- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

KREUZBERG, THE NEWSPAPER DISTRICT AND ITS TRADE UNIONS:

Paula Thiede and colleagues

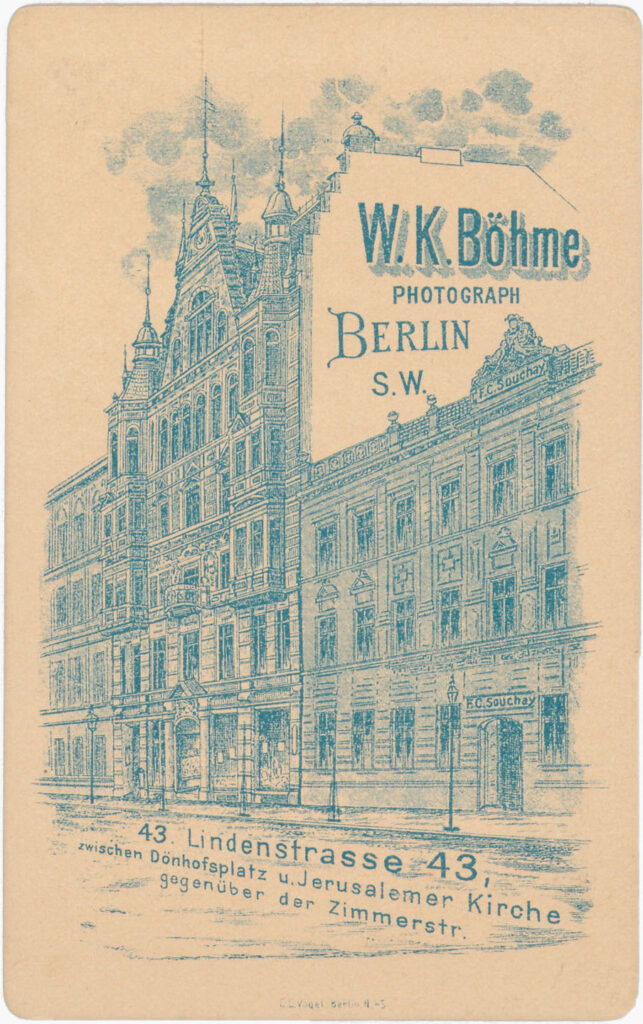

At the end of the 19th century, the world-famous Kreuzberg newspaper district was created on an area of around one square kilometer, bordered by Leipziger Str., the Landwehr Canal, Wilhelmstr., and Lindenstr. This happened as part of the industrial- ization of the printing industry. Important institutions of the workers’ movement were located in the immediate vicinity, including the party headquarters of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1902.

The newspaper district influenced the life of Paula Thiede, who initially worked as an unskilled worker in the printing industry and later became the first woman in the world to head a trade union. The life of the printer and writer Ernst Preczang was also closely linked to this quarter. He occasionally worked as an editor for “Solidarität”, the newspaper of Paula Thiede’s trade union.

Paula Thiede’s life story is not only closely linked to the newspaper district, but also to the rise of the labor movement, the beginning of women’s emancipation and the history of Berlin in the German Empire and the early Weimar Republic.

