- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

Kreuzberg Garrison

Until today, there are grand and spacious streets in Berlin such as Kurfürstendamm, Friedrichstraße, and Mehringdamm, which were originally built for military purposes. The roads leading out to the west and south were laid out under King Friedrich Wilhelm I (1688 – 1749) and served as access routes to the maneuver grounds outside the city for the soldiers stationed in Berlin. The troops marched to Grunewald, Döberitz, and Tempelhofer Feld to practice combat. Since the long march routes were very arduous, planning and construction of barracks closer to the training grounds began in the mid to late 19th century.

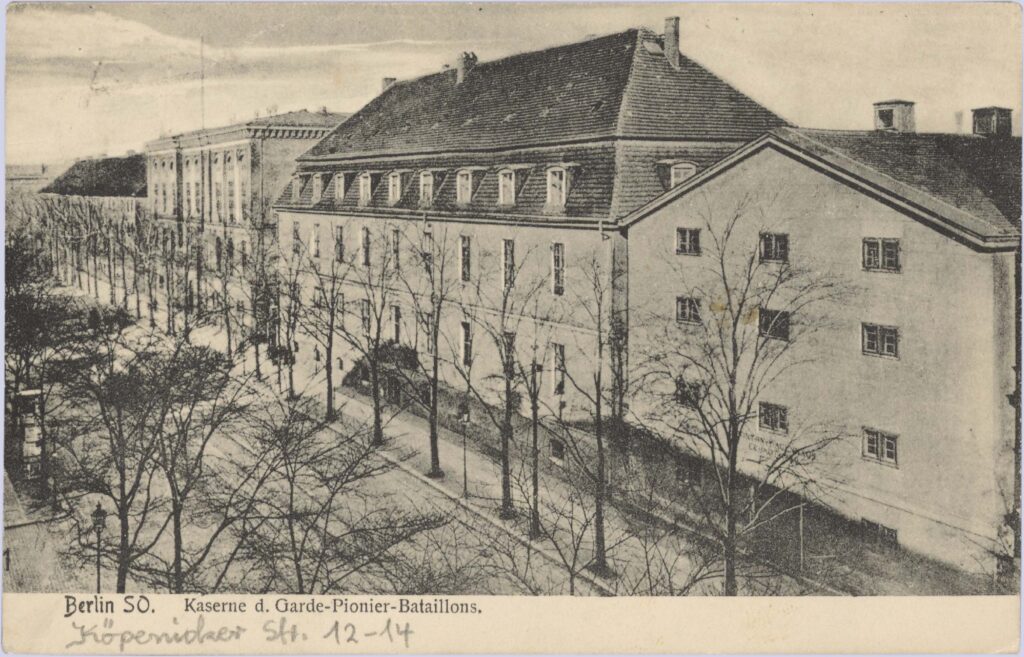

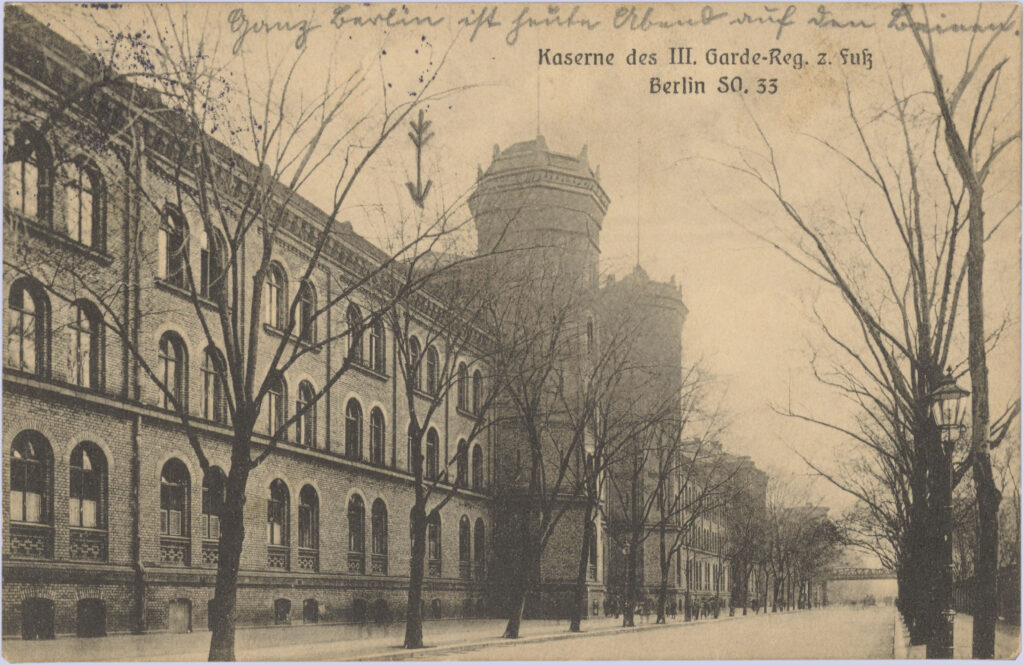

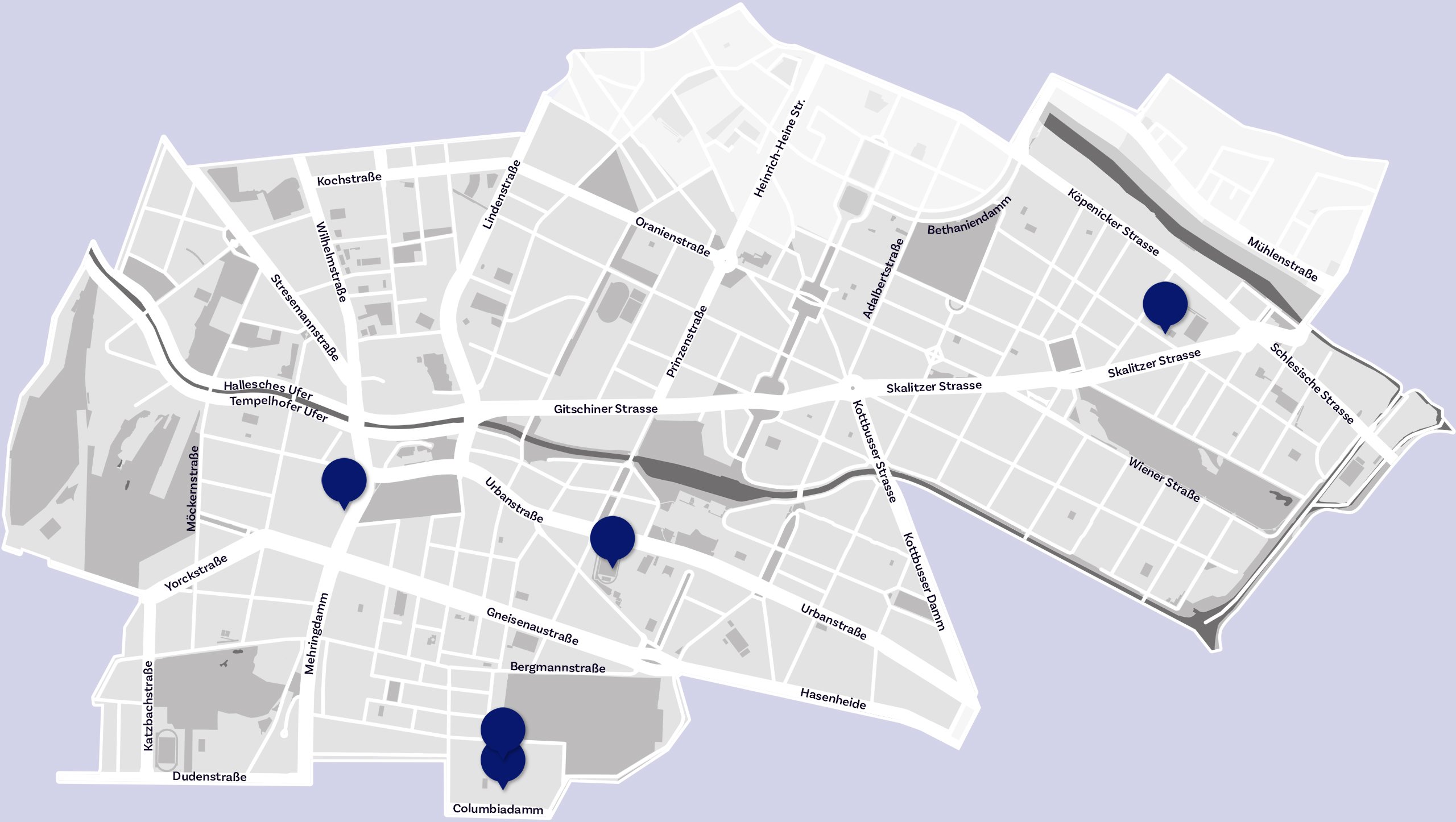

Thus, new accommodations for soldiers were built in Kreuzberg, which was still partially undeveloped. By 1900, five out of thirteen Berlin regiments had their barracks in Kreuzberg. In addition to the usual buildings for accommodation, these also included buildings for military administration and supply, such as a garrison bakery. Simultaneously to the construction of the barracks, the population in Berlin increased