- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

COLONIAL KREUZBERG

The colonial ambitions of the German Empire at the end of the 19th century aimed to gain national prestige and demonstrate economic prominence compared to other imperial powers. Although imports from the German-occupied territories in Africa, China, and the Pacific were relatively insignificant economically, colonialism increasingly influenced the overall economy of the Empire from 1900 onward. Colonial goods also appeared in Kreuzberg, both as raw industrial materials in factories and as consumer goods in retail.

After the defeat in World War I, the German Empire lost its status as a colonial power and had to cede its colonies to the victorious powers in 1919. However, this did not end the colonial systems of rule and trade. An everyday example of this is the continued sale of goods of colonial origin, also in Kreuzberg.

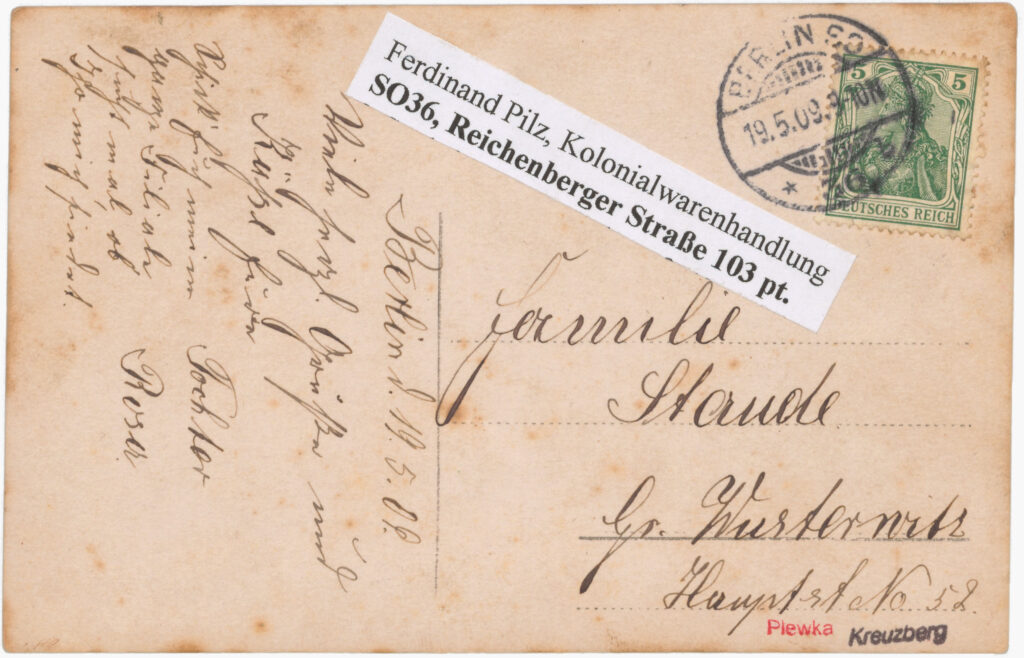

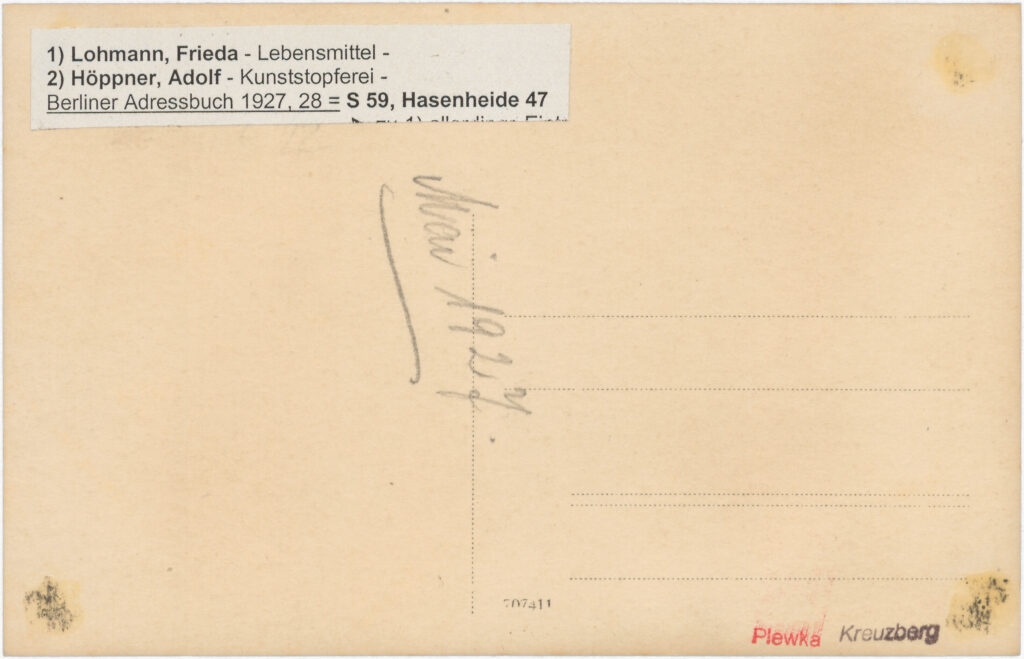

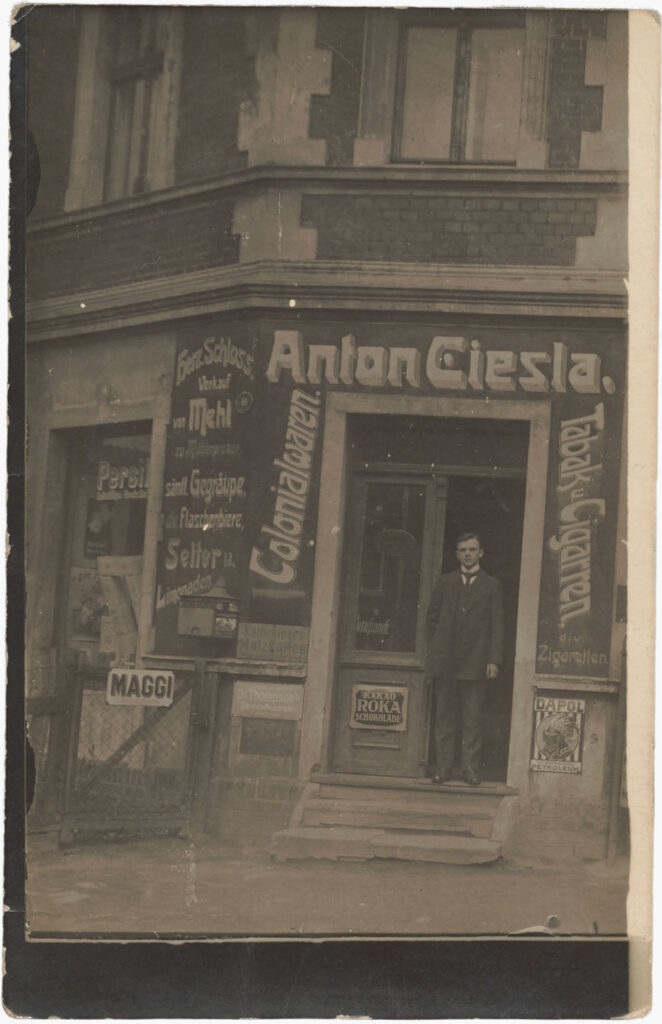

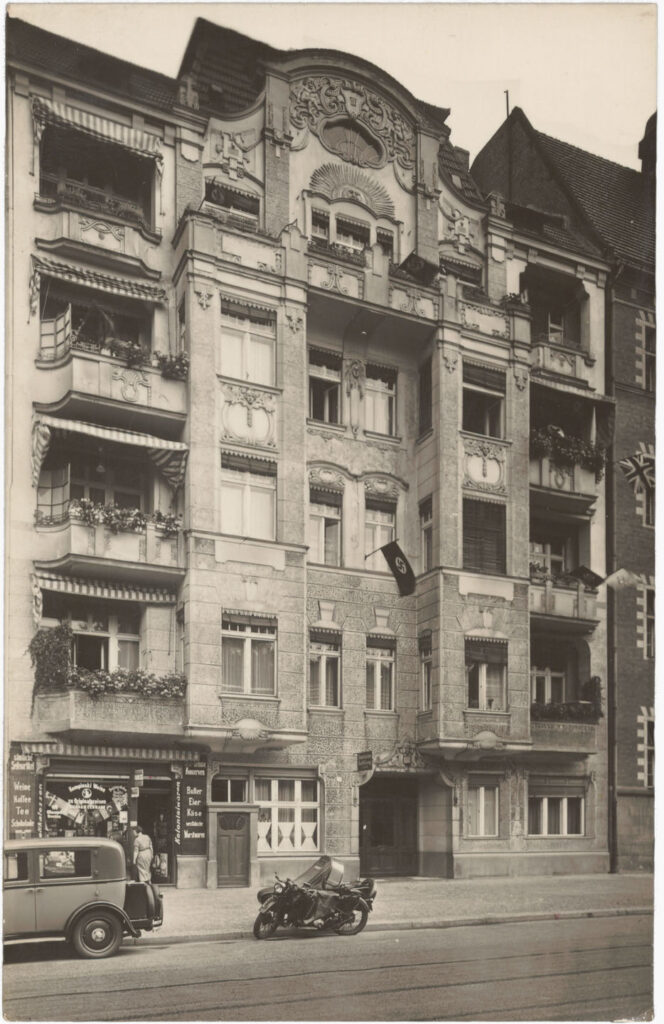

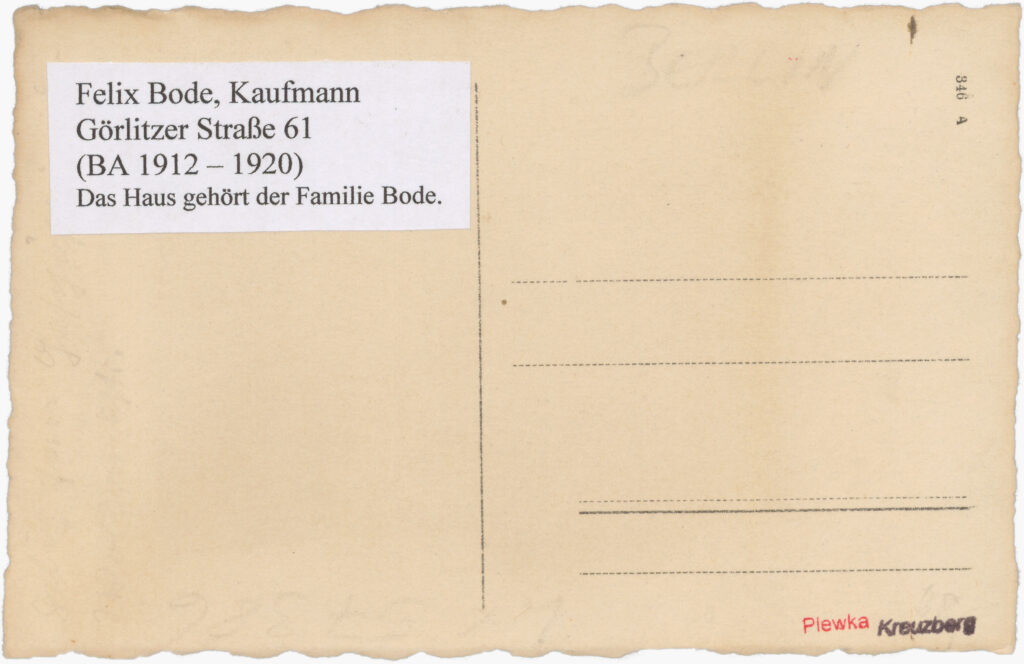

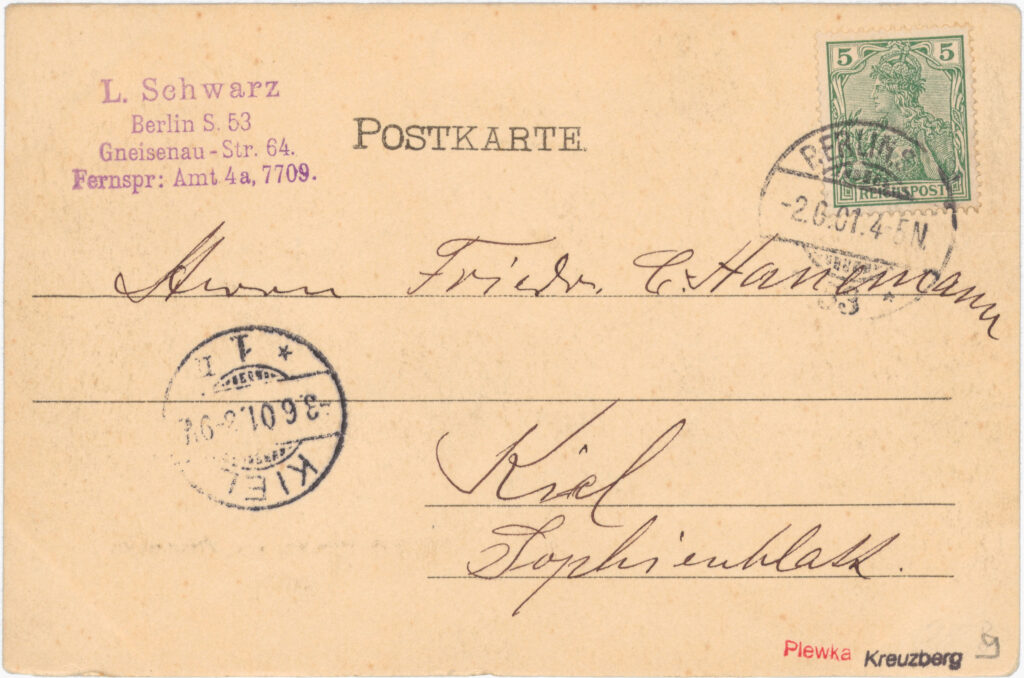

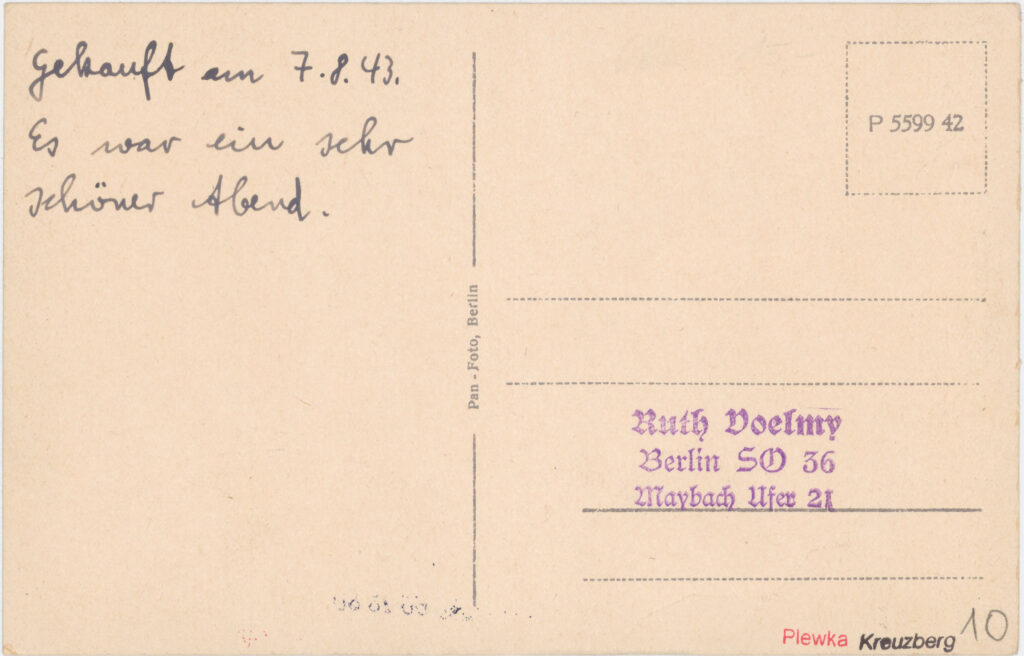

Peter Plewka’s collection of postcards begins around 1890. It depicts colonial rule more or less directly within the urban daily life of that time. On many postcards, shopfronts bear the inscription “Colonial Goods,” often with shopkeepers or salespeople posing beside them. Although there are postcards showing locations where the administration of imports of colonial goods was based, these are not directly identifiable in the motifs. On the other hand, colonial imaginations in the form of “exotic” images, racist representations, and racist language are very clearly visible in some motifs.

Colonial Goods Stores

In Kreuzberg, around 1900, products from colonial territories such as coffee, sugar, tea, rice, spices, tobacco, and chocolate were widely available in retail. Concurrently with the beginning import of colonial goods, retail in Kreuzberg expanded. This was also related to the changing social structure: with industrialization, people began migrating in large numbers from the countryside and from afar into the cities, including Kreuzberg. Instead of relying on their own production and barter for food as before, the incoming workers now depended on local retail for their purchases. In small shops, colonial goods were sold alongside everyday items, often on credit, making these products accessible even to working-class communities. The stores were frequently run by working-class women, who supplemented their low wages through sales.