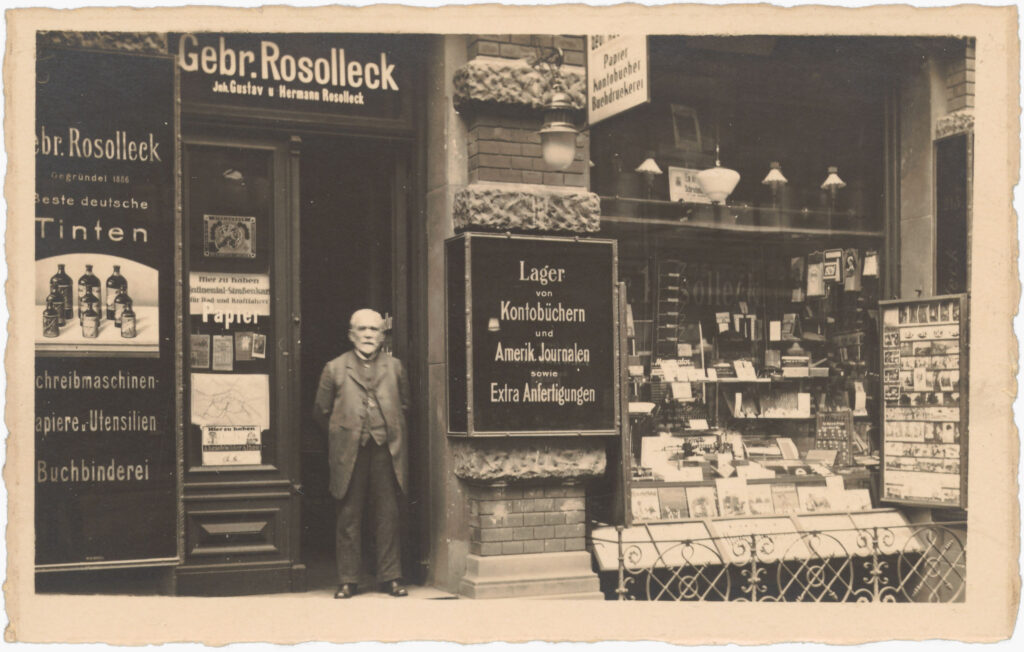

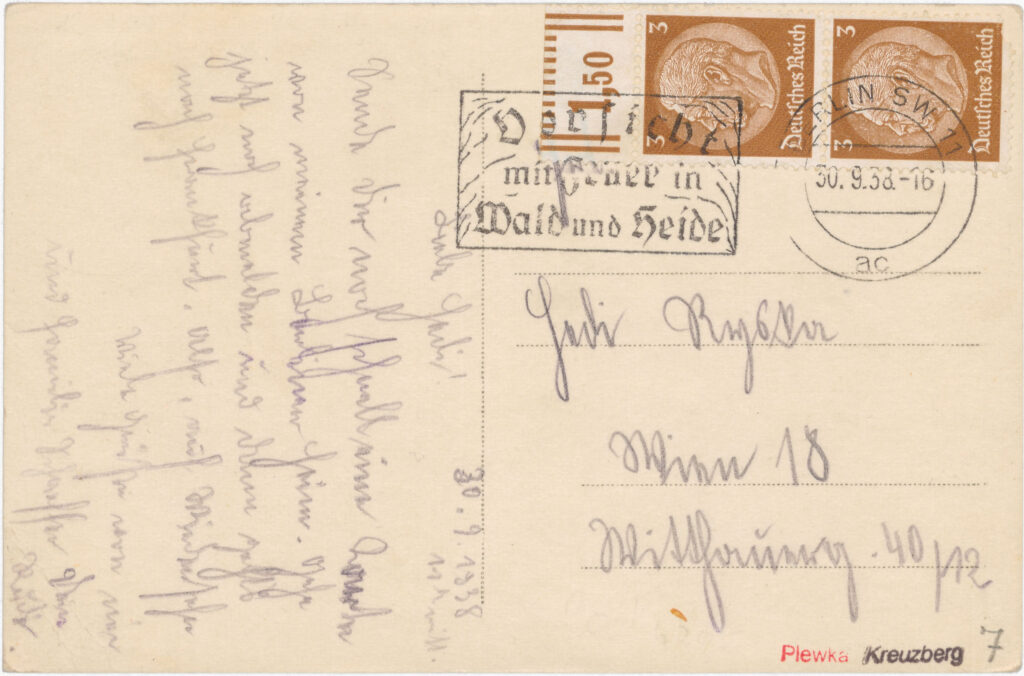

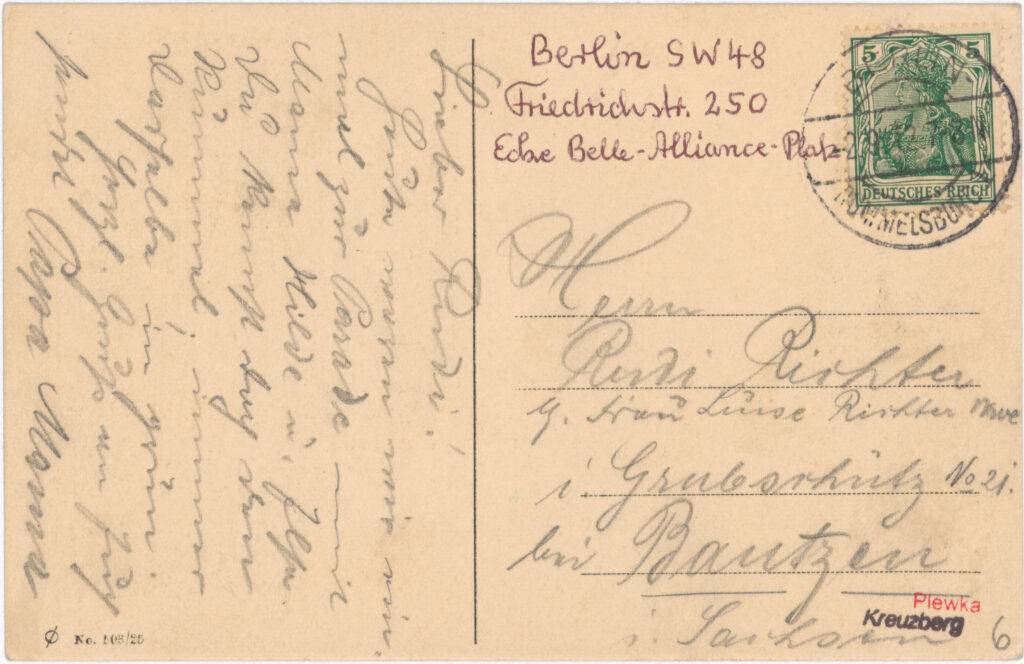

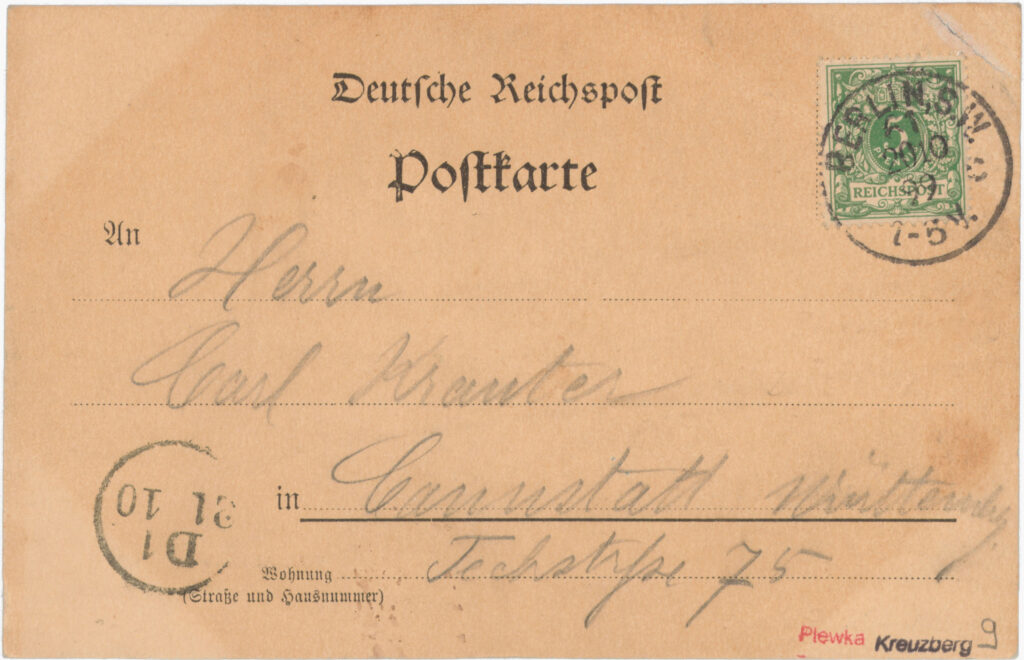

