National Socialism in

Everyday Life in Kreuzberg

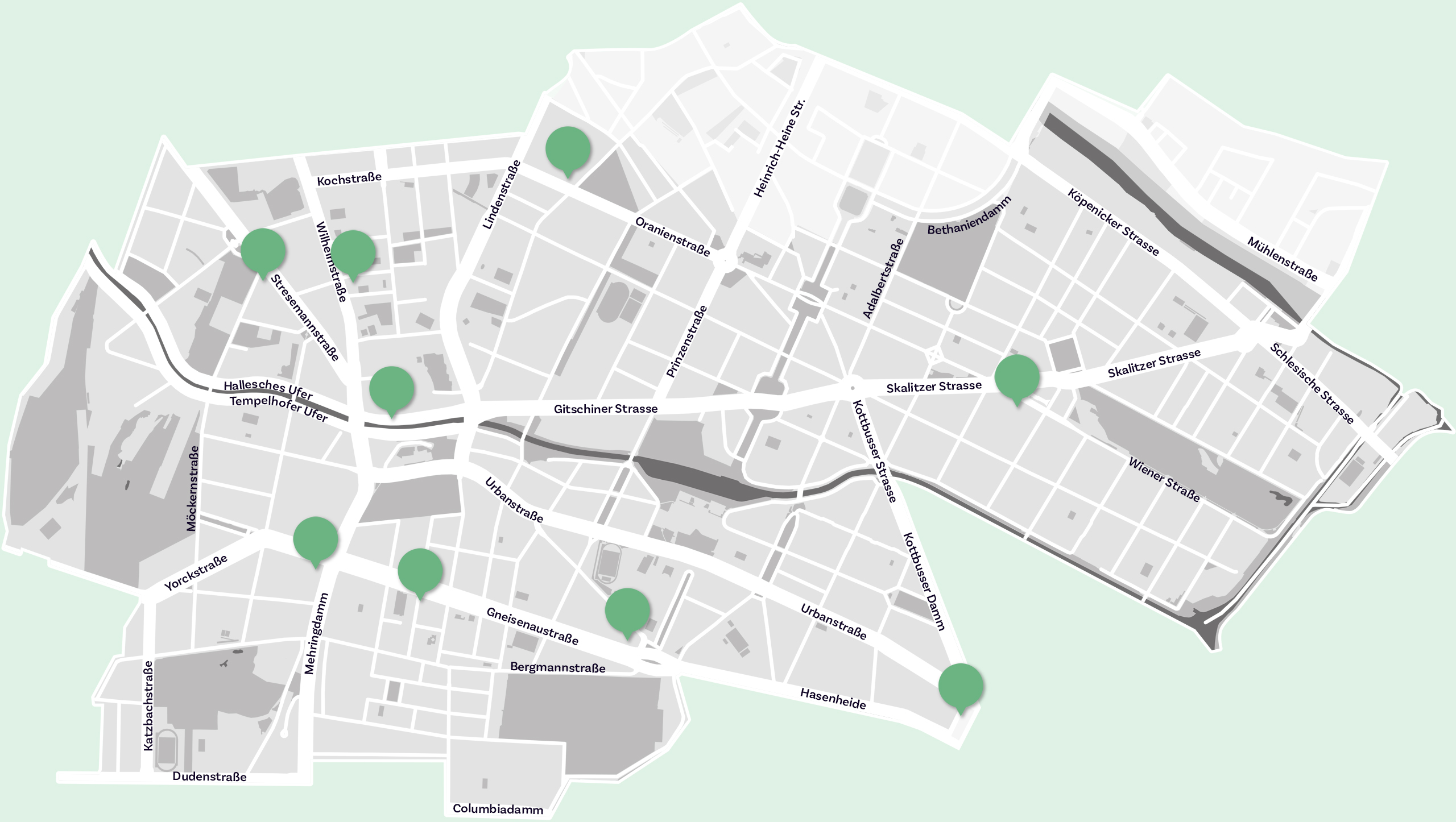

In Kreuzberg, March 10, 1933 dramatically symbolized the violent end of democracy: Together with other members of the district office and representatives, the Jewish mayor of Kreuzberg, Dr. Carl Herz was forcibly chased by the SA (the so-called “Storm Division” of the National Socialