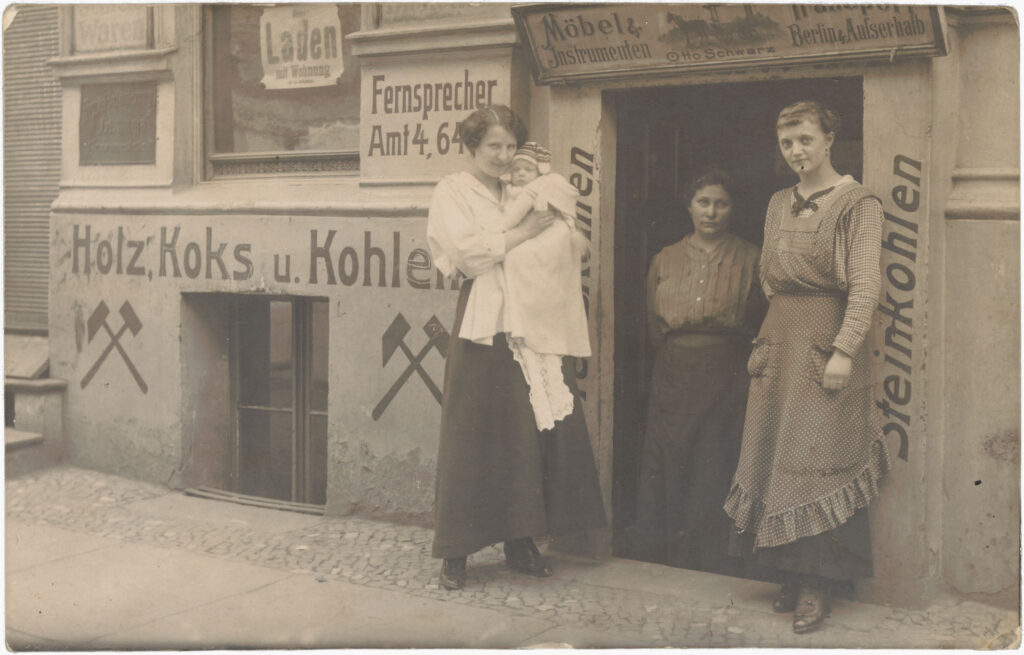

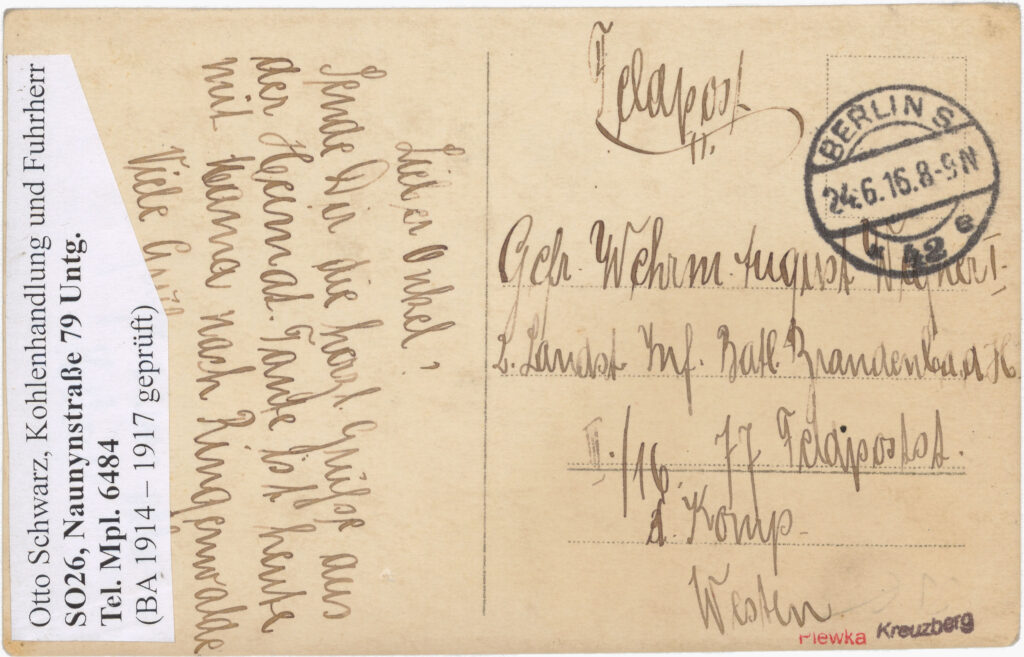

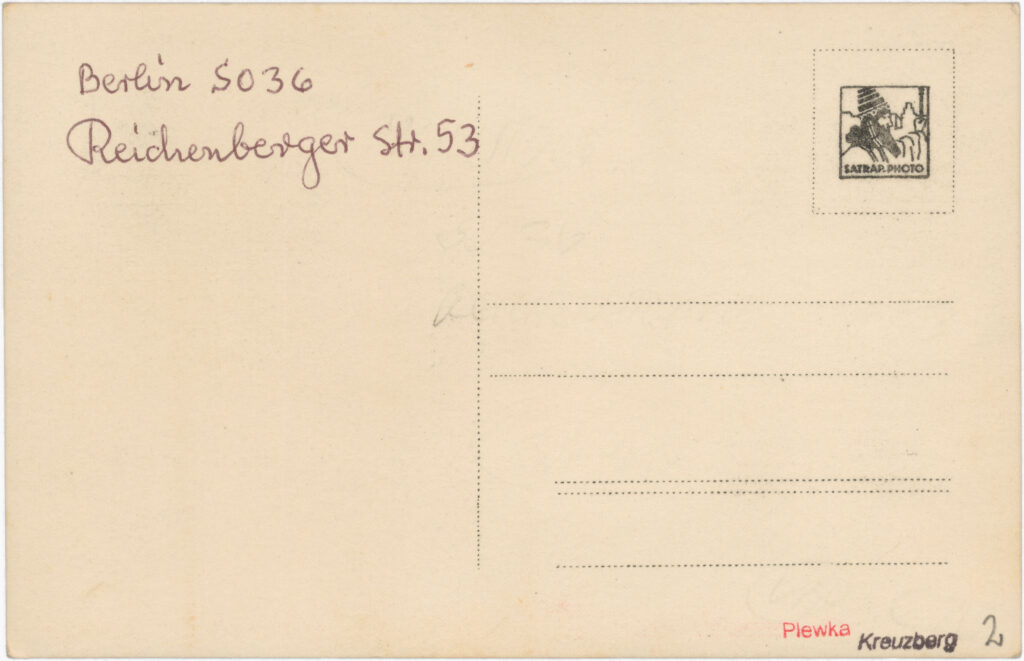

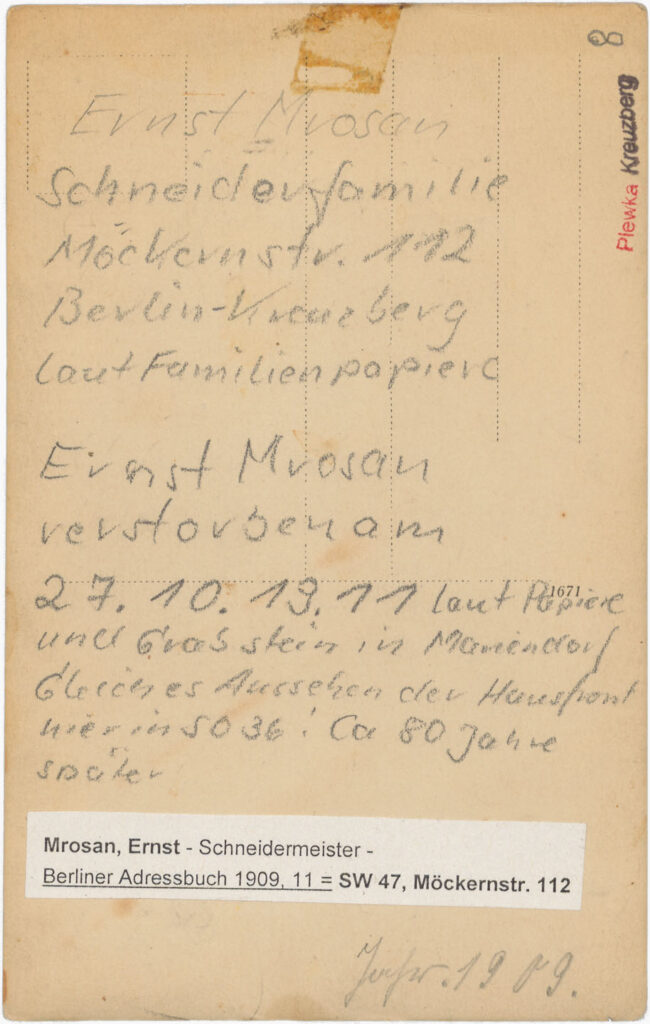

In the postcard collection of Peter Plewka, women are depicted in their professional lives: serving drinks, as shop owners on signage, with their children and husbands, or individually in front of their businesses.

In Peter Plewka’s collection, there are several examples of women in the workforce in Kreuzberg at the beginning of the 20th century. They can be recognized by their uniforms as employees. The names of female shop owners are clearly displayed on the shop signs depicted. There are also family businesses where the family poses with employees in front of their shops. From today’s perspective, these images are not unusual. However, for the time around 1900, they are particularly remarkable given the legal and societal restrictions placed on women, as they demonstrate how women managed to assert themselves in the workforce despite the challenges.

Author

Kathrin Schwarz