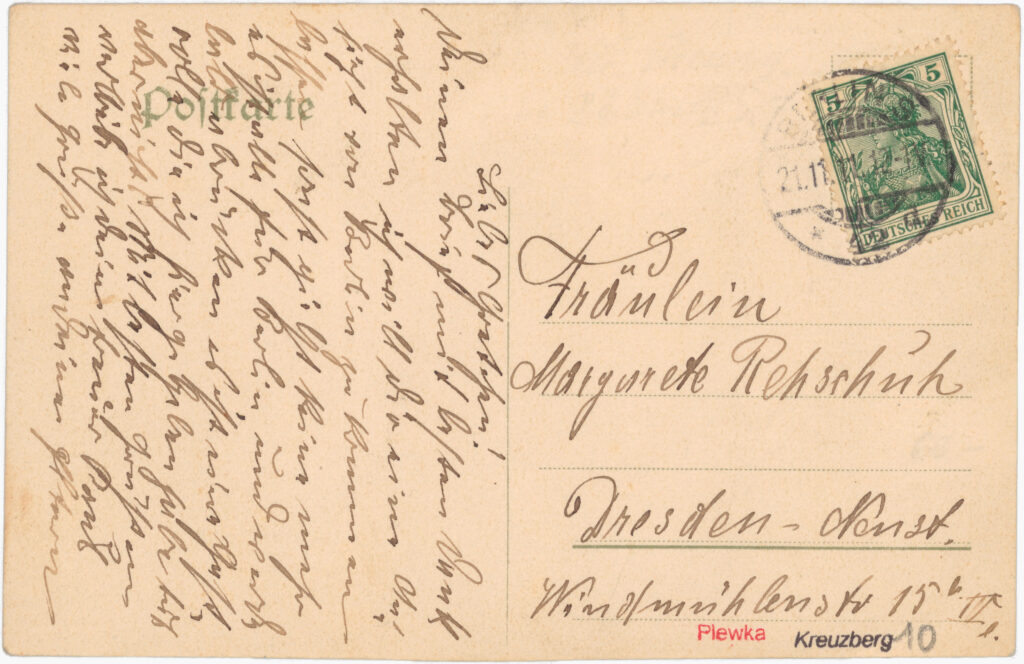

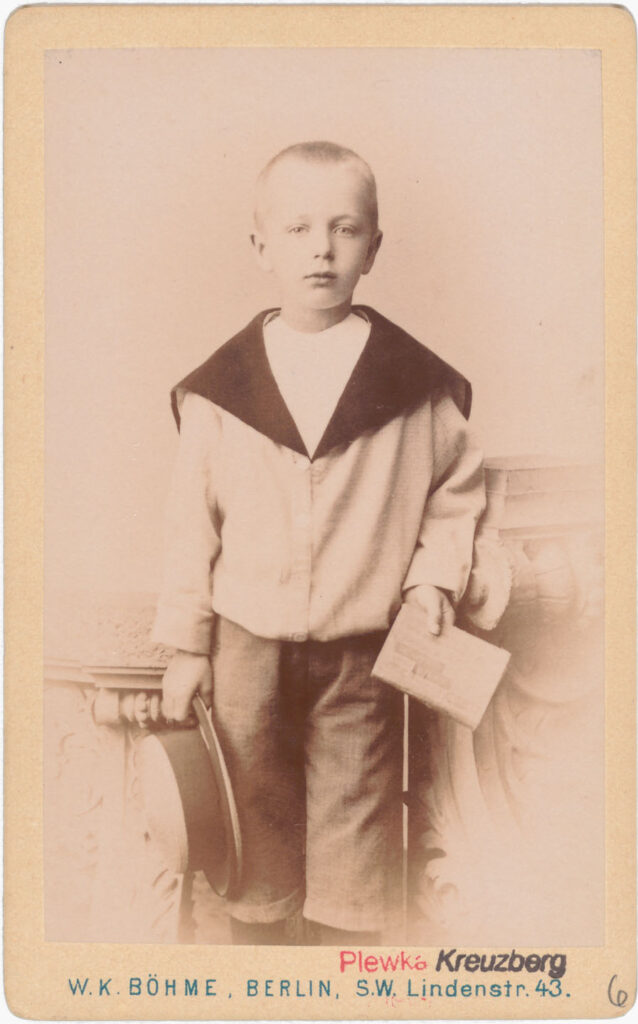

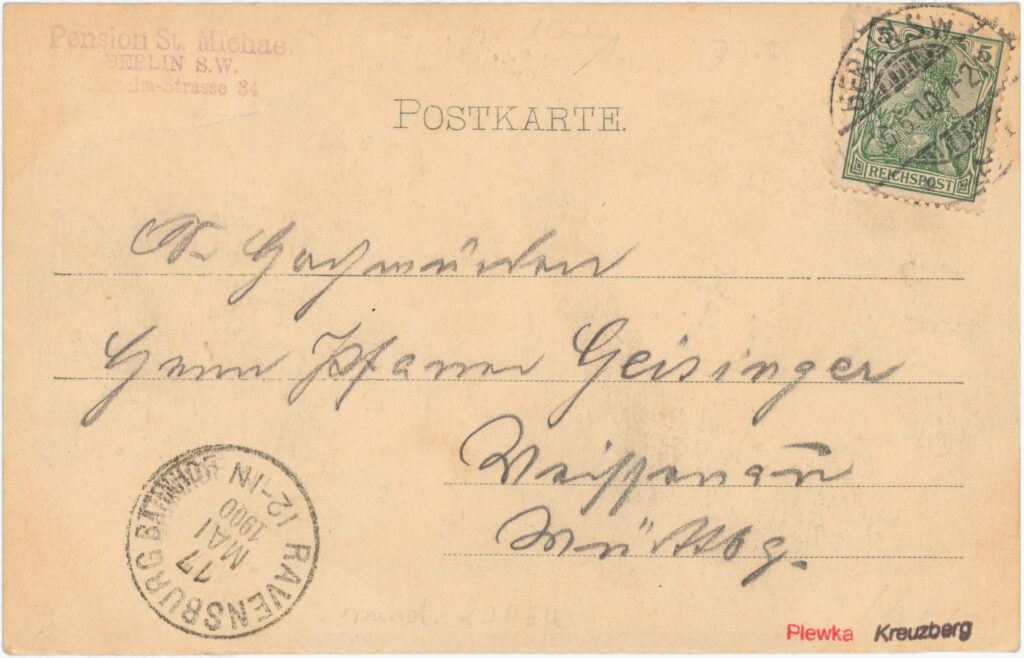

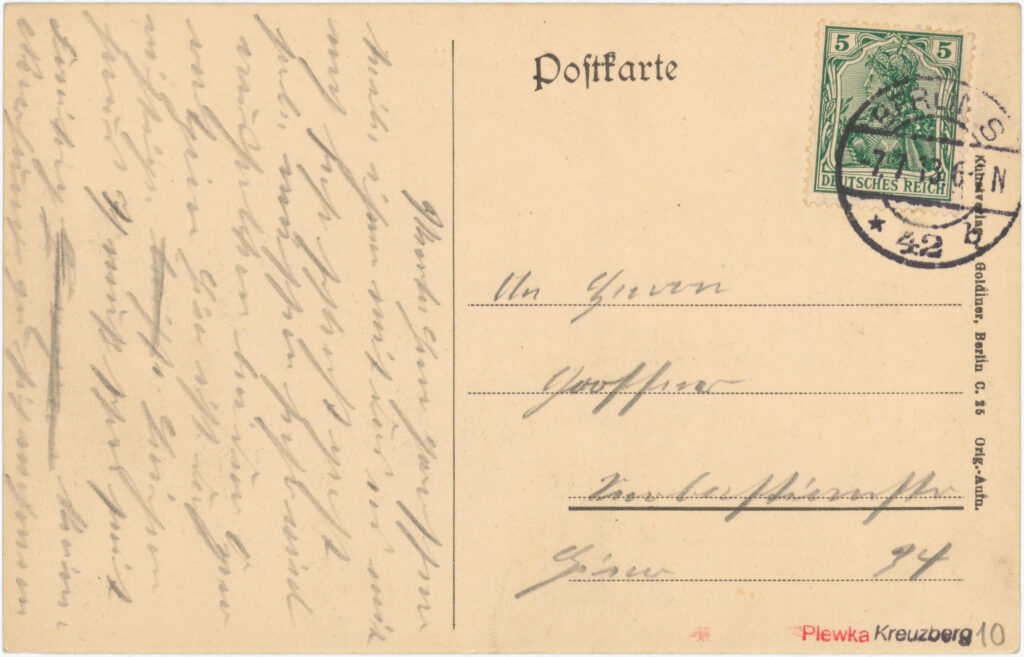

The Peter Plewka collection makes it possible to trace the places and lives of people such as Paula Thiede or Ernst Preczang, whose everyday lives are often barely documented in historical sources.

