- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

TRADE, CRAFT AND INDUSTRIES

Kreuzberg’s Work and Everyday Life

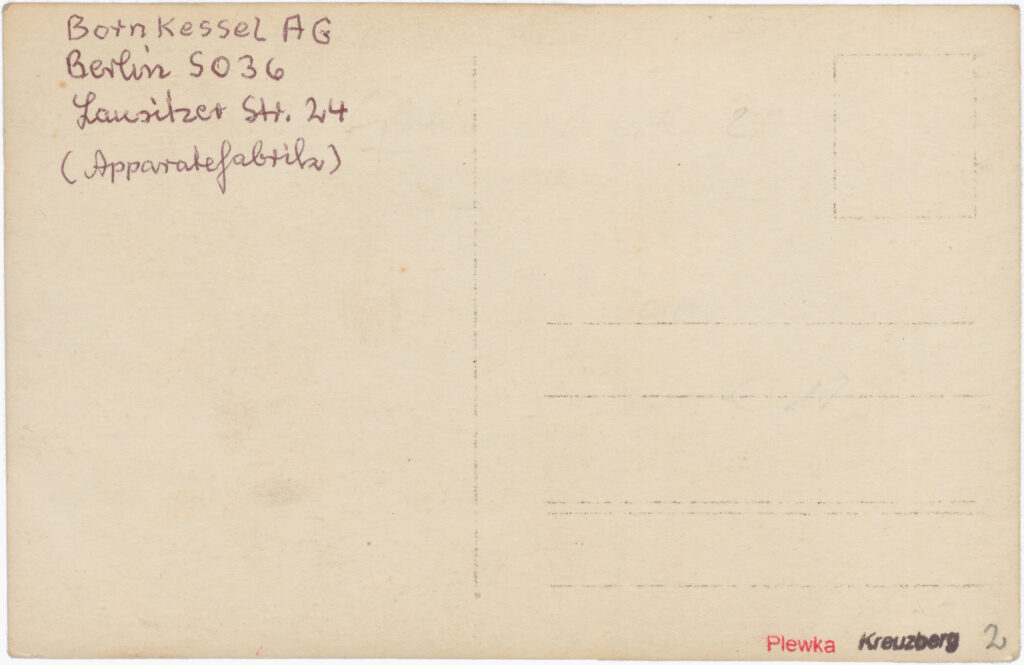

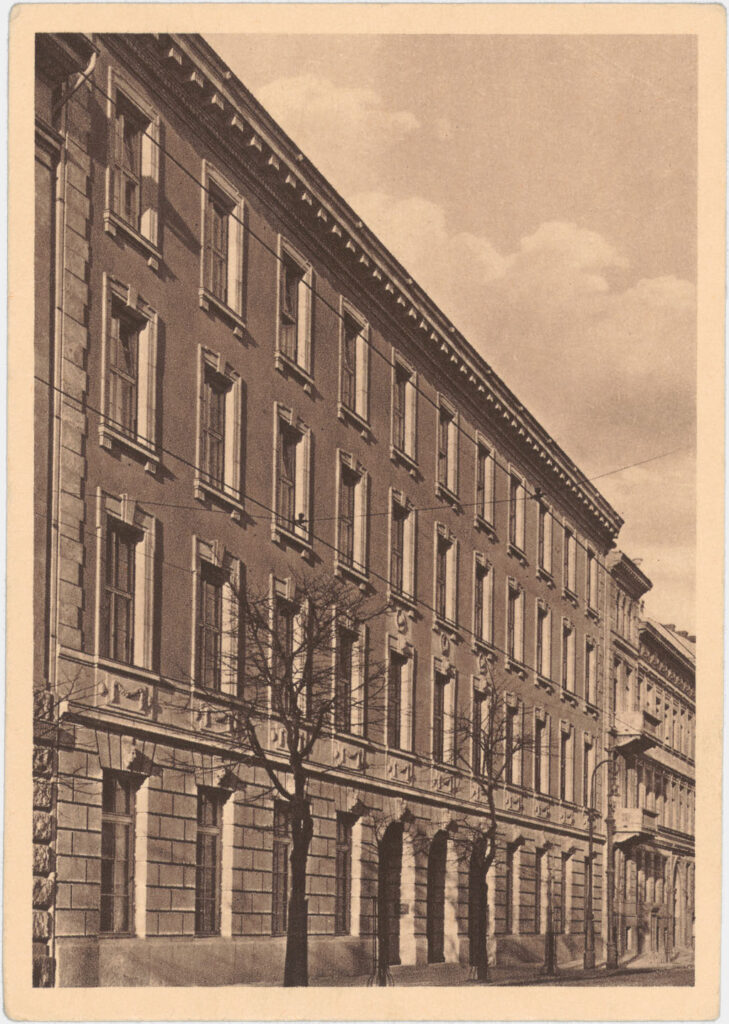

Since the beginning of the 19th century, more and more craft, service, and industrial businesses settled in the area that is now the Kreuzberg district. Until the end of World War II, Kreuzberg, due to the large number of businesses, was one of Berlin’s most important industrial locations.