Despite their everyday availability, colonial goods were considered luxury items, even though they were typically favored with customs and tax reductions. The widespread sale of these goods indicates that mass consumption had also reached the lower-income areas of Kreuzberg.

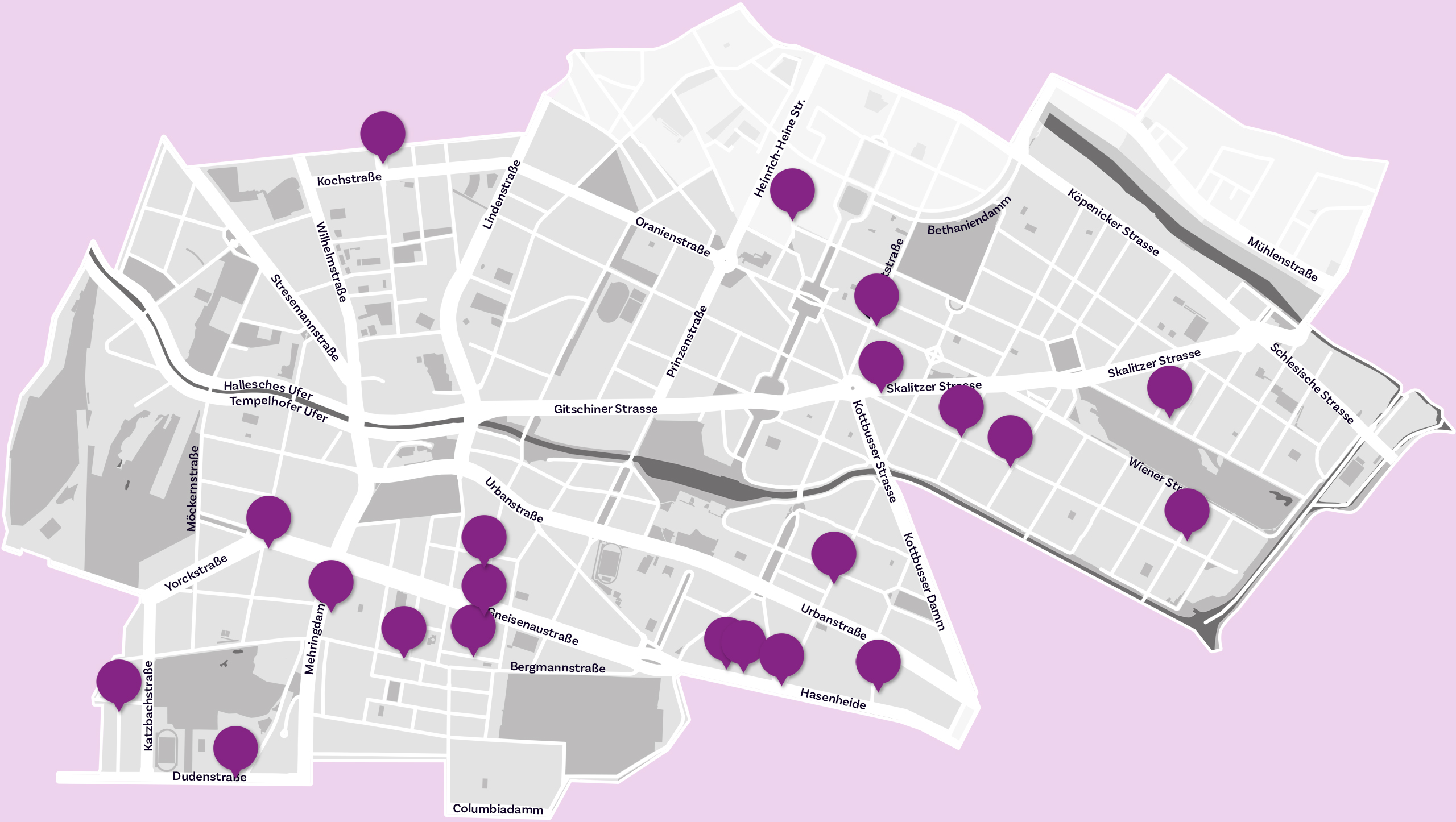

In Peter Plewka’s collection, there are postcards of colonial goods stores distributed throughout Kreuzberg. In front of some, employees or owners are posing, as is common with many other businesses regardless of their product offerings. The signs indicate that colonial goods were sold alongside everyday necessities such as flour, sausage, and potatoes.