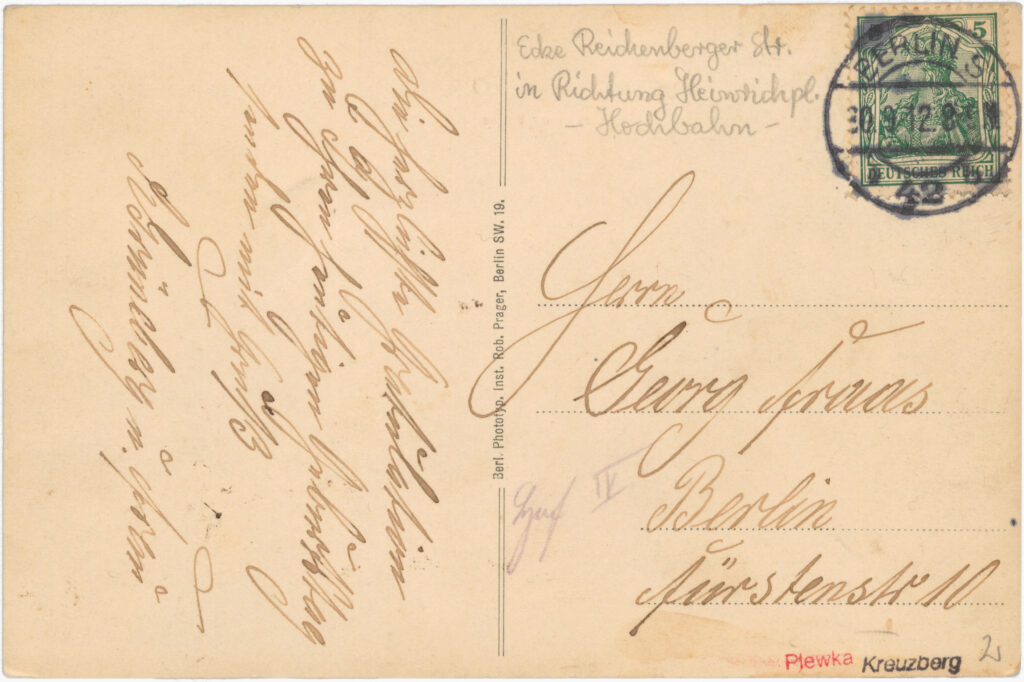

More than just newspapers: Politics, business and life in the newspaper district

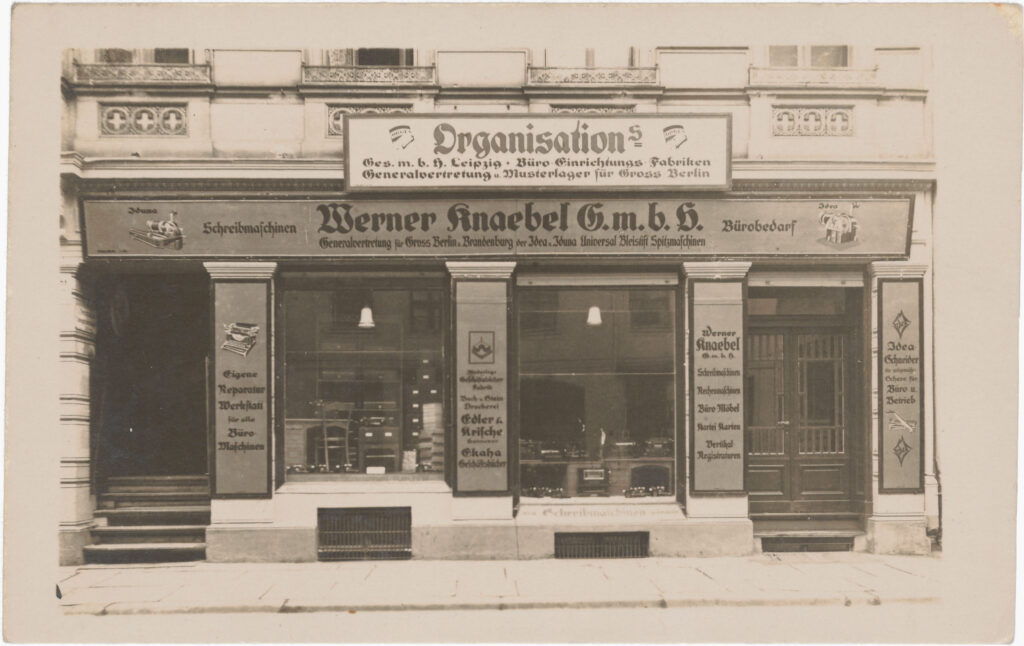

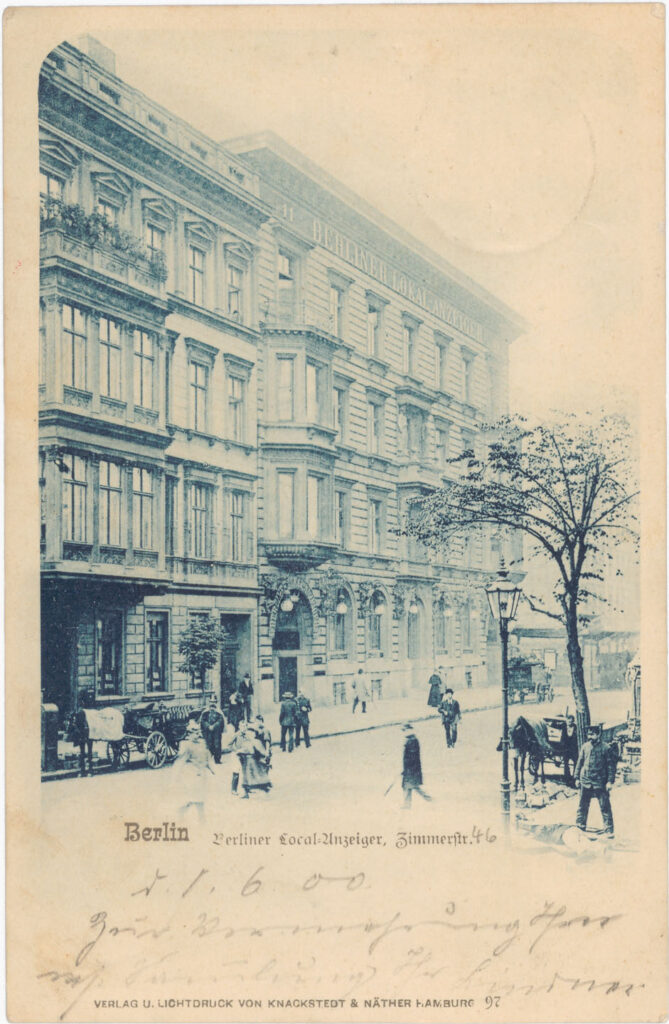

Numerous publishing houses of all sizes settled in the newspaper district in the 19th century. The best known were Scherl, Ullstein and Mosse. The social democratic Vorwärts-Verlag also had its headquarters, editorial office and printing works in Lindenstr. From the 1920s, Willi Münzenberg’s communist “Neuer Deutscher Verlag” was located on Friedrichstr.

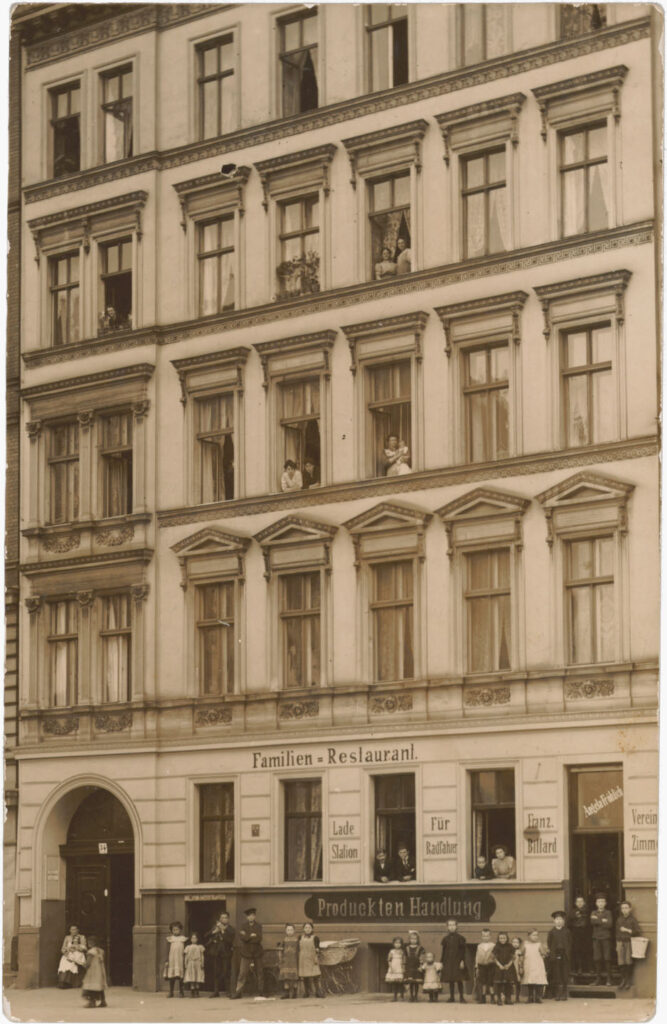

Around 500 businesses in the printing industry existed on the small site – from print shops, typesetters, and bookbinderies to countless editorial, advertising, and sales offices. Newspapers were sold hot off the press at kiosks and by street vendors and were literally snatched from their hands when there was a sensation.