rapidly, and the city expanded further. As a result, the barracks were located in inhabited areas by the turn of the century at the latest.

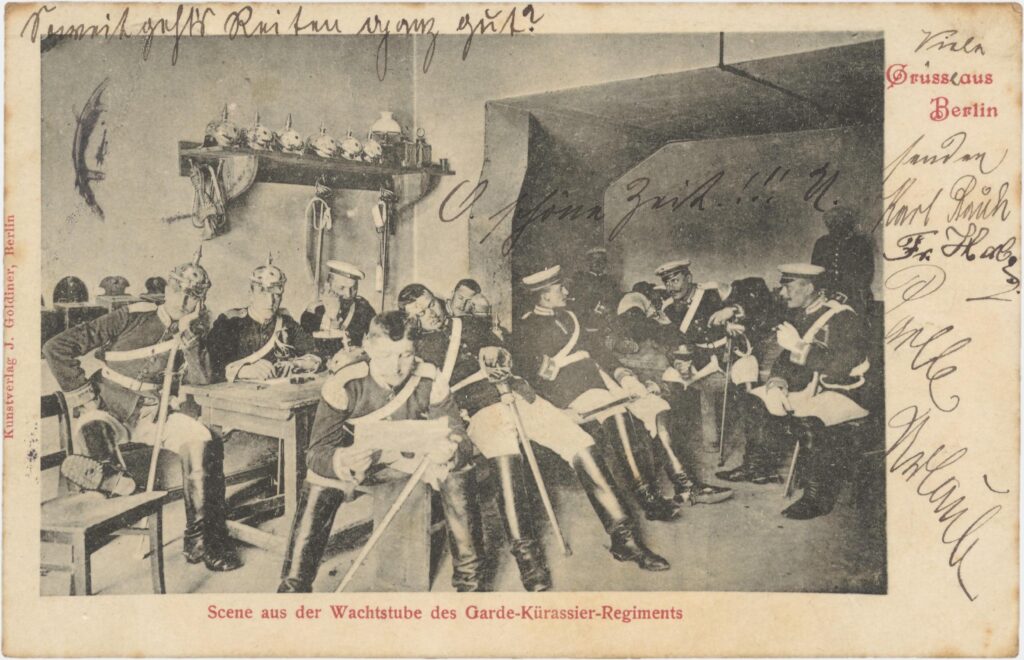

Peter Plewka’s collection contains numerous views of barracks, armament factories, and parades in Kreuzberg, thus depicting everyday life in a district shaped by the military. The partially staged photographic motifs of the postcards offer an insightful look into a nearly forgotten and yet formative part of Kreuzberg’s history. However, they also raise the question which aspects of the coexistence of civilians and soldiers were not depicted.

