- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

WHERE ARE THE QUEERS AT?!

Queer in the Weimar Republic

“If one wished to produce a vast portrait of a world-class city like Berlin, penetrating the depths rather than merely dwelling on the surface, one could scarcely ignore the impact of homosexuality, which has fundamentally influenced both the shading of this picture in detail and the character of the whole.”

Hirschfeld, Magnus, Berlin’s Third Sex, translated by James J. Conway, Berlin 2017, p. 15.

The lives of queer people, particularly queer men, were politically shaped by Section 175 of the Penal Code in the Weimar Republic. This section, introduced during the Kaiserreich, criminalized sexual contact between two men. It was frequently amended in the following years and only finally abolished in the Federal Republic in 1994.

Although the Weimar Republic adopted Section 175, the founding of the Republic was a moment of hope for the queer population. The rigid norms of society broke down after the war, and the queer community hoped to benefit from this change. For this reason, the (organized) networking of queer people increased significantly at that time. They founded associations and began to actively advocate for the recognition and decriminalization of queerness.

Terms like “queer” and “homosexual” were not common during the Weimar Republic. Instead, terms like “Urning” (for males) and “Urninde” (for females) were used. Terms like “friends” were also frequently used. Therefore, when the following texts refer to “queer,” it is not a term from that era but a contemporary term. It is used in the text to describe sexuality and gender identities that deviate from the norms of that time. Furthermore, the term is connected to political struggles against the binary and heterosexual norm.