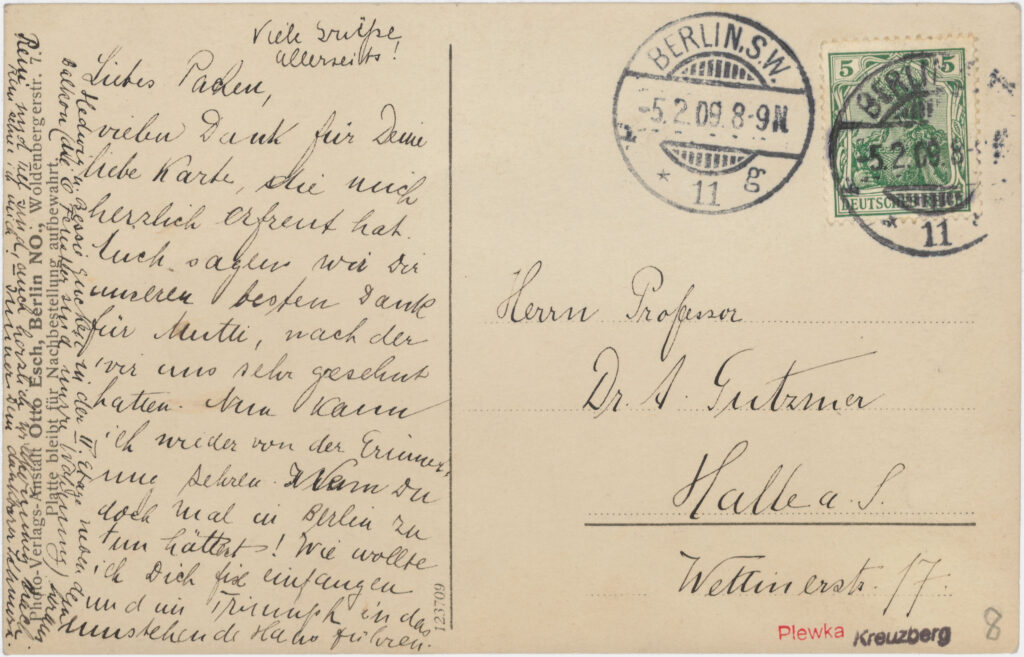

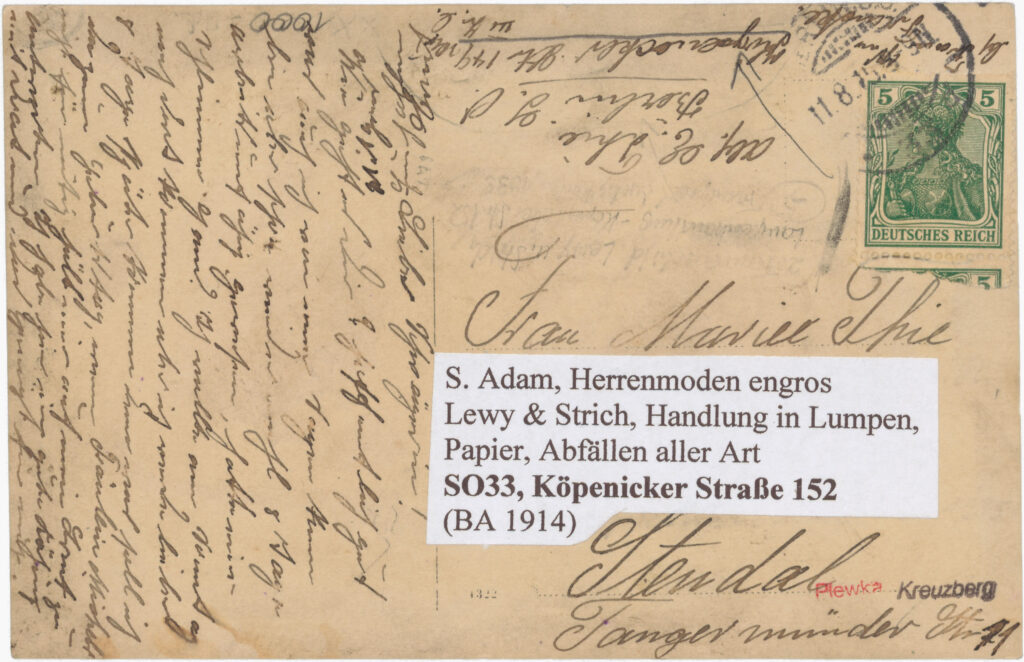

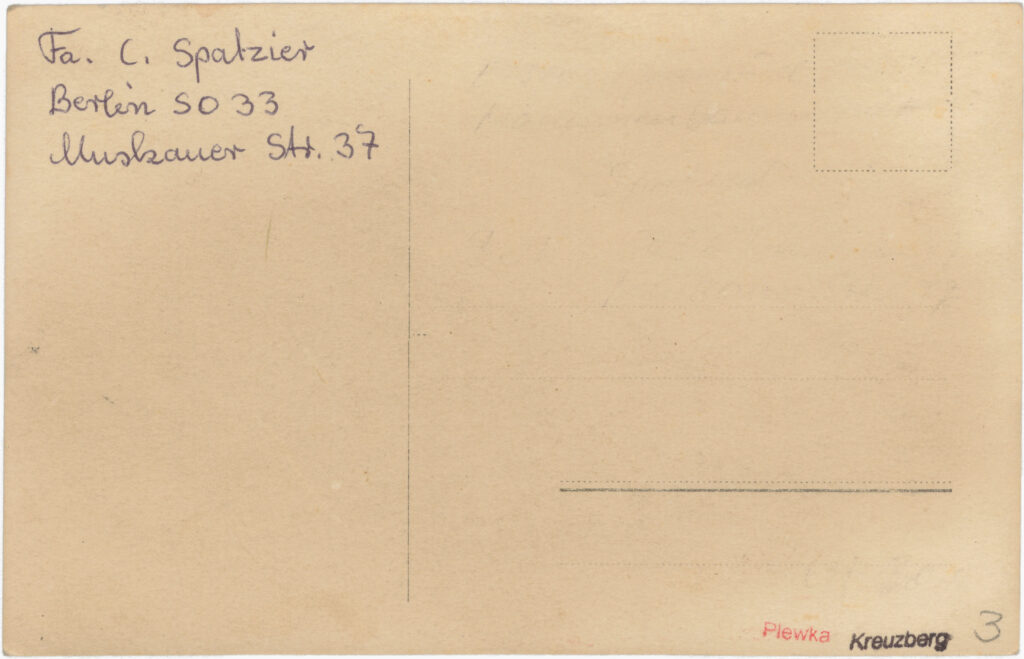

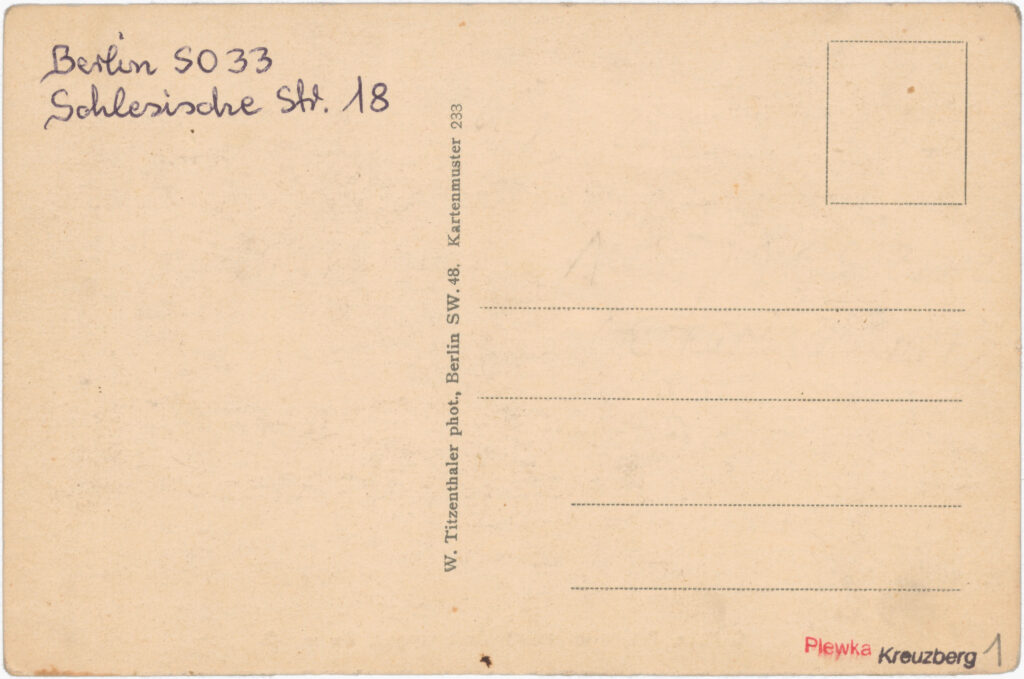

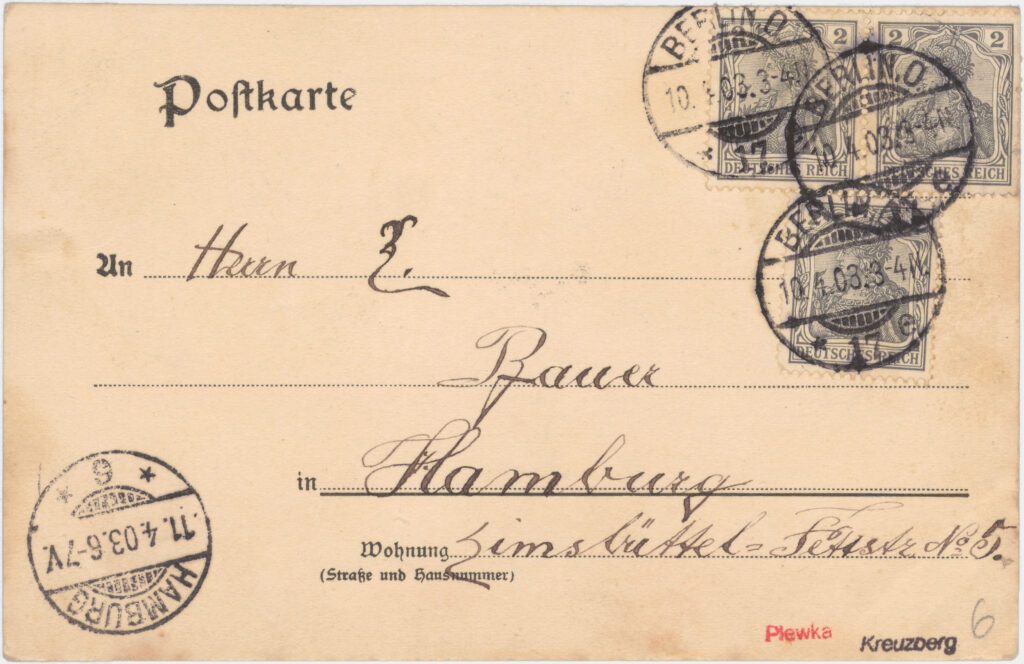

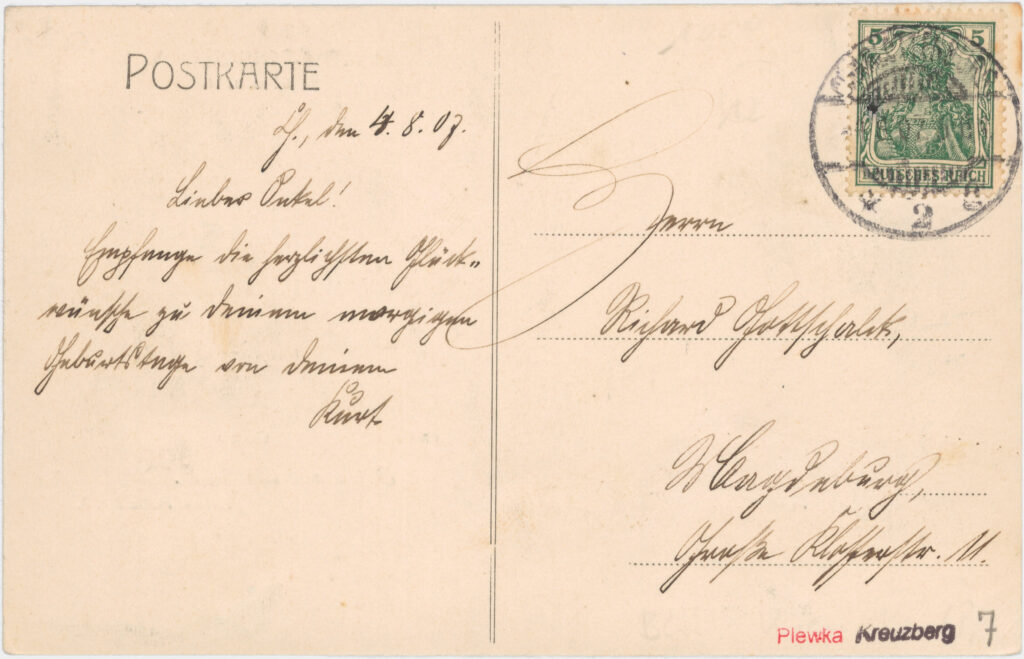

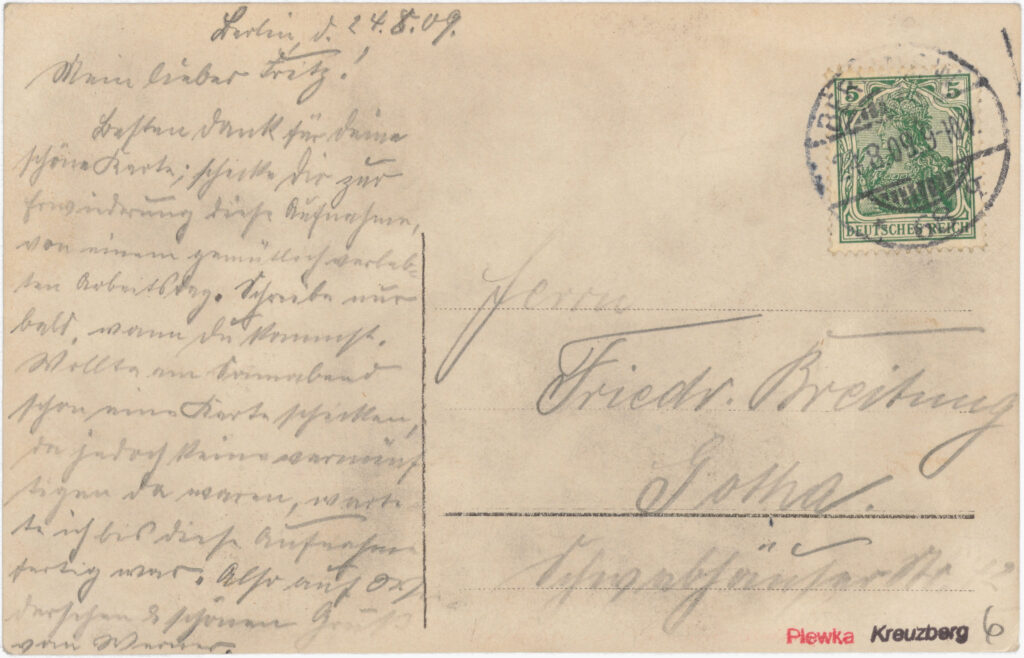

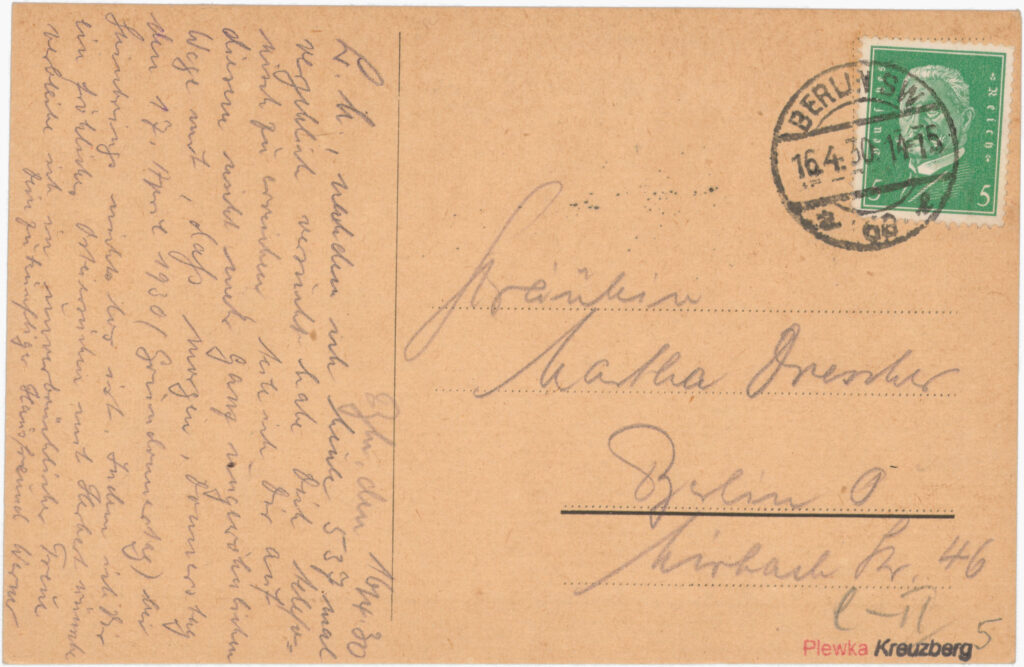

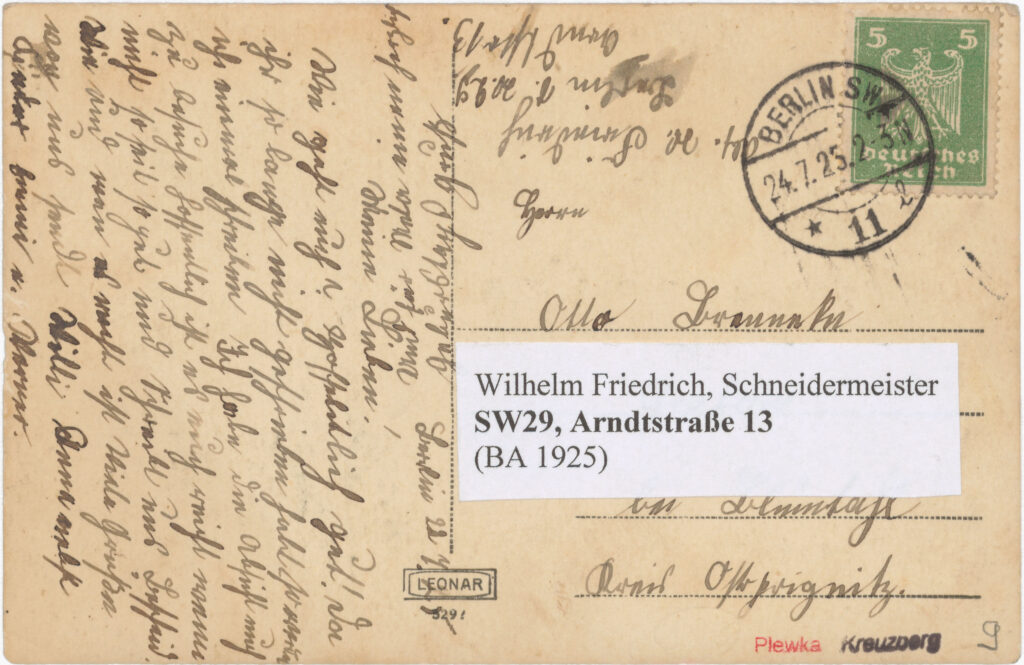

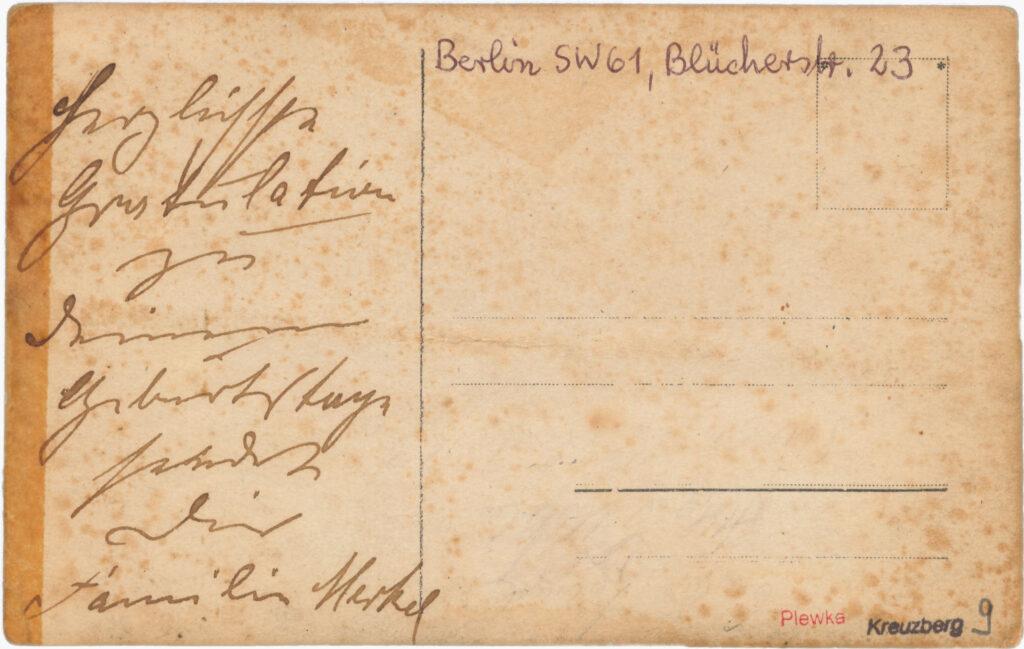

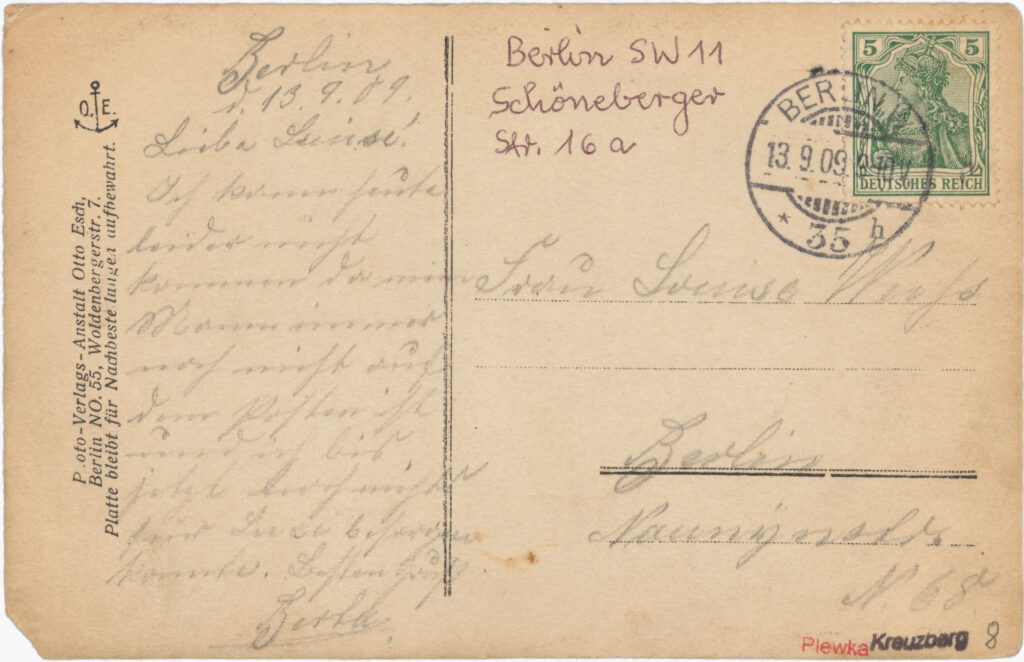