Soldiers as Guests

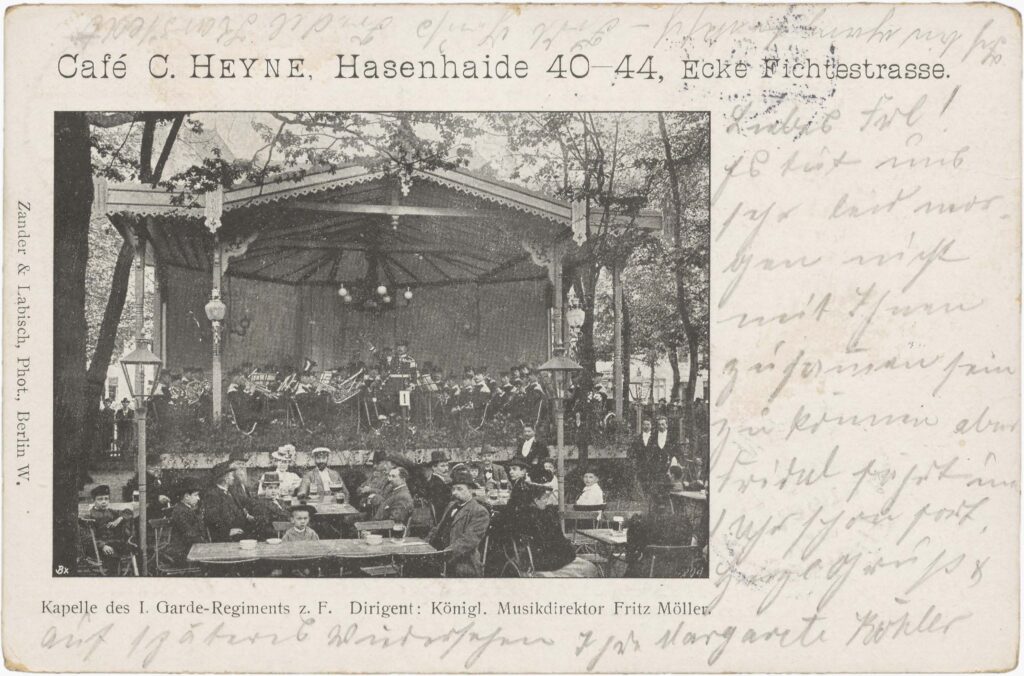

The military was part of everyday life in Kreuzberg pubs, cafés, and beer gardens. Performances by military bands in Hasenheide were a popular entertainment for many Berliners. Moreover, uniformed soldiers frequented Kreuzberg establishments, mingling with civilians. However, soldiers were explicitly forbidden to visit social democratic establishments, meeting places, and events.

A fixed part of the soldiers’ everyday life were those establishments that often had clear military or nationalist references in their names. The restaurant “Zum Elsässer” can be considered an example. The name can be understood as an allusion to Alsace, which was claimed by both Germany and France. The establishment “Zum alten Luftschiffer,” which boasted an iron cross in its facade design, seems to have also been frequented by soldiers, as visible on the postcard.

Some of these establishments were also meeting places for opponents of democracy and the Weimar Republic in the 1920s and were later used as so-called “storm pubs” by the Nazi Sturmabteilung (Storm Division, SA). From 1933, SA members arbitrarily detained people in such establishments, sometimes torturing and murdering them there. Some establishments, such as the restaurant “Zum Kaiserstein” on today’s Mehringdamm, were continuously sites of fascist practices: this early SA storm pub remained an important meeting place for right-wing extremists in Kreuzberg until the 1970s. Vigorous counter-protests by local initiatives eventually prevented the meetings in the establishment.