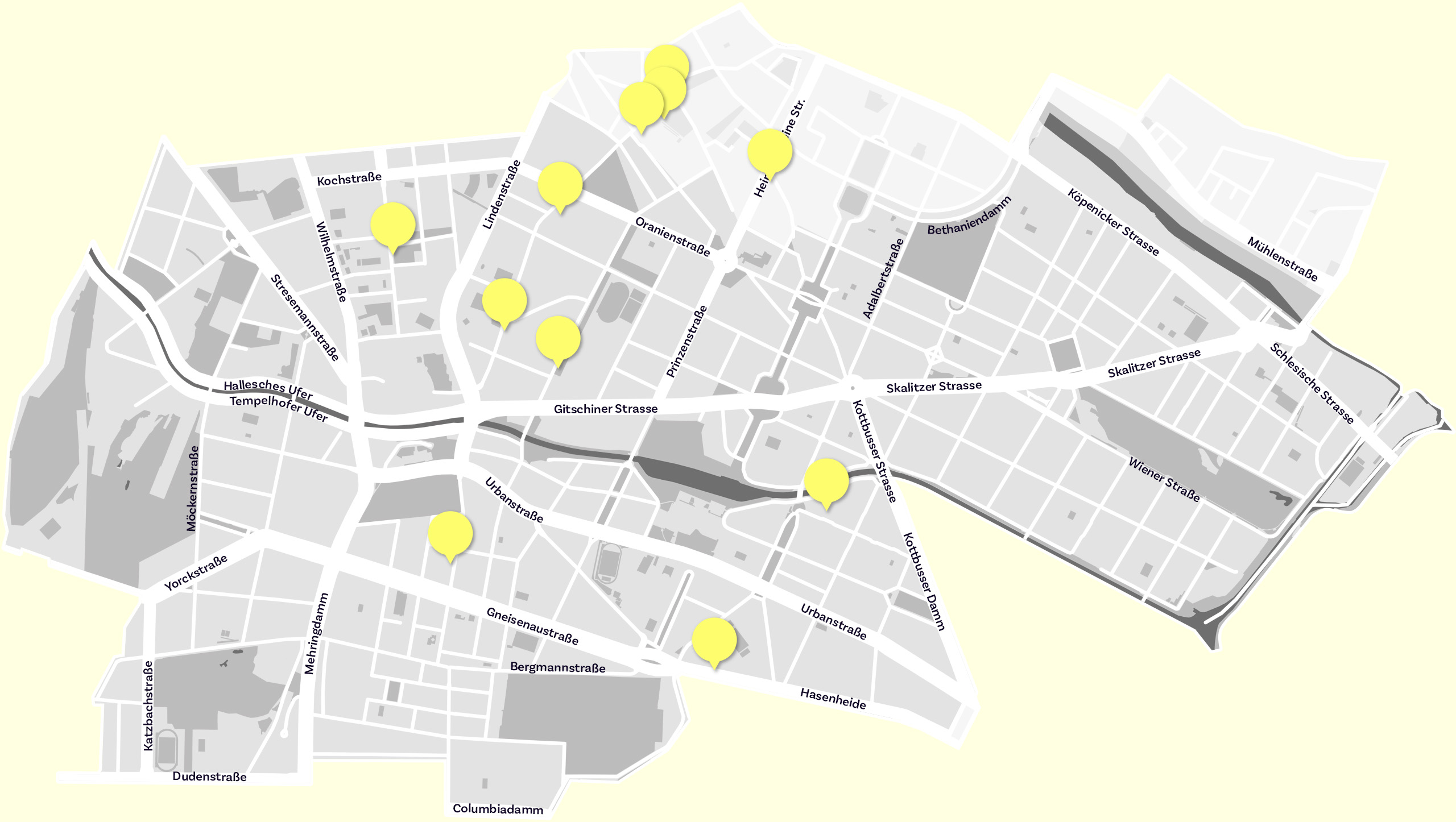

The following will examine various places of queer life in Kreuzberg. Research shows that there were many venues, association headquarters, and publishing houses of queer people, and that postcards depicting queer life exist. However, the postcard collection of Peter Plewka contains few images of this. To address this gap and follow the few traces found in the collection, postcards showing the surroundings of these places, rather than the places themselves, will also be used.

"Fighting spirit must fill your hearts and shine from your eyes." - Associations and Organizations

As the Weimar Republic became established, queer individuals founded numerous associations and groups. From 1919 onwards, so-called friendship associations emerged in many German cities where queer people met. These gatherings were focused on entertainment and networking, but also on political activism. In the following years, newly founded associations often cited the unfulfilled hopes for the swift abolition of Section 175, which criminalized sexual contacts between men, as a reason for their activity.

Deutscher Freundschafts-Verband

At Alexandrinenstraße 8, the Karl-Schultz-Verlag was located, which provided space for the ‘Deutscher Freundschafts-Verband’ (DFV). From at least 1919, the DFV was the umbrella organization for many queer associations nationwide. The main goal of the DFV was the “liberation of all inverts from legal and social disgrace”(own transl.) — a demand that was deliberately broader than “just” the abolition of Section 175. Their statutes further stated: “An organization that wants to be taken seriously does not have the task of promoting ‘naked culture’ (tactical considerations already prohibit that). It must strive to include as many well-disposed inverts as possible and ensure justice for them (…)” (own transl.). The printing house of the publisher printed their magazine ‘Die Freundschaft’. In May 1920, the association moved to Planufer 5, where a queer venue became its new home.

BUND FÜR MENSCHENRECHT

In September 1919, the ‘Berliner Freundschaftsbund’ was founded as a subsection of the ‘Deutscher Freundschafts-Verband’ (DFV). The ‘Berliner Bund’ met at the garden house at Alte Jakobstraße 89. Three years later, it merged with the ‘Vereinigung der Freunde und Freundinnen’, which met in the ballroom of the Central-Festsäle at Alte Jakobstraße 32, and was renamed the ‘Bund für Menschenrecht’ (BfM). Between 1922 and 1923, the BfM met at the City-Festsäle at Dresdener Straße 52/53, then moved back to Alte Jakobstraße. According to its own statements, the BfM had up to 48,000 members at times and, unlike other associations, did not only address the educated bourgeoisie. The BfM’s goals included the abolition of Section 175 and the fight against the social ostracism of homosexuals. This was similar to the DFV, whose significance and function the BfM later took over.

A particular feature of the association was the continuous presence of female voices. Many associations at the time focused on male homosexuality and had few female members. Although equality of the sexes cannot be said to have been achieved at the BfM, there was always a woman on the board from 1922 onwards.