Whether operators of grocery stores or glassworks, workshops, coal shops, or factories, whether hairdressers, transport companies, or merchants: at the beginning of the 20th century, they all had their photographs taken in front of, or sometimes even inside, their businesses. They used the new medium of postcards as an advertising tool, posing as guarantors for the good quality of their products or services. They often also used the cards to send personal messages or for commercial communication.

Dozens of postcards from Kreuzberg shops, craft businesses, and industries are part of Peter Plewka’s collection. Occasionally, these photographs were commissioned works, but mostly they were casual shots by street photographers who roamed from house to house with their cameras, offering their services spontaneously. Far away from major events and tourist attractions, these postcards highlight work and everyday life, which, during the postcard boom around 1900, were considered worthy for remembrance and communication.

Today, these postcards also offer insights into the specific combination of living and working that long shaped the Kreuzberg cityscape, what we now call “mixed-use neighborhoods”.

“This is Our Shop”– Postcards and the Pride in One’s Own Business

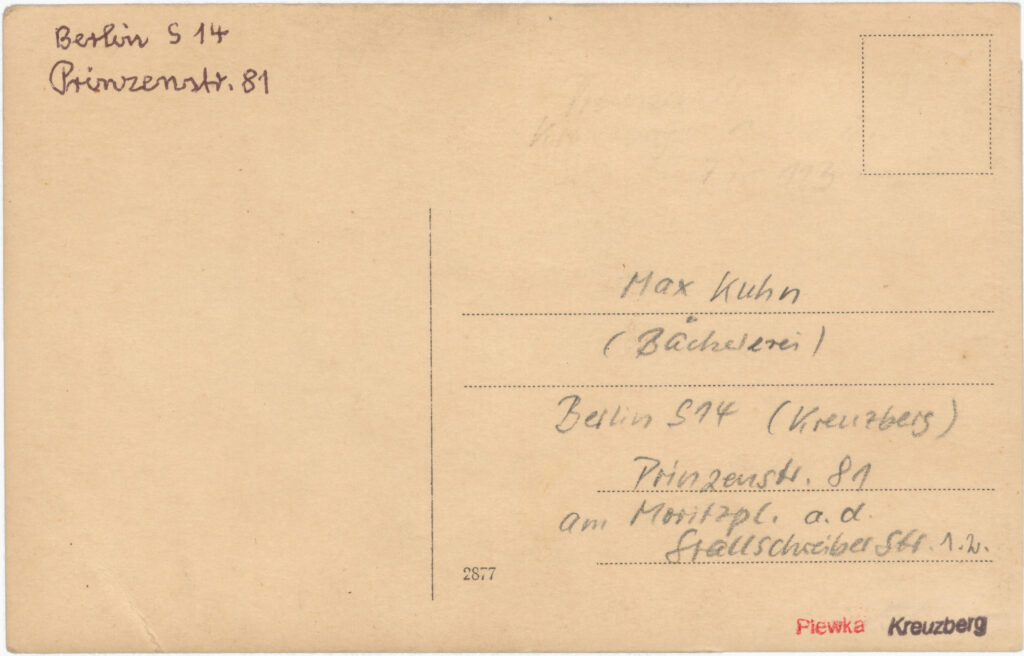

In the ground floors of many Kreuzberg tenement houses, small shops or craft businesses were located around 1900. Images of business owners and employees in front of these shops – sometimes in pairs, sometimes in groups of four or twelve – are among the key motifs in Peter Plewka’s collection. Often, the postcards were used to officially promote the business and its offerings. However, they were more commonly used for private purposes. This is evident from postcards that the depicted individuals sent to friends or family members, typically with short-term messages. In doing so, they referenced the image and, with a certain pride, drew the recipients’ attention to their own business.

