- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

Technology & Faith in Progress

The end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century was a concentrated period of technological innovations that transformed what is now Germany into an industrial society. The systematic connection of science and technology led to numerous new achievements and an explosive expansion of industry. In the early 20th century, more and more people from near and far, and often from rural areas, were drawn to cities. This not only changed the lives of people who had previously lived in villages, small towns, and suburbs, but also necessitated the redesign of cities to provide housing, transportation, and consumer goods for the growing population. Against the backdrop of industrialization, the modern metropolis emerged, with Berlin becoming a leading city in terms of technical innovations and urban planning.

For example, the development of internal combustion engines paved the way for the automobile, while electricity was simultaneously exploited as a propulsion. The electrification of streetcars, the commissioning of Germany’s first electric elevated and underground railway, and the introduction of artificial street lighting significantly shaped Berlin’s appearance. Technological innovations not only permeated factories and production but also the daily lives and leisure activities of people. Large department stores like Karstadt at Hermannplatz became symbols of the consumer society, turning into “cathedrals of modernity.” Mass media, such as postcards, became very popular and reflected key features of a rapidly modernizing world: economic rationality, speed, novel visual communication, and communicative participation. This is made evident in the Peter Plewka Collection and the selected motifs presented here.

Thus, the technological progress of this era fostered widespread optimism and a strong belief in humanity’s ability to continuously improve living conditions through science and technology. It also reinforced a colonial European self-perception that technological progress sprung from the Western imperial world and served to “civilize” the rest of the world.

The belief in progress was not universally endorsed. While many welcomed the positive effects of technology and industrialization, there were also voices that were concerned about their potential for threat and destruction. They pointed to the formation of a modern class society or condemned the oppression and exploitation of people in the colonies. In Berlin, both modern and traditional elements coexisted: horse-drawn carriages and automobiles shared the streets, while steam locomotives continued to operate despite electric streetcars. This juxtaposition of new and old technologies shaped the development of living conditions in the metropolis of Berlin.

The modern metropolis, with its technical innovations and urban architecture, is depicted on several postcards in the Plewka Collection. For today’s viewers, they convey an image of a progressive city.

Berlin Electrified - Electric Public Transport

At the end of the 19th century, Berlin experienced unprecedented population growth due to industrialization, its designation as the capital of the Reich, and the incorporation of surrounding areas. The prospect of work attracted many people and led to new challenges in public transportation. Horse-drawn and steam trains could no longer handle the load, and new technologies were sought.

In 1879, the Siemens company garnered significant attention with the first practical electric locomotive and the vision of an electric railway over the rooftops of Berlin. Initially, this idea was ridiculed and met with skepticism. Experts doubted its feasibility, while citizens demanded decorative and artistic construction of the stations.

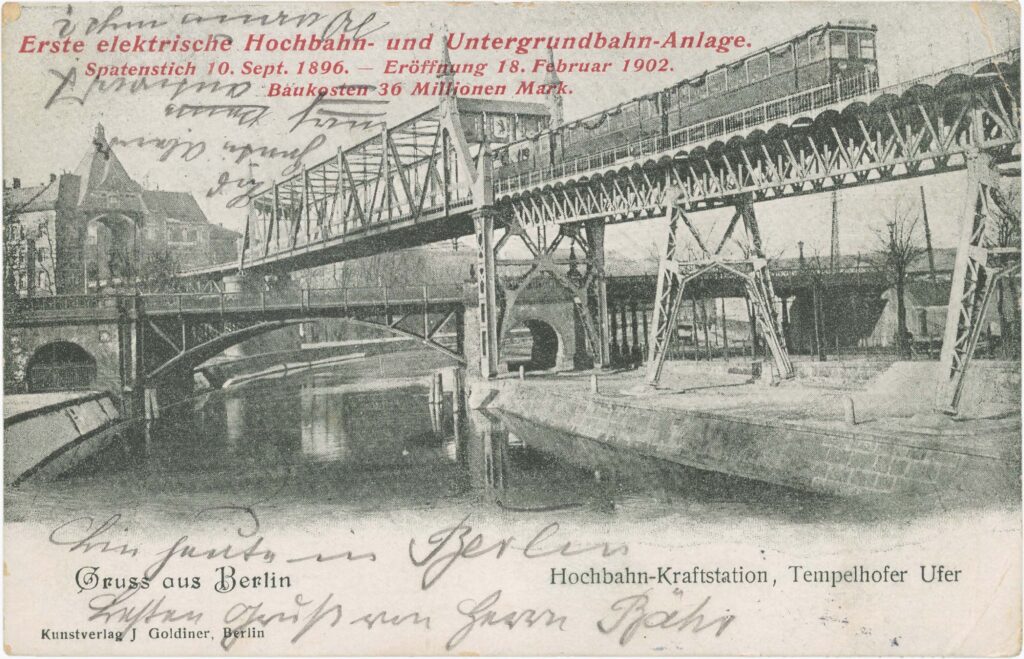

Nevertheless, Siemens persisted over the years and began constructing the core line, today’s U1/U2 line, in 1896. With its opening in 1902, it became the first electric elevated and underground railway in what is now Germany and was considered an engineering masterpiece.