In 1934, due to a lack of members, the dissolution of the BfM was requested. Many had presumably left the association out of fear of consequences from the National Socialists.

„Not only dance and social events can bring you equality, but also struggle is necessary if you want respect and esteem. Fighting spirit must fill your hearts and shine from your eyes. Therefore, organize yourselves in the ‘Bund für ideale Frauenfreundschaft’.“

Hahm, Lotte / Radszuweit, Friedrich: Aufruf an alle gleichgeschlechtlich liebenden Frauen, in: Die Freundin, 1930, No. 22, own transl.

DAMENCLUB VIOLETTA

Shortly after Lotte Hahm moved to Berlin, she founded the ‘Damenclub Violetta’ in 1926. It became one of the largest lesbian clubs in the city. The club, which was also part of the DFV and later the BfM, had at times up to 400 members. Their focus was on networking and correspondence, as well as political activism. They also published the magazine ‘Die Freundin’. The target audience of the club and its magazine were primarily lesbians, but events were also organized for “transvestites”; this outdated term referred to individuals who dressed contrary to the dress code of their assigned sex. The club’s focus was aligned with Lotte’s personal engagement, as Lotte was actively involved in this scene and often appeared in traditionally male clothing.

The ‘Damenclub Violetta’ was dissolved under the National Socialists; however, Lotte Hahm continued to engage for lesbians and “transvestites.” There is disagreement in research about a possible incarceration due to this activism. Lotte Hahm survived National Socialism and remained an activist until her death in 1967.

Dancing until Dawn - Urning Balls

From October to Easter, Urning Balls filled the nights. They were known for their extravagance and excess. The target audience of these balls were queer people, whose existence was stigmatized in society, but whose balls were considered top-notch entertainment. Besides queer people, a crowd of interested parties and reporters also attended, ensuring that the spectacles were covered in newspapers and conversations the next day.

Several times a week, Berliners and tourists flocked to the Urning Balls, of which sometimes several ones were happening in one evening. They emerged around 1900 and played a significant role in the lives of the queer population in Berlin. Here, queer people could coexist and live out their sexuality. There was also space for playing with gender representation and cross-dressing — a way of expressing oneself and gender identity that could not otherwise be publicly presented.

Urning Balls had primarily two goals: They aimed to make queer people acquainted with each other and to create the illusion of a sexually and gender-liberated society for one evening. However, this always happened under the watchful eyes of the police, who stationed male officers (women were first allowed to serve in Cologne in 1923) at the balls.

Until 1907, Urning balls retained their relevance within the queer community; then they were officially banned following a socio-political scandal in the vicinity of the Kaiser (Eulenburg Affair). In the 1920s, the balls experienced a resurgence before being banned again in 1933.

„The group in the most colorful and dazzling array presents an extremely peculiar and attractive image. First, the festival participants strengthen themselves at tables adorned with flowers. The leader, in a lively velvet jacket, welcomes the guests with a brief and hearty speech. Then, the tables are cleared away. The ‘Danube Waves’ are played, and accompanied by cheerful dance tunes, couples swing through the night in a circle. From the side rooms, one hears bright laughter, clinking glasses, and lively singing, but nowhere—no matter where one looks—are the boundaries of a costume party of a more refined kind crossed. No discordant note mars the general joy until the last participants leave, in the dim light of the cold February morning, the place where they had been allowed to dream for a few hours among like-minded individuals as who they are inwardly.“

Hirschfeld, Magnus, Berlins drittes Geschlecht, pp. 56-57, own transl.