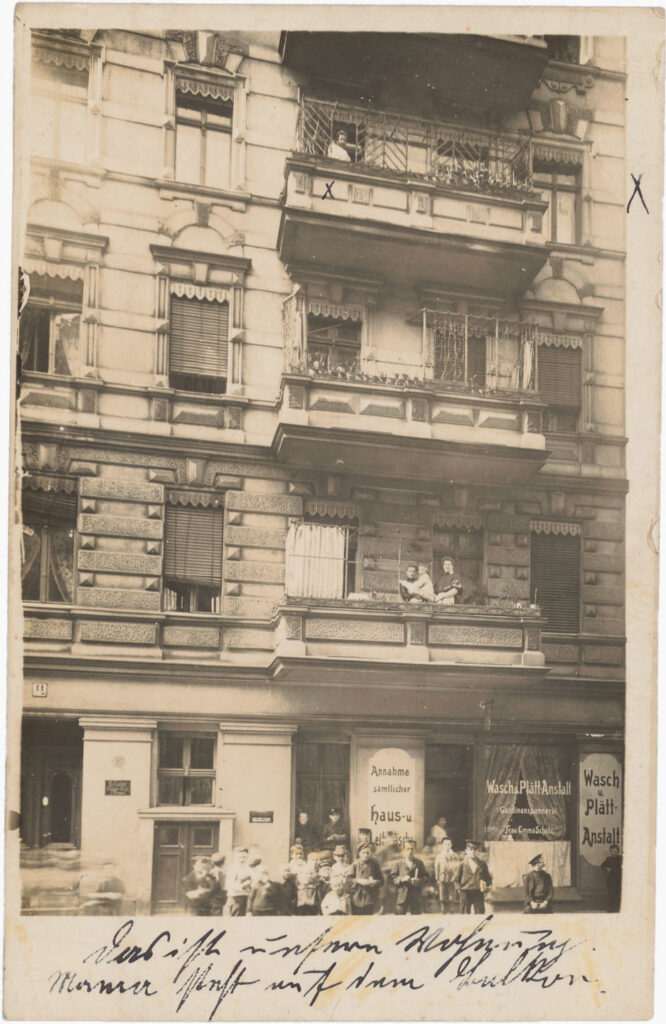

“This is Our Apartment, Mama is Standing on the Balcony” – The Coexistence of Living and Working

While businesses were often located on the ground floors of Kreuzberg tenement houses, the upper floors were used for living. Business owners and other residents of the building were frequently photographed together. The low quality, perspective, and framing of many of these images suggest that the photographers took them quickly and without much planning. However, one effect of this was that the postcards became affordable and accessible to many people. As a result, they served as mementos and as a popular medium for private communication, both within and beyond the city.

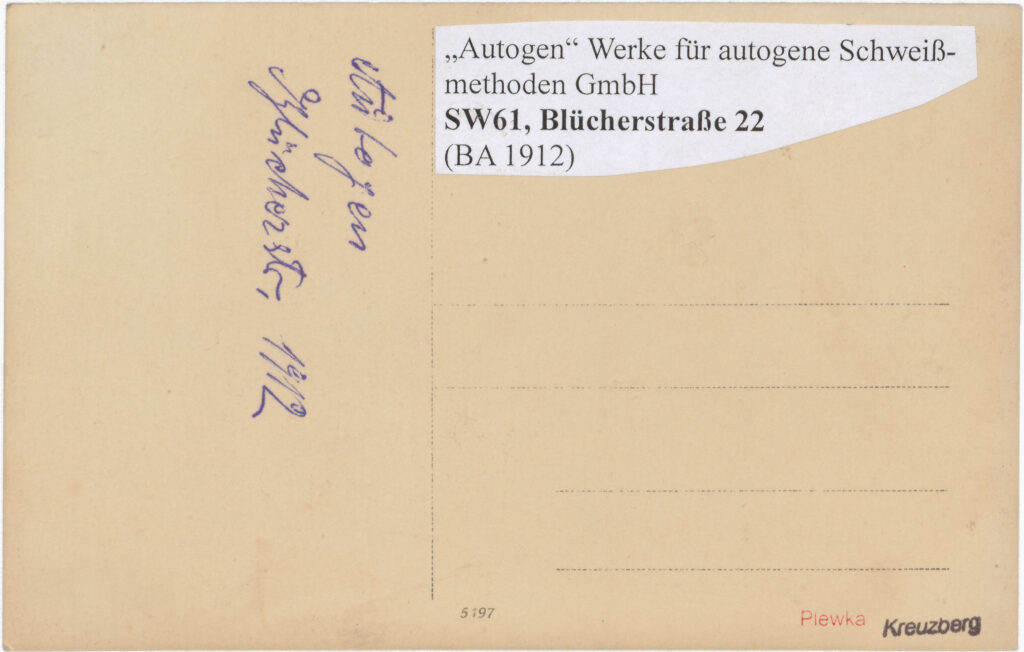

Workforces – Employees at the Heart of Industry and Trade

With the advancing industrialization at the end of the 19th century, larger enterprises increasingly emerged in Kreuzberg. Often, these companies commissioned photographs and postcards for self-presentation, which were all similarly composed: employees––and in some cases also female employees––posed in work attire in front of their workplaces. Youngsters sat at the front on the floor, while the owners stood out from the rest of the workforce through their clothing and positioning in the image. Work products and tools indicated the type of business, and a sign with the company name was usually prominently displayed in the center.

Such images served externally to portray a well-organized, thriving, and productive company. By focusing on the employees––rather than on the production facilities and machinery––these images also served an integrative function internally.