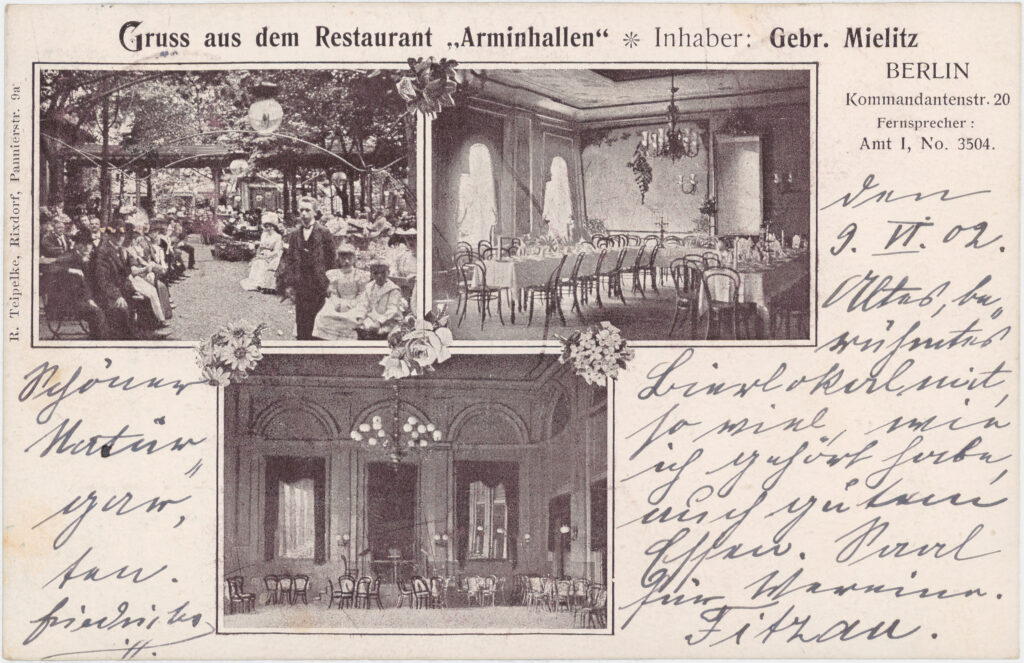

The neighborhood was buzzing. In addition to the publishing houses, there were also numerous stores in other sectors as well as entertainment venues such as theaters, famous cafés, hotels and, later, cinemas. Mostly invisible on the postcards, but always there: workers and trade unionists like Paula Thiede.

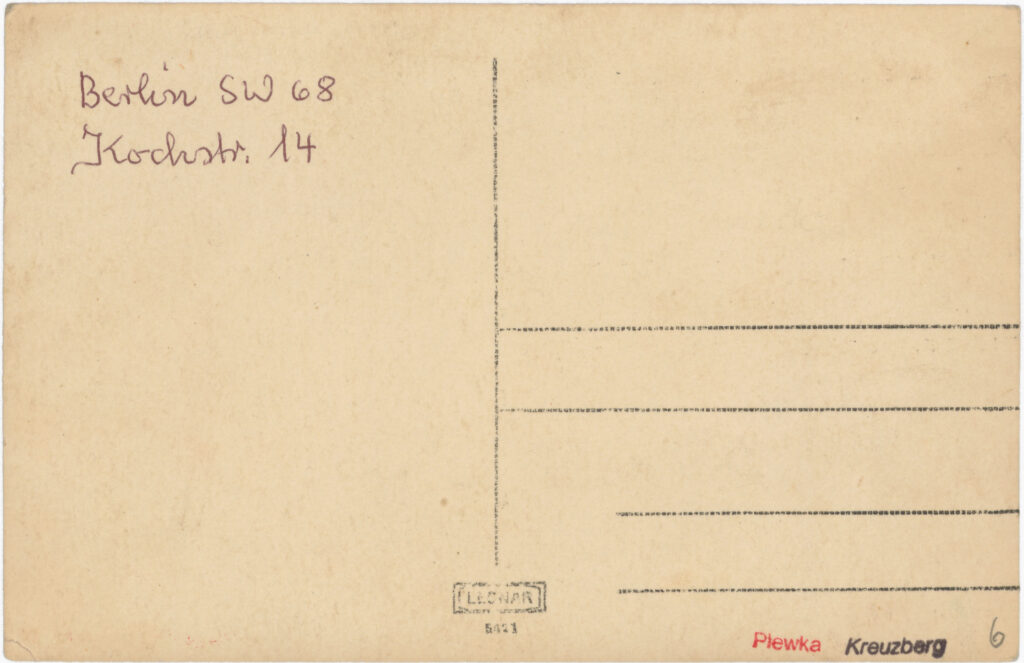

Zimmerstr. 36–41 was home to the Scherl publishing house, which published the high-circulation “Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger”, among other things. Right next door, the “Berliner Morgenpost”, the rival paper from the Ullstein publishing house, was sold. While the Scherl publishing house pursued a German nationalist line, the Ullstein publishing house initially had a more liberal agenda. Due to its personnel policy, the publishing house employed almost exclusively Jewish university graduates. From 1934, the Ullstein publishing house was “Aryanized” and adapted to the National Socialist ideology.