The construction and inauguration were also the subject of postcards, as seen in an example from the Plewka Collection. The dates and reference to the first electric railway system seem to positively affirm the modernization; at the same time, it is unclear whether the printed reference to the construction cost of 36 million Mark might be a critique.

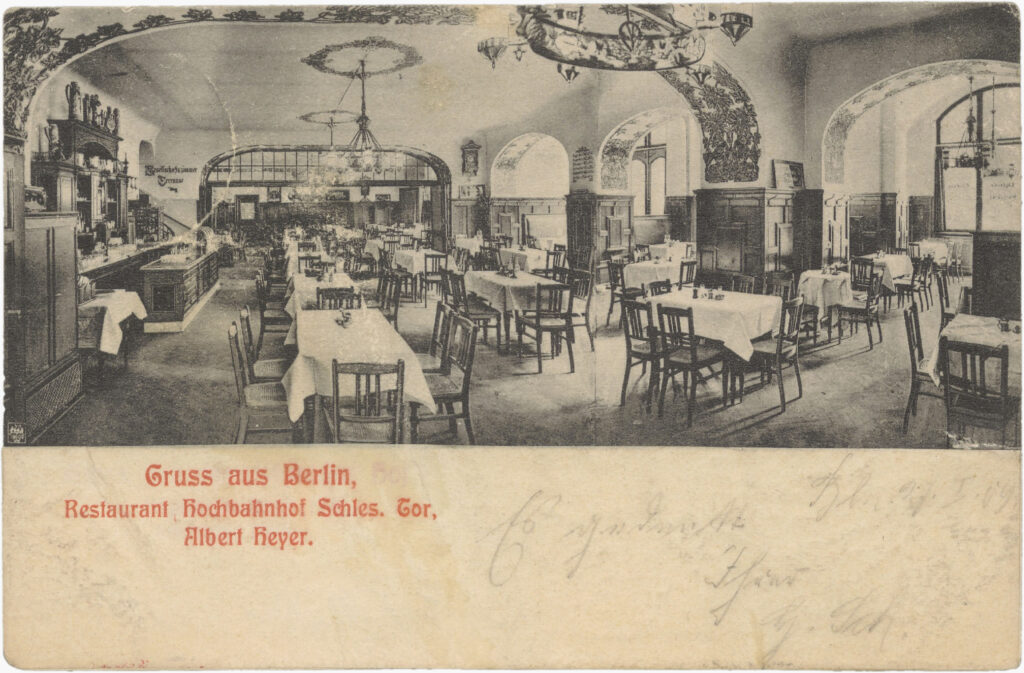

SCHLESISCHES TOR

The Schlesisches Tor elevated railway station was designed with historicizing elements in architecture and façade, according to the stylistic preferences of the time. As an important point of departure for boat trips on the Spree River, it was intended to be particularly representative and inviting. The interiors offered a café and a restaurant with a bowling alley for Spree excursionists.

Quane Martin Dibobe

In the German Empire, there were very few places where Black people held everyday jobs; the employment of a Black man like Quane Martin Dibobe at the Berlin elevated and underground railway was unusual at the time.

Dibobe, the son of an influential family in Cameroon, came to Germany in 1896 as part of the First German Colonial Exhibition, which opened that year along with the first Berlin Trade Exhibition in what is now Treptower Park. He was part of a group of 106 people, mostly from German colonies, who were discriminatively displayed as supposed “primitives” in front of a million people in a “human zoo”. After the exhibition, Dibobe—like about 18 other individuals—remained in Berlin, completed an apprenticeship as a locksmith, and from 1902 to about 1919, worked primarily as a train conductor for the Berlin elevated railway. He was also politically active. After the end of the Empire, he and 17 other Africans submitted a 32-point petition—the so-called Dibobe Petition—to the Weimar National Assembly in 1919, demanding equal rights for people in and from German colonies, an end to colonial violence, and political participation for Black people in the colonies. Shortly after they submitted the petition, the Treaty of Versailles came into force, under which Germany lost its mandates in colonized regions. In 1921, Dibobe sought to move with his family from Germany to Cameroon, but entry was denied by the French colonial authority. It is believed that the family traveled to Liberia, but their their trace disappears, and no further information on their lives is known.

A few photographs of Dibobe as a member of the transportation company still exist today. The postcard in the Plewka Collection, where he is depicted, suggests that his presence was seen as something of a sensation that should satisfy the public’s curiosity.

'Cathedrals of Modernity' -

Hermannplatz & Karstadt

Technical innovations not only greatly influenced the modernization of production sites but also impacted people’s everyday lives with the emergence of the consumer society and the concept of leisure. Department stores can be seen as a field directly linked to technological innovations and the development of goods; they invited people not only to shop and consume but also to stroll and observe. As highly frequented places in the city, they even became “cathedrals of modernity.”