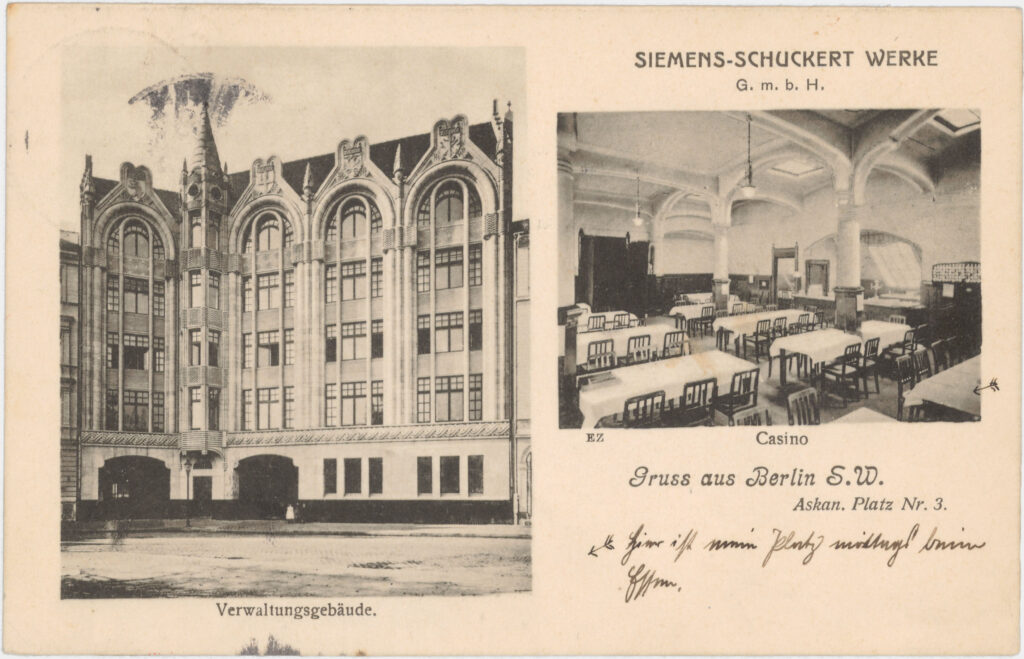

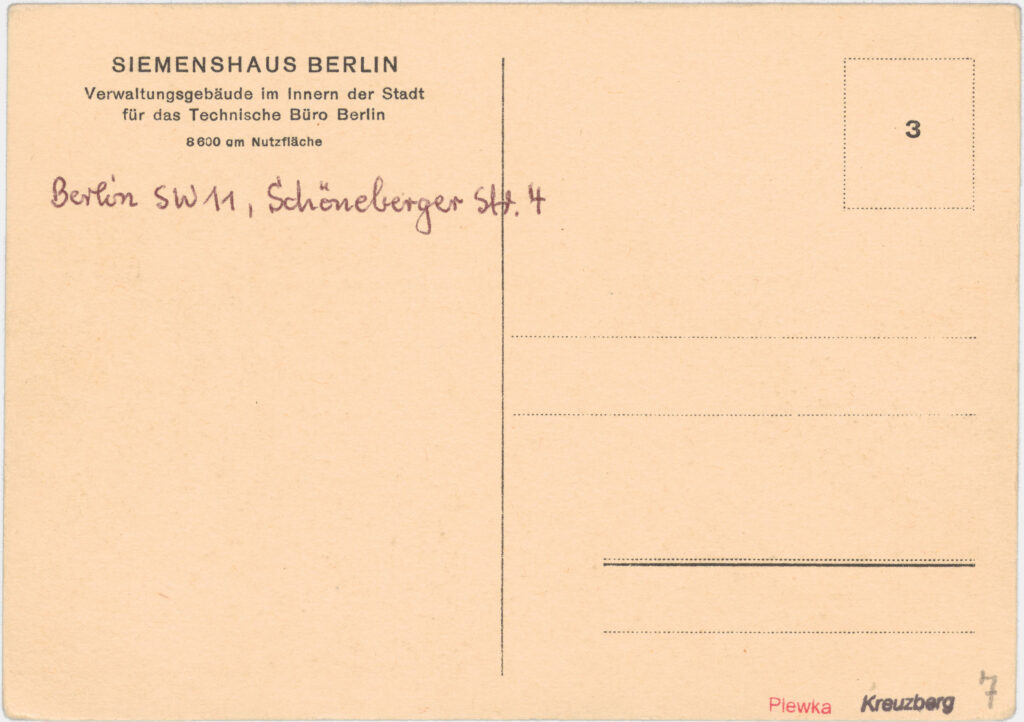

Siemens & Halske – A Global Corporation from Kreuzberg

Shortly after the turn of the century, the first administrative building of Siemens & Halske was established at Askanischen Platz near the Anhalter Bahnhof. By this time, the company, which had been founded in a Kreuzberg backyard, had risen to become a global leader in the electrical industry. Around the same period, construction began on Siemensstadt in Spandau, where the previously scattered production facilities were relocated. Siemensstadt was also complemented with a residential area for workers. In 1913/14, the main administration moved from Kreuzberg to Spandau, leaving only a small, newly constructed administrative building for public traffic in Kreuzberg.

In Peter Plewka’s collection, there are no postcards of Siemens & Halske that, like many other businesses, focus on the workforce. Instead, the preserved postcards primarily showcase the company’s founder, its technical inventions, or its modern administrative buildings.

These postcards were occasionally used by employees to greet acquaintances or relatives and to highlight their workplaces.

”In This House, I Waste My Mind”– Employees and Their Attitude Towards Work

The less staged photographs in front of shops or businesses offer small insights into the relationship between Kreuzberg’s workers and their labor. When employees, for example, pose playfully or casually in front of their store, it could be interpreted as a sign of distance from the business, or as an attitude where they do not want to appear overly committed. This becomes clearer in the rare cases where employees themselves evaluate their work on postcards.

![“Miss Meta Voll Mrs. General Senior Physician Pful Hanower Schiffgraben 10 Berlin, 19/10/09. Dear Meta, I’m sending you a view of our shop. Hopefully, you are still at your position. Many greetings from Martha Manzke. [At the edge:] please respond??? Sender: Martha Manzke // Berlin S Hasenheide 4 P.” “Conditorei u. Café Emil Krüger", Hasenheide 49, no date (sent on 19.10.1909), SPP / FHXB 1843.](https://sammlung-plewka.friedrichshain-kreuzberg-museum.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/handel-2-1843v-671x1024.jpg)

![“Miss Meta Voll Mrs. General Senior Physician Pful Hanower Schiffgraben 10 Berlin, 19/10/09. Dear Meta, I’m sending you a view of our shop. Hopefully, you are still at your position. Many greetings from Martha Manzke. [At the edge:] please respond??? Sender: Martha Manzke // Berlin S Hasenheide 4 P.” “Conditorei u. Café Emil Krüger", Hasenheide 49, no date (sent on 19.10.1909), SPP / FHXB 1843.](https://sammlung-plewka.friedrichshain-kreuzberg-museum.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/handel-2-1843r-1024x659.jpg)