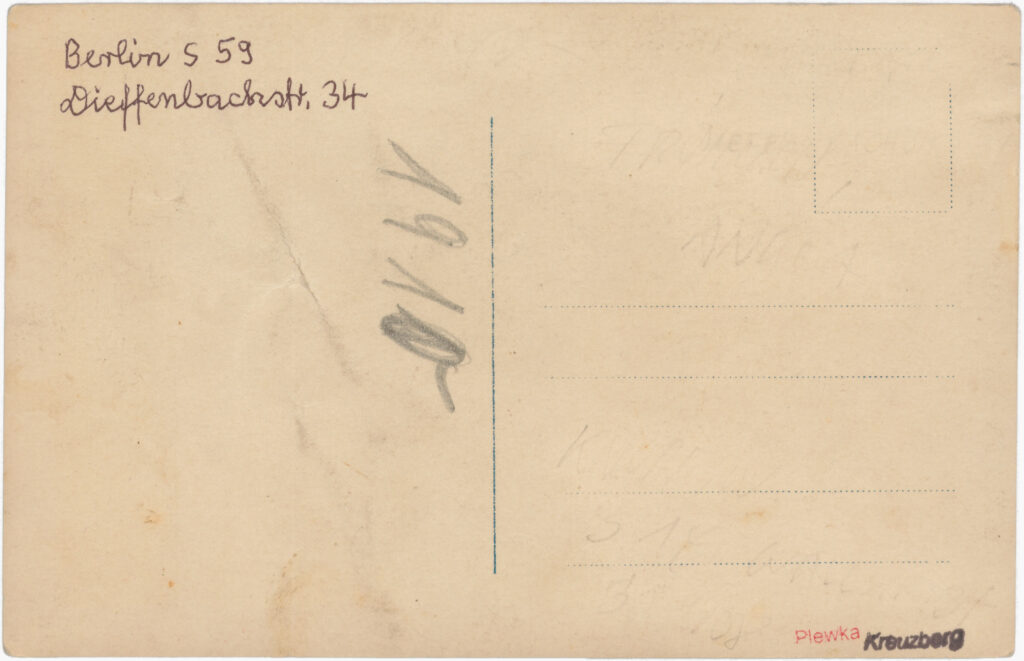

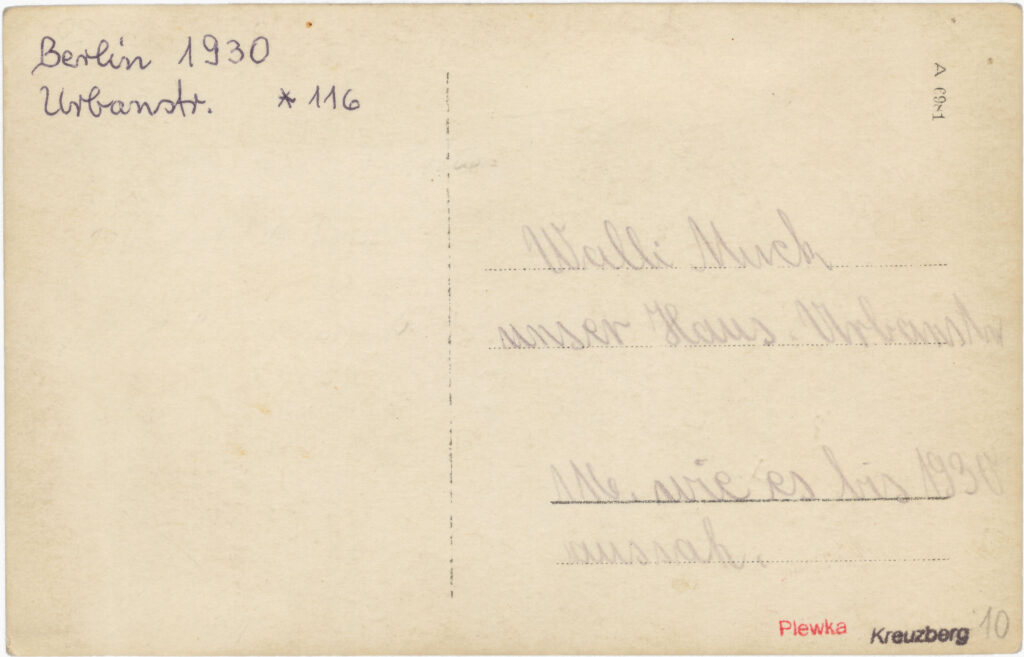

Many of the employees in the printing industry lived in the immediate vicinity of the newspaper district. Paula Thiede, born at Wilhelmstr. 20, moved to Friedrichstr. 250 in her youth, later to Waterloo-Ufer 4, then to Urbanstr. 36 and Dieffenbachstr. 31 in Kreuzberg’s Graefekiez. There were close-knit political networks of printing union activists in Graefekiez. Living and working were close to each other, even if the workplaces could change quickly, especially for colleagues who were willing to engage in conflict.

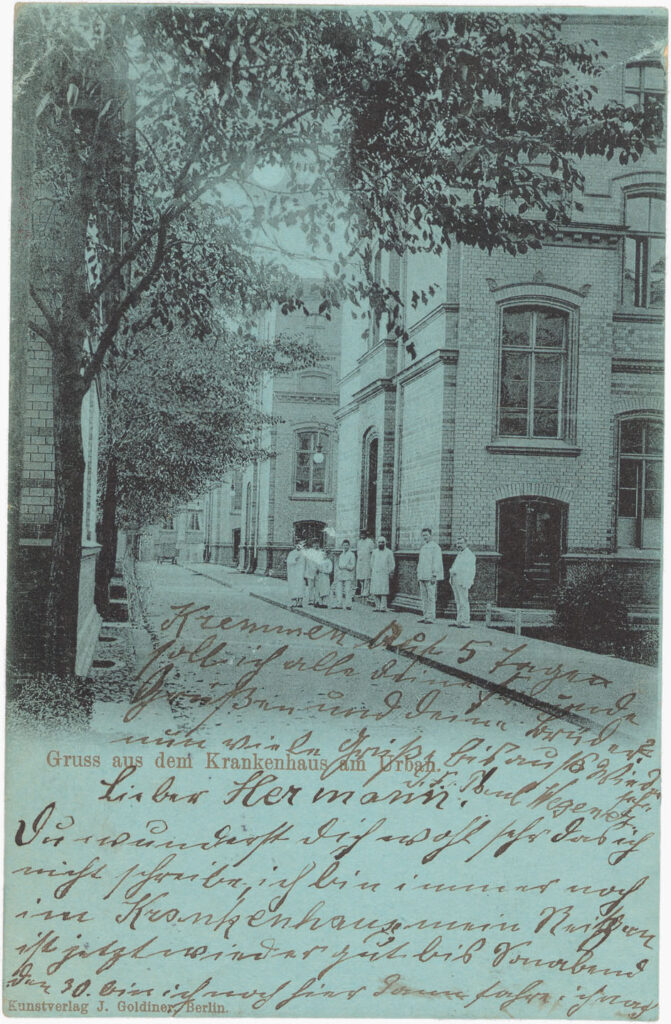

Earnings in the printing industry were higher than in many other professions. But employers ignored the health risks to workers. Chemicals, toxins and a lack of safety precautions often led to accidents, illness and early deaths – more than half of all printers did not reach the age of 40. These conditions are not directly reflected on the postcards, but they are reflected in Peter Plewka’s collection: the Urban Hospital, where Paula Thiede’s first husband, the letterpress printer Rudolf Fehlberg, was one of many to die at the age of 30 in 1891, was close to the newspaper district and the homes of many employees.

Pressure from below:

Trade unions in the newspaper district

Paula Thiede and many working women were incited by their despair over the injustices and misery of the workers to improve their own living conditions. After the abolition of the Socialist Law in 1890, they founded new associations.

One of these unions was the “Verein der Arbeiterinnen an Buch- und Steindruck-Schnellpressen” (Association of Female Letterpress and Lithographic Printing Press Workers). Paula Thiede joined at the end of 1891 – in the middle of an ongoing labor dispute among book printers for the 9-hour day. It was the biggest strike the empire had ever seen: In November 1891, 12,000 book printers went on strike – and with them thousands of book printing assistants.