Edeka

From the 1880s onward, products such as coffee, sugar, tea, rice, spices, tobacco, and chocolate were imported to Germany as part of German and global colonialism. In 1898, over 20 local colonial goods, delicatessen, and grocery merchants established a purchasing cooperative at Mittenwalder Str. 12 to collectively obtain better prices for colonial goods. They named themselves the “Einkaufsgenossenschaft der Colonialwarenhändler im Halleschen Thorbezirk.” The cooperative model was successful and led to the creation of similar initiatives in Berlin. In 1907, this developed into a nationwide business association known as Edeka – derived from the Kreuzberg founding on Mittenwalder Str. Today, Edeka remains a well-known supermarket chain.

In Peter Plewka’s collection, there are no postcards of the exact address of the purchasing cooperative. However, two cards depict the neighborhood at that time. The views of the street appear ordinary – reflecting the everyday reality of colonial rule and colonial trade.

Imported Raw Materials

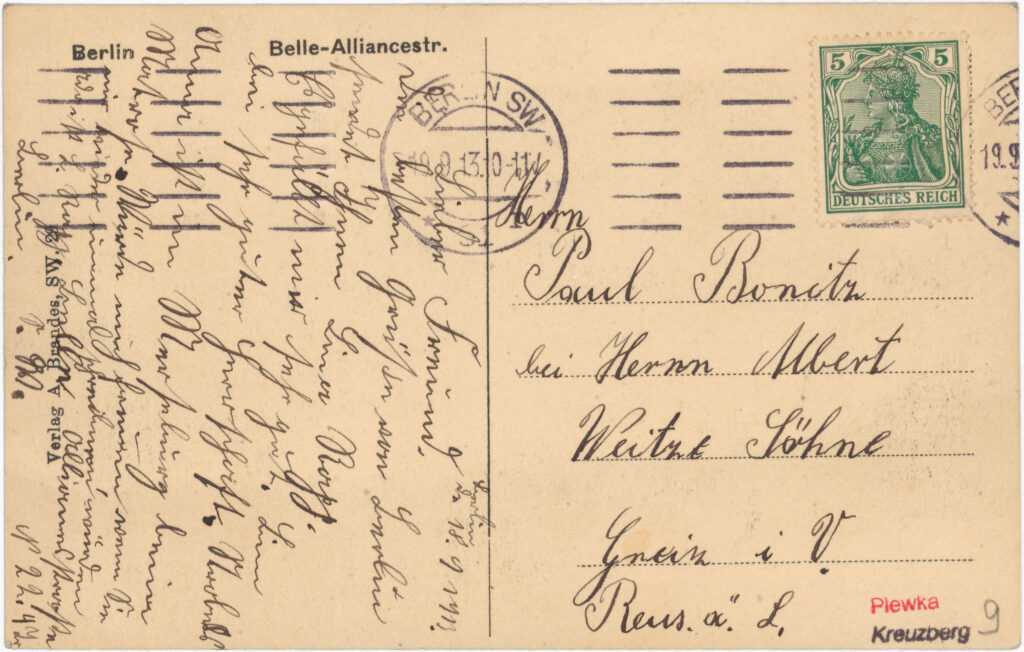

Around 1900, Kreuzberg was a major industrial site within Berlin, hosting many production facilities. Although the import of raw materials from German colonies was relatively modest, Kreuzberg’s factories processed colonial raw materials such as cocoa. The Berlin company Sarotti, one of the leading firms in the Reich’s chocolate industry, established its factory at Belle-Alliance-Str. 81 (now Mehringdamm 57) in the early 1880s. The site expanded, with neighboring properties at numbers 82 and 83 added in 1904 and 1906. By 1910, when the factory moved to Tempelhof due to space constraints, it employed 1,800 workers, most of whom were women.

Other factories also processed raw materials from colonized regions, such as ivory and silver, for fashionable household items, as well as in the jewelry and furniture industries.