LITERATURE

Further reading:

Andrea Bergler. Von Armenpflegern und Fürsorgeschwestern: kommunale Wohlfahrtspflege und Geschlechterpolitik in Berlin und Charlottenburg 1890 bis 1914. Franz Steiner Verlag, 2011.

Jana Haase (2024). Die Lette-Schwestern. Eine biografische Zeitreise, in: Digitales Deutsches Frauenarchiv

URL: https://www.digitales-deutsches-frauenarchiv.de/themen/die-lette-schwestern-eine-biografische-zeitreise

Zuletzt besucht am: 07.07.2024

Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Berlin. Die Hälfte Berlins – Ein Blick auf 150 Jahre Frauenbewegung. Open-Air-Ausstellung, März 2022. In: https://digital.zlb.de/viewer/metadata/34430084/1/-/

Adelheid Popp. Die Arbeiterin im Kampf um’s Dasein. Verlag der Wiener Volksbuchhandlung, I. Band, 1895.

Kena Stüwe. „Ein Merkstein der Berliner Frauenbewegung” – Die Gründung des “Vereins für Frauen und Mädchen der Arbeiterklasse”. FEShistory. Blogeintrag vom 24.01.2024. In: https://www.fes.de/feshistory/blog/berliner-frauenbewegung

References for „Invisible: Lesbian clubs and meeting places”:

Max und Moritz Berlin. Offizielle Homepage. Historie. In: https://maxundmoritzberlin.de/1940-bis-2006/

Ingeborg Boxhammer; Christiane Leidinger (2024). Lotte Hahm, in: Digitales Deutsches Frauenarchiv

URL: https://www.digitales-deutsches-frauenarchiv.de/akteurinnen/lotte-hahm

Zuletzt besucht am: 07.07.2024

Ingeborg Boxhammer; Christiane Leidinger. Die Szenegröße und Aktivistin Lotte Hahm. In: Stella Hindemith, Christiane Leidinger, Heike Radvan, Julia Roßhart (Hg.): Wir* hier! Lesbisch, schwul und trans* zwischen Hiddensee und Ludwigslust – Ein Lesebuch zu Geschichte, Gegenwart und Region. Lola für Demokratie in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern e. V., Berlin 2019. S. 20 UND S. 57–59. In: https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Lesebuch_Wir_hier.pdf

Ingeborg Boxhammer; Christiane Leidinger (2021). Offensiv – strategisch – (frauen)emanzipiert: Spuren der Berliner Subkulturaktivistin* Lotte Hahm (1890-1967). GENDER – Zeitschrift für Geschlecht, Kultur und Gesellschaft, 13(1), 91-108.