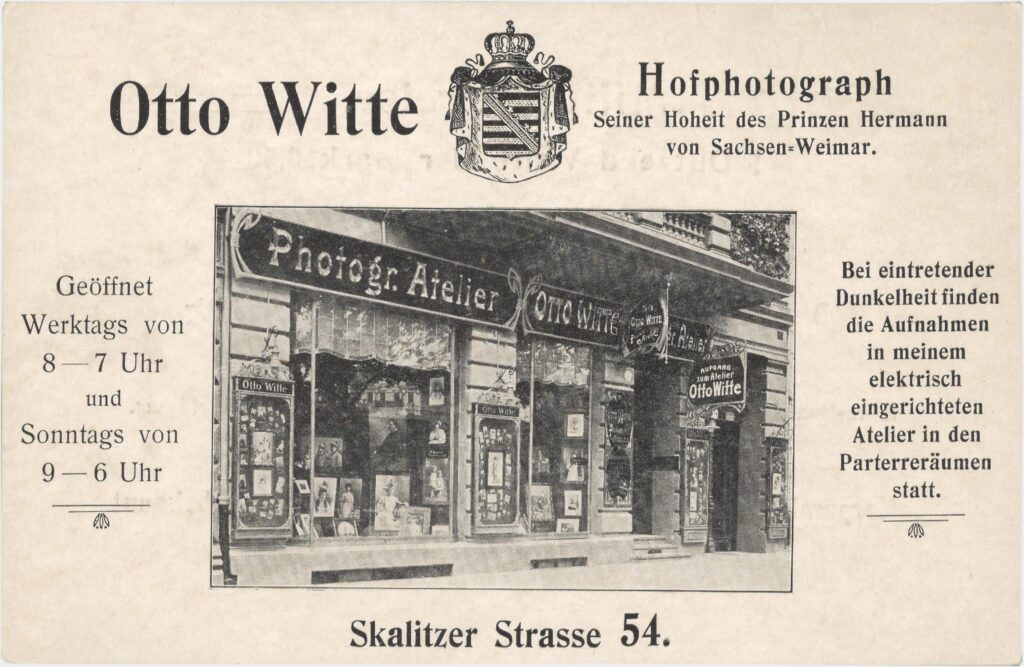

The Military as an Economic Factor

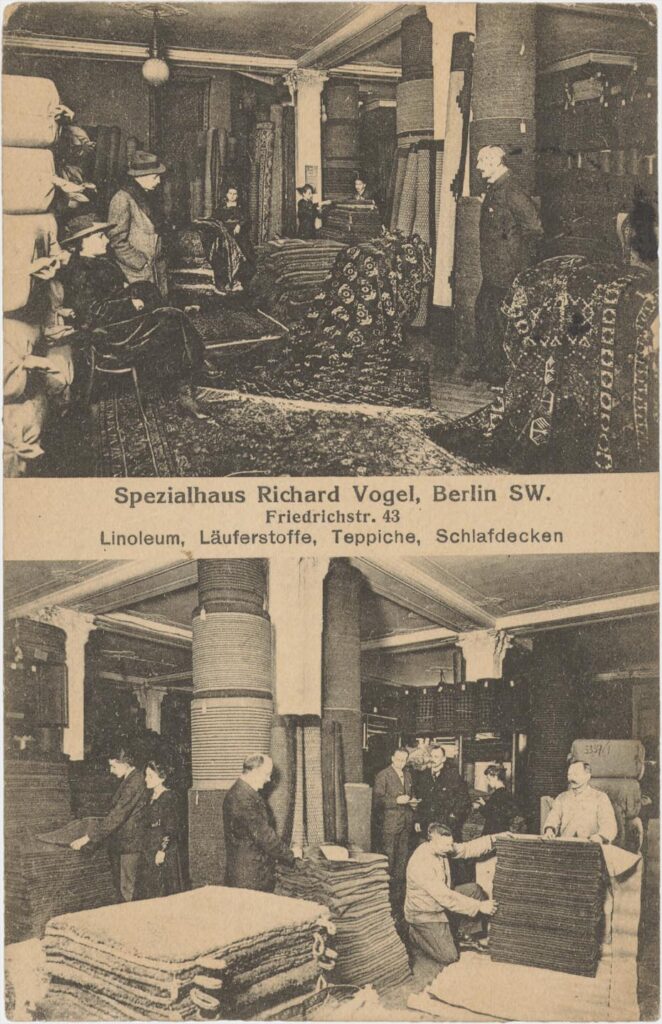

At the beginning of the 19th century, the military use of the Tempelhof suburb, now the western part of Kreuzberg, reached its peak. The soldiers stationed there not only needed weapons and ammunition but also had to be supplied with food, clothing, and other daily necessities. These were not centrally procured but were obtained extensively from the immediate surroundings. Therefore, many craft businesses settled around the military sites in the area, becoming dependent on their orders. Equipment, uniforms, and uniform parts were partly produced in industrial factories, partly in home-based manufacture, and then offered for sale in so-called military ornament shops. While facilities such as the garrison bakery provided soldiers with basic supplies, there were also shops that catered to more specific military needs. For example, the “Photogr. Atelier Otto Witte” offered special prices for photographs of military personnel. Thus, a distinct economic sector emerged in Kreuzberg, dedicated to fulfilling military needs. With demilitarization after World War I, many of these businesses lost their livelihood.

Kreuzberg in Rhythm

Soldiers marched through Kreuzberg every day on their way from their barracks to Tempelhofer Feld, accompanied by a military band. This showed again the constant presence of soldiers in the lives of Kreuzberg residents. For the regiments and their commanders, the marches were an opportunity for self-presentation, as they repeatedly attracted attention and were photographed for postcards, for example. On some postcards, individuals have marked themselves, presumably to send the card to relatives.

Larger military parades were a welcome spectacle in the everyday life of Berliners. For example, on the “Kaiser’s Birthday” on January 27 or “Sedan Day” on September 2, which celebrated the capitulation of French troops in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, countless spectators flocked to the route. They gathered along the way from the city palace to Tempelhofer Feld to witness the parades. Since the Prussian military cult was meant to demonstrate the unity of the army, the emperor, and the nation free from politics, political groups and associations were not allowed to participate in the parades.