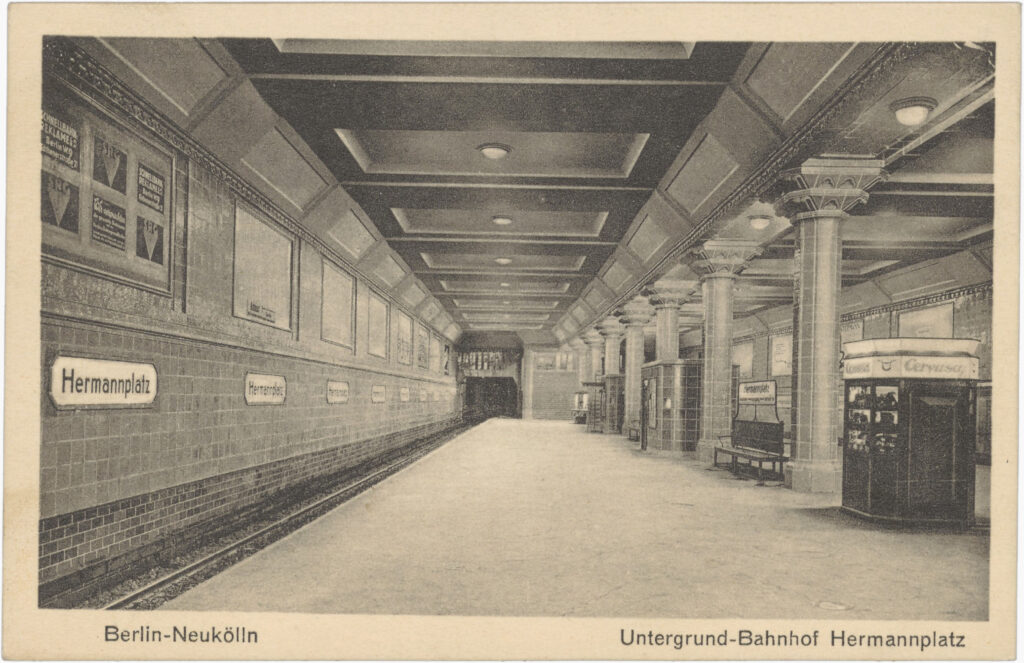

In the 1920s, Hermannplatz developed into an important transportation hub in southeastern Berlin, designed to meet the needs of the growing city and its working population. The planned redesign of Hermannplatz, the construction of the underground station, and the planned department store of Karstadt AG were conceived together from the beginning and were also built simultaneously. The station complex under Hermannplatz was thoughtfully planned, spaciously designed, and offered modern architectural solutions such as an underground connection to the department store and escalators to facilitate transfer traffic. When the Karstadt building opened in 1929, it was the largest department store on the European continent.

In the Plewka postcard collection, there are several motifs depicting the urban modernization of Hermannplatz above and below ground. It is noticeable that the depicted motifs convey an impressive size and spaciousness, contrasting with the narrow tenement blocks of the 19th century in the surrounding quarters, where predominantly workers lived.

Author

Marcel Ravens

MA Public History

LITERATURE

Axster, Felix: Koloniales Spektakel in 9 x 14. Bildpostkarten im Deutschen Kaiserreich. Bielefeld 2014. Transcript.

Bohle-Heintzenberg, Sabine: Architektur der Berliner Hoch- und Untergrundbahn. Planungen, Entwürfe, Bauten bis 1930. Berlin 1980. Willmuth Arenhövel.

Dame, Thorsten (Hg.): Elektropolis Berlin. Architektur- und Denkmalführer. Petersberg 2014. Michael Imhof Verlag.

Dienel, Hans-Liudger/Schmucki, Barbara (Hg.): Mobilität für alle. Geschichte des öffentlichen Personennahverkehrs in der Stadt zwischen technischem Fortschritt und sozialer Pflicht. Stuttgart 1997. Franz Steiner Verlag.

Düspohl, Martin (KreuzbergMuseum) (Hg.): Kleine Kreuzberggeschichte. Berlin 2012 (1. Aufl. der Neuauflage). Berlin Story.

Elkins, Thomas Henry/Hofmeister, Burkhard (Hg.): Berlin. The spatial structure of a divided city. London 1988. Methuen.

Fraunholz, Uwe/Woschech, Anke (Hg.): Technology Fiction. Technische Visionen und Utopien in der Hochmoderne. Bielefeld 2012. Transcript.

König, Wolfgang/Landsch, Marlene (Hg.): Kultur und Technik. Zu ihrer Theorie und Praxis in der modernen Lebenswelt. Frankfurt am Main 1993. Peter Lang Verlag.

Matthews-Schlinzig, Marie Isabel/ Schuster, Jörg/Steinbrink, Gesa/Strobel, Jochen (Hg.): Handbuch Brief. Von der Frühen Neuzeit bis zur Gegenwart. Berlin/Boston 2020. De Gruyter.

Scarpa, Ludovica: Martin Wagner und Berlin. Architektur und Städtebau in der Weimarer Republik. Wiesbaden 1986. Vieweg+Teubner Verlag.

Whyte, Iain Boyd/Frisby, David: Metropolis Berlin: 1880–1940. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London 2012. University of California Press.