In:https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/72151/ssoar-gender-2021-1-boxhammer_et_al-Offensiv_-_strategisch_-_frauenemanzipiert.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&lnkname=ssoar-gender-2021-1-boxhammer_et_al-Offensiv_-_strategisch_-_frauenemanzipiert.pdf

Jens Dobler. Von anderen Ufern: Geschichte der Berliner Lesben und Schwulen in Kreuzberg und Friedrichshain. Gmünder 2003.

Adele Meyer (1994). Lila Nächte. Die Damenklubs in Berlin der 20er Jahre. Zitronenpresse.

Christiane Leidinger. LSBTI-Geschichte entdecken! Leitfaden für Archive und Bibliotheken zur Geschichte von Lesben, Schwulen, Bisexuellen, trans- und intergeschlechtlichen Menschen. Wege zur Identifizierung und Nutzung von relevanten Quellenbeständen Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts bis Anfang der 1970er Jahre. Hg. von der Senatsverwaltung für Justiz, Verbraucherschutz und Antidiskriminierung, Berlin 2017, S. 23, Zugriff am 23.11.2020 unter https://www.berlin.de/sen/justva/presse/pressemitteilungen/2017/pressemitteilung.645784.php.

Heike Schader (2004). Virile, Vamps und wilde Veilchen. Sexualität, Begehren und Erotik in den Zeitschriften homosexueller Frauen im Berlin der 1920er Jahre. Ulrike Helmer Verlag.

References for „Maternity home Am Urban”:

Quelle: DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1205275

DMW – Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 1897; 23(50): 808

Link: https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0029-1205275

Berliner Adreßbücher. Digitale Landesbibliothek Berlin.

Literatur:

Sherwin B. Nuland. Ignaz Semmelweis. Arzt und großer Entdecker. Piper Verlag, München 2006.

Rainer Pöppinghege. Zwischen Hausgeburt und Hospital. Zur Geschichte der Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. Schmitz u. Söhne, Wickede 2005.

Daniel Schäfer. Geburtshilfe. In: Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005. S. 463–464.

Yvonne Schwittai. Zur Geschichte der Frauenkliniken der Charité in Berlin von 1710 bis 1989 unter besonderer Berücksichtigung baulicher und struktureller

Entwicklungen. Medizinischen Fakultät

Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 2012. S. 30. In: https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/fub188/13748/Promotion_Fassung_Bibliothek.pdf;jsessionid=27A915537FC2DC87AB583FEC7552FDFF?sequence=1

Urte Verlohren. Krankenhäuser in Groß-Berlin. Die Entwicklung der Berliner Krankenhauslandschaft zwischen 1920 und 1939. BeBra Verlag. Berlin 2019. S. 327.

References for „The Working Woman”:

Gesetzestexte des Bürgerlichen Gesetzbuches (BGB in unterschiedlichen Fassungen):

https://lexetius.com/BGB/1356#2

Stefan Bajohr. Die Hälfte der Fabrik. Geschichte der Frauenarbeit in Deutschland 1914 bis 1945, 2. Aufl., Marburg 1984.

Ute Gerhard (Hg.). Frauen in der Geschichte des Rechts. Von der Frühen Neuzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1997.

Dr. Barbara von Hindenburg (2024). Erwerbstätigkeit von Frauen im Kaiserreich und in der Weimarer Republik, in: Digitales Deutsches Frauenarchiv

URL: https://www.digitales-deutsches-frauenarchiv.de/themen/erwerbstaetigkeit-von-frauen-im-kaiserreich-und-der-weimarer-republik

Zuletzt besucht am: 07.07.2024

Angelika Schaser. Frauenbewegung in Deutschland 1848-1933. Herder Verlag, Freiburg 2020.

Ulla Wikandera. Von der Magd zur Angestellten. Macht, Geschlecht und Arbeitsteilung 1789–1950, Frankfurt a. M. 1998.