Political protests were largely absent. However, jeering youths often imitated the marching soldiers, which was considered an insult to the military by the police and was punished. Suspecting these to be political demonstrations, the secret police tried to ban the march music in 1901 to prevent these so-called “troop escorts.” Although the ban could not be enforced, it is an illustrative example of how sensitive the state was to perceived criticism of the “military cult.”

Everyday Life of Soldiers in Kreuzberg

Peter Plewka’s postcard collection includes some motifs that depict the everyday life of soldiers in Kreuzberg, offering a somewhat ironic glimpse into everyday life in the barracks. However, it lacks references to the numerous downsides of service in the Prussian military. The lower officer ranks were off-limits to Social Democrats and Jews, for instance. Most officers in Berlin came from the nobility. At the 1st Guard Dragoon Regiment, for example, all 26 officers in 1913 were of noble birth. Various reforms between 1814 and 1918 allowed wealthier citizens — but not all — to enter the lower officer ranks. Since completing service as a noncommissioned officer was mandatory for a higher career in public service, certain groups were thus barred from careers as civil servants or teachers. The severe drills, numerous harassments, and even mistreatment that ordinary soldiers endured during their three to twelve years of service are not shown on the postcards.

Author

Maximilian Gärtner

MA Public History

LITERATURE

Teske, Hermann: Berlin und seine Soldaten. 200 Jahre Berliner Garnison. Berlin 1968. Haude & Spener Verlag.

Brücker, Eva: Kaserne des 1. Dragoner-Garde-Regiments. In: Engel, Helmut; Jersch-Wenzel; Stefi; Treue, Wilhelm (Hg.): Geschichtslandschaft Berlin (Bd. 5) Kreuzberg, Berlin 1994. Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung.

Vogel, Jakob: Nationen im Gleichschritt. Der Kult der „Nation in Waffen“ in Deutschland und Frankreich, 1871 – 1914. Göttingen 1997. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.