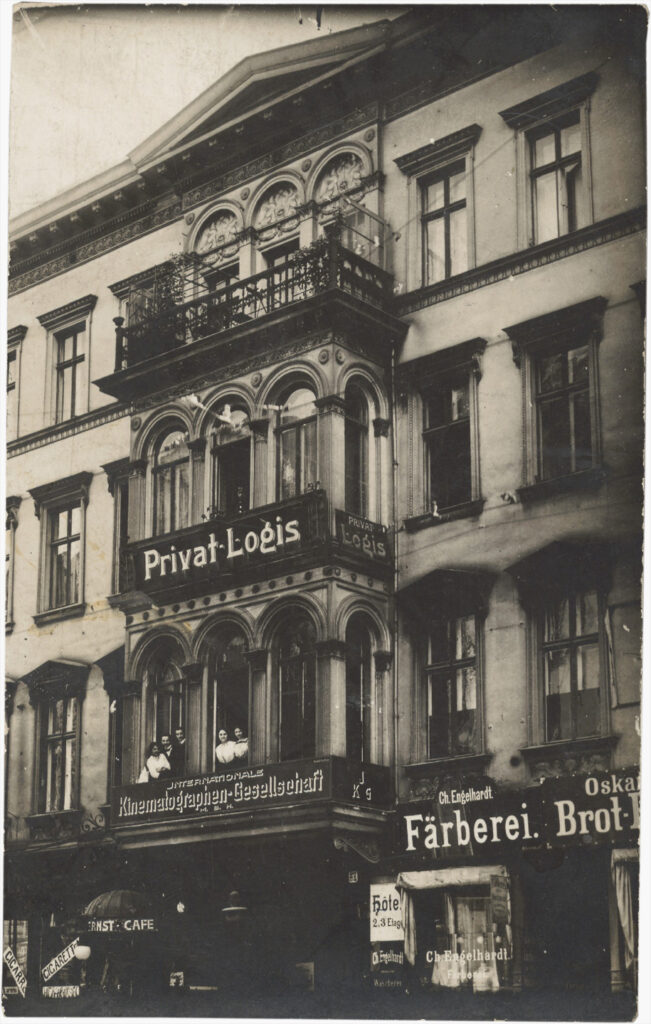

CENTRAL-FESTSÄLE

In winter, the Central Festsäle opened its doors several times a week for visitors to the Urning Balls, which suspended a multitude of social norms and constraints for an evening.

CITY-FESTSÄLE

The ‘Bund für Menschenrecht’ also regularly organized balls where queer individuals could meet and spend their evenings. These took place in the City Festsäle, located just a few house numbers away from the business shown on the postcard.

Pub, Casino, Cabaret –

Queer Entertainment Culture

Both then and now, Kreuzberg was an area with an active nightlife — also for queer individuals.

Besides the classic bars existing independently of their surroundings, there were venues with queer audiences near barracks, catering to the stationed soldiers. However, they often had a very short lifespan as they were quickly closed by the military once the authorities became aware of their existence.