In Peter Plewka’s collection, there are no postcards depicting the Sarotti factory, but there are images of Belle-Alliance-Str. (now Mehringdamm), where Sarotti produced its goods. These images highlight the urban daily life of Kreuzberg at that time.

Entertainment in “Exotic” Settings

Around 1900, cultural representations in the German Empire increased, aiming to visually depict the newly colonized territories in Africa, China, and the Pacific. These representations helped establish colonial possessions as “emerging homelands” and integrate them into the imperial-national fabric of the Empire as self-evident part of the everyday. Newspaper reports, feature articles, illustrations in magazines, postcards, advertisements, and the first so-called “ethnological exhibitions” shaped perceptions and discourses about colonial territories, their inhabitants, and their cultures. The resulting plethora of colonial racist imagery was continuously adopted, staged, popularized, varied, and legitimized in culture and entertainment.

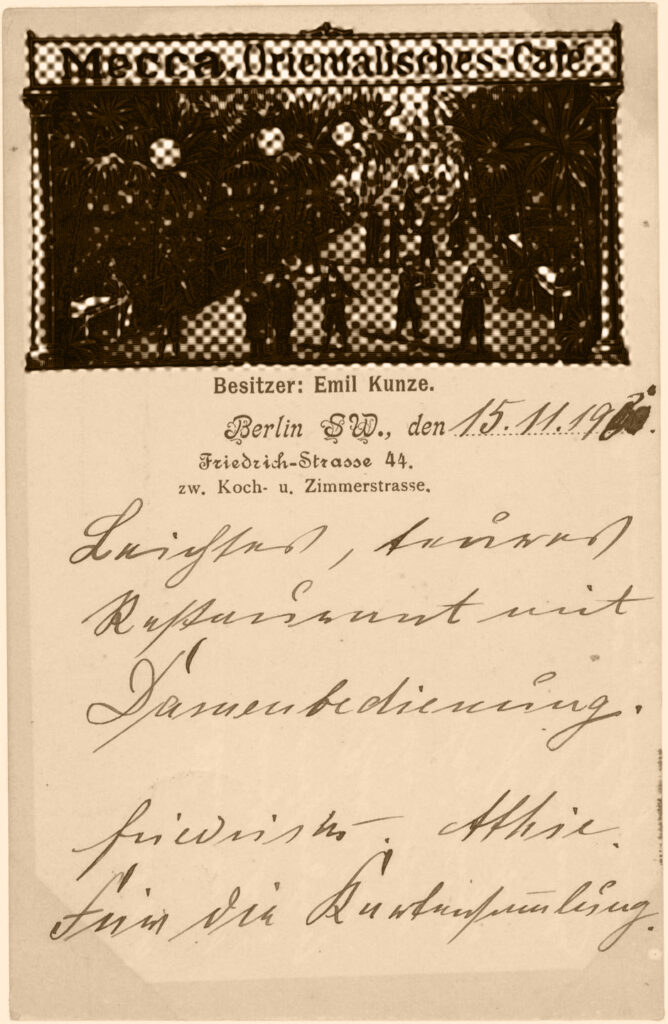

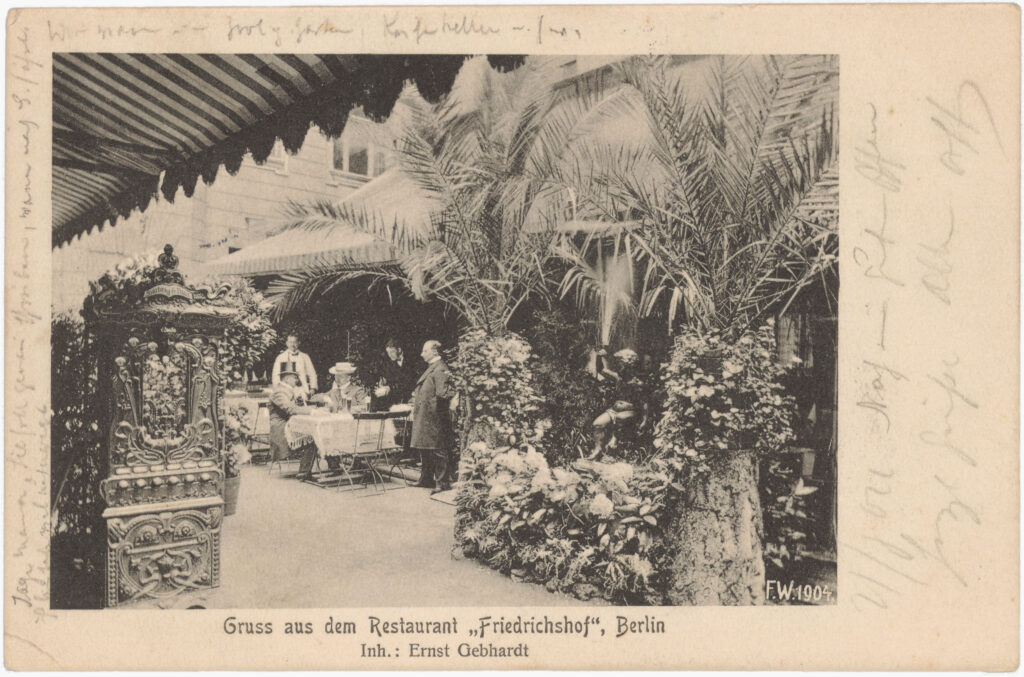

This constant repetition is particularly evident in Peter Plewka’s collection of Kreuzberg’s gastronomy postcards, whose “exotic” interior designs featuring plants, animal decorations, and weapons, as well as racist labelings contributed to normalizing and reproducing colonial power relations in daily life.

Between 1900 and 1920, this staged “exoticism” was not only popular in gastronomy but also permeated many areas, reaching broad segments of the population. “Exoticism” was associated with sensual intensity, primitiveness, “paganism,” and “savagery.” Both people and plants, customs, and food were staged as “exotic.”

Colonial Racist Advertising in the Chocolate Industry

Around 1900, the advertising industry used motifs of the “alien” and “exotic” as eye-catching elements in nearly all contexts. These representations drew on contemporary clichés and stereotypes of the “racially inferior” by exaggerating and racially embedding perceived ethnic traits. Such images often depicted colonized people at work or at festivals, usually portrayed as “primitive” and “uncivilized” through nudity. These depictions emphasized the “successful” subjugation of the colonized by the colonial rulers, portraying colonization as a supposed “blessing” for people in the colonies.

Colonial imagery was particularly prevalent in advertisements for products from the colonies, such as tobacco, soap, or chocolate. This advertising strategy also served to obscure or overshadow the exploitative production conditions of these products.