In 1898, the associations of unskilled workers in the printing industry united to form a nationwide trade union, which was initially called the “Association of unskilled workers employed in book printing and related trades”; Paula Thiede became its chairwoman.

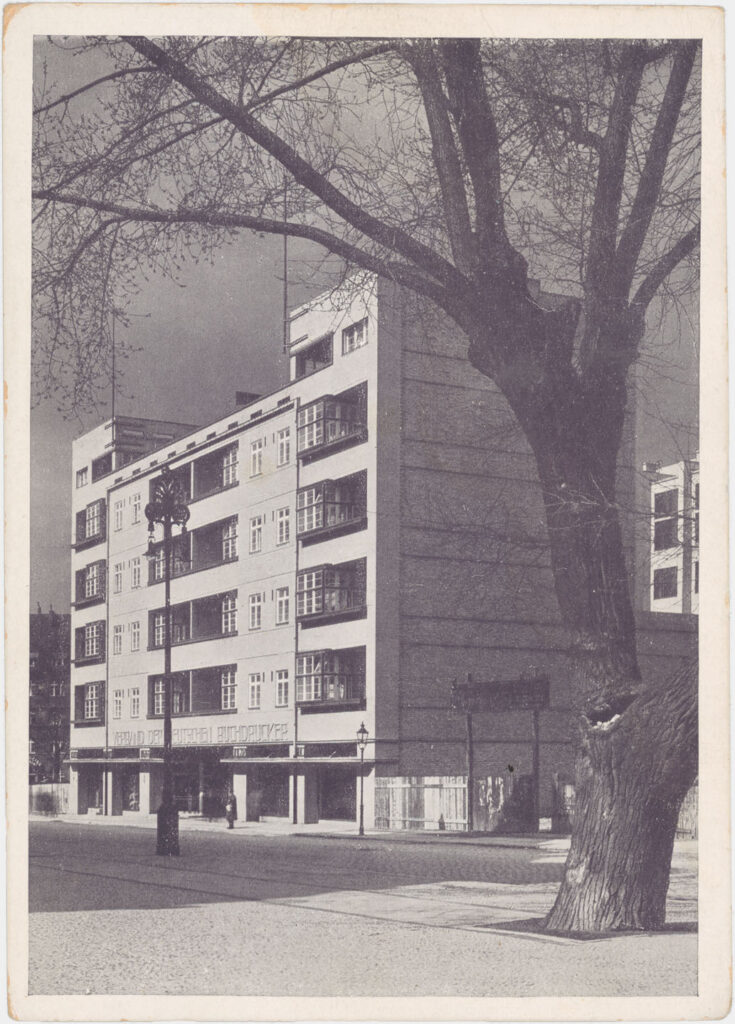

In 1926, the older and larger organization of exclusively male book printers set up a new headquarters at Dudenstr. 10, where the headquarters and printing works of the Gutenberg Book Guild were also located under the management of Ernst Preczang, who had previously worked at the Reichsdruckerei and was known as the “association poet” for Paula Thiede’s union.

Built in 1924 and completed in 1926, the “Buchdrucker-Verbandshaus in Berlin” at Dreibundstr. 5, now Dudenstr. 10, housed numerous offices, apartments, event, and exhibition rooms as well as a complete print shop in the rear building. As its “literary director”, Ernst Preczang was responsible for printing the volumes of the Büchergilde Gutenberg from 1926 – including the first edition of “Das Totenschiff”, which brought B. Traven worldwide fame in 1926. Like many trade union buildings, the “Haus der Buchdrucker” was occupied by the SA on May 2, 1933.

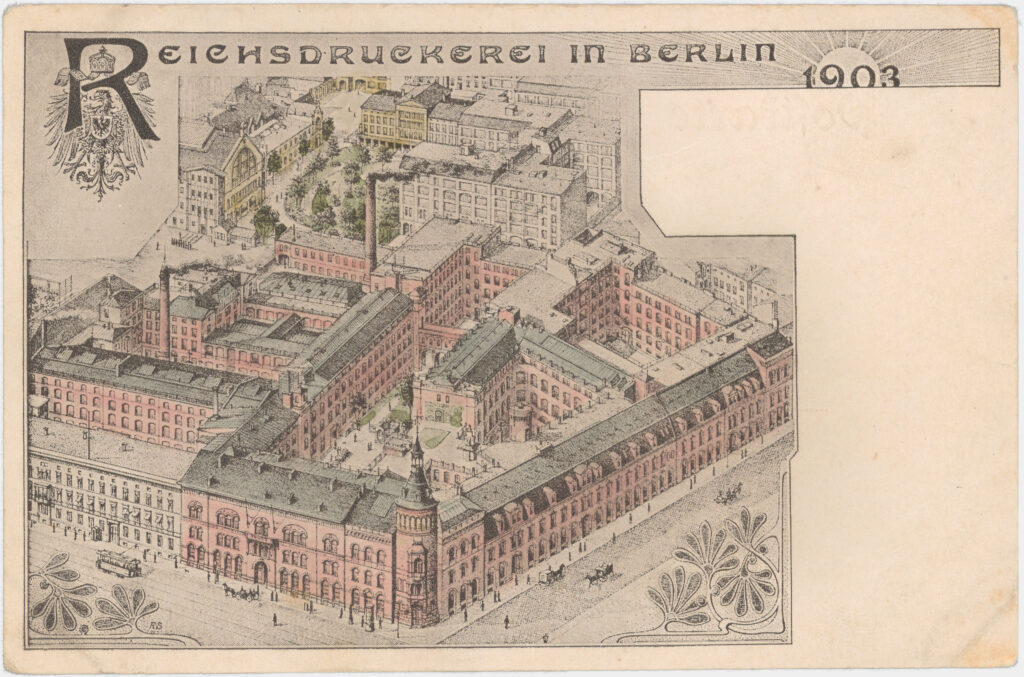

The Reichsdruckerei at the western end of Oranienstr. was the largest of all Berlin printing works. In 1886, 40 unskilled workers were dismissed after a wildcat strike––an event that is regarded as the initial spark for their unionization, which led to the founding of Paula Thiede’s trade union in 1898. In the years 1890–1895, Ernst Preczang also earned his living at the Reichsdruckerei.