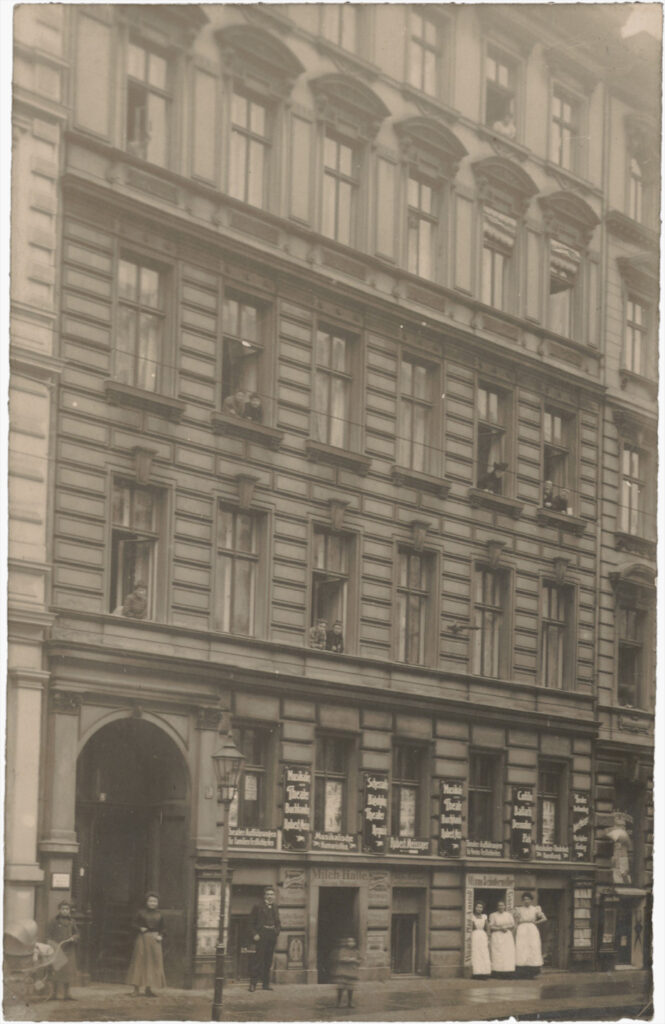

THE ALTE JAKOBSTRASSE

For many years, Alte Jakobstraße served as a queer entertainment mile. Various buildings offered a diverse range of bars and pubs.

49 – Restaurant (Name Unknown)

At Alte Jakobstraße 49, just a few meters from the entrance of the business shown here, one of the co-founders of the ‘Berliner Freundschaftsbund’ and later board member of the ‘Bund für Menschenrecht’ ran his establishment and provided space for “solid, middle-class gentlemen.” Urning Balls were also held here.

60 – Eldorado-Diele

A few houses further at number 60 was a queer venue described as a “cozy home for older gentlemen.” This highlights that, both then and now, older people were also part of the queer community and participated in it.

Hirschfeld, Magnus, “Berlins drittes Geschlecht”, p. 37, own transl.

174 – Cabarett ‘Spinne’

A few house numbers away from the building depicted here was the Cabaret ‘Spinne’, a popular destination for Berlin’s queer population. It presented a variety of performances, including ones where performers played with gender.

“It was heated by a big old-fashioned iron stove. Partly because of the great heat of this stove, partly because they knew it excited their clients (die Stubben), the boys stripped off their sweaters or leather jackets and sat around with their shirts unbuttoned to the navel and their sleeves rolled up to the armpits.”

Christopher Isherwood: “Christopher and His Kind”, Suffolk 1977, p. 30.

‘Noster’s Restaurant zur Hütte’

‘Noster’s Restaurant zur Hütte’ catered to a male audience and was located in the working-class district of Kreuzberg.

‘BÜRGER CASINO’

The ‘Bürger Casino’ was also a place of queer life in Kreuzberg from the mid-1920s onwards. (The exact location of the ‘Bürger Casino’ is disputed; it is sometimes located in Friedrichsgracht.)

“For Enlightenment and Intellectual Elevation of Ideal Friendship” - The Magazine Scene

The queer magazine scene flourished at the beginning of the 20th century. In close connection with friendship associations, a number of publications emerged that specifically addressed a queer (primarily homosexual) audience. The magazines served as mouthpieces for clubs and associations and included political statements and demands, as well as entertainment and texts from the community. Furthermore, the magazines contributed to networking by publishing advertisements and providing information about events.

DIE FREUNDSCHAFT

One of the most prominent magazines was initially printed and published at Alexandrinenstraße 8 and later at Planufer 5. On August 14, 1919, the Karl-Schultz-Verlag published the first edition of ‘Die Freundschaft – Wochenschrift für Aufklärung und geistige Hebung der idealen Freundschaft’ (Weekly Magazine for Enlightenment and Intellectual Elevation of Ideal Friendship, own transl.) The first edition consisted of 20,000 copies, and the editors stated their goals:

„Die Freundschaft

■■ aims to be an enlightening, instructive, and entertaining good friend and advisor in all life situations for all free-thinking friends.

■■ aims to represent the interests of free-thinking single persons in every way. It wants to act as a mediator for those whose desired ideal friendship is hindered by economic circumstances or other reasons.

■■ supports the viewpoint of free self-determination and control of the adult individual over themselves.

■■ does not want to be a scandal or sensational paper, but rather a magazine built on ideal foundations, keeping up with the times, enlightening, and free-thinking.” (Was wir wollen!, in; Die Freundschaft No. 1, [August] 1919, p. 1, own transl.)

The second issue included an article on the defamation of homosexual individuals in the press and the need for “true enlightenment.” Thus, the magazine’s main goals were laid out, which largely aligned with those of the “homosexual movement” in the Weimar Republic: the abolition of §175 and the enlightenment about homosexuality. Additionally, the magazine aimed to provide entertainment and support for homosexual people. Unlike some other magazines, ‘Die Freundschaft’ targeted the general public rather than just the educated bourgeoisie. The magazine could be purchased at kiosks and from street vendors, further facilitating access.

'DIE FREUNDIN'

‘Die Freundin’ was the first well-known lesbian magazine in the German-speaking world and was also the longest-lasting during the Weimar Republic. In 1924, the ‘Damen Club Violetta’ published its club magazine ‘Die Freundin’ for the first time, and its publication continued until the club’s dissolution in 1933. During this time, the magazine was firmly established in the lesbian scene. It took political stances, informed about lesbian life, published short stories and novels, advertisements for meeting places, and personal ads. It primarily addressed lesbian individuals, but due to the club’s orientation, it also included offerings for “transvestites.” An exception was the advertisement section, where gay men and heterosexual individuals could also be found. Especially in the case of the often politically tinged editorials, the authors were frequently men.

Later research revealed that many queer women of the time attribute the development of a collective lesbian identity to the magazine ‘Die Freundin’, as it connected lesbians nationwide.

Author

Janika Stolt

MA Public History

LITERATURE

Beachy, Robert: Gay Berlin. Birthplace of a Modern Identity. New York 2014. Knopf Verlag.

Bollé, Michael: Eldorado: homosexuelle Frauen und Männer in Berlin 1850 – 1950; Geschichte, Alltag und Kultur ; [Ausstellung im Berlin-Museum: 26. Mai – 8. Juli 1984]. Berlin 1992. Frölich & Kaufmann.

Digitales Deutsches Frauenarchiv (Hg.): Über Lotte Hahm, https://www.digitales-deutsches-frauenarchiv.de/akteurinnen/lotte-hahm#actor-network.

Dobler, Jens: Von anderen Ufern – Geschichte der Berliner Lesben und Schwulen in Kreuzberg und Friedrichshain. Berlin 2003. Bruno Gmünder Verlag.

Experiencing History (Hg.): Advertisement for “Violetta Ladies Club”, https://perspectives.ushmm.org/item/advertisement-for-violetta-ladies-club#.

Gammerl, Benno: Queer. Eine deutsche Geschichte vom Kaiserreich bis heute. München 2023. Carl Hanser Verlag.

Hindermith, Stella/Leidinger, Christiane/Radvan, Heike/Roßhart, Julia (Hg.). Wir* hier! Lesbisch, schwul und trans* zwischen Hiddensee und Ludwigslust. Ein Lesebuch zu Geschichte, Gegenwart und Region. Berlin 2019. Lola für Demokratie in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern e.V..

Hirschfeld, Magnus, Berlins Drittes Geschlecht. Berlin 1904. Verlag rosa Winkel.

Lesbengeschichte(Hg.): Lotte (Charlotte) Hahm (1890-1967), https://lesbengeschichte.org/bio_hahm_d.html.

Lücke, Martin: Komplizen und Klienten. Die Männlichkeitsrhetorik der Homosexuellen- Bewegung in der Weimarer Republik als hegemoniale Herrschaftspraktik. In: Brunotte, Ulrike/Herrn, Rainer (Hg.): Männlichkeiten und Moderne. Geschlecht in den Wissenskulturen um 1900, Bielefeld 2007. Transcript. S. 97-110.

Micheler, Stefan: Zeitschriften, Verbände und Lokale gleichgeschlechtlich begehrender Menschen in der Weimarer Republik. Online-Publikation 2008. http://www.stefanmicheler.de/wissenschaft/stm_zvlggbm.pdf.

Moreck, Curt: Ein Führer durch das lasterhafte Berlin. Das deutsche Babylon 1931. München 2020 (Erstausgabe 1931). Btb.

Schader, Heike: Virile, Vamps und wilde Veilchen. Sexualität, Begehren und Erotik in den Zeitschriften homosexueller Frauen im Berlin der 1920er Jahre, Berlin 2004. Ulrike Helmler Verlag.