Collectible Cards from “Hartwig & Vogel”

The Dresden company “Hartwig & Vogel” produced chocolates from imported colonial cocoa and was, alongside Sarotti and Stollwerk, one of the leading companies in the chocolate industry. As part of their advertising strategy, they distributed collectible cards featuring colonial imagery, such as “cheerful” and working colonized people contrasted with German colonial rulers depicted as superior.

Sarotti

The Berlin chocolate company Sarotti also used racist clichés in their advertising, for example on a poster for cocoa featuring two Black men, clad only in loincloths, carrying a massive banana plant on their shoulders with the aid of a pole. In 1918, Sarotti created one of the most popular figures in the history of German advertising, the Sarotti-M***, depicting a childlike, fairy-tale-like Black figure in the role of a servant.

Although Peter Plewka’s collection does not contain direct evidence of Sarotti advertising, several building signs suggest stores that sold Sarotti chocolate. It is likely that racist advertising images from the company were displayed at these locations.

Boers in Kreuzberg

A postcard from Peter Plewka’s collection shows a group of people in front of the restaurant Carl Saalmann, labeled “Gruss vom Buren-Lokal” (Greetings from the Boer Pub). The exact connection between the restaurant and the Boers is unknown. However, the label and designation as a “Buren-Lokal” indicate that Kreuzberg residents engaged positively with them.

The term “Boers” referred to the descendants of Dutch, German, and French settlers who had arrived in South Africa since 1652. They violently conquered territories and established so-called “Boer Republics,” where they exploited the indigenous population similarly to the colonial rulers. Between 1898 and 1902, the Boers fought a war against the British colonial power, which was interested in the mineral resources of their regions. Some German press in the Empire and in South Africa, as well as proponents of an “all-German” ideology promoting ethnic thinking and imperialist colonial politics, supported the Boers. Their struggle was seen as a useful means against the expansion of British influence in South Africa. Additionally, the Boers were considered “racially related” to the Germans, leading to “ethnic solidarities.” Supporters of these views likely gathered at the “Buren-Lokal” in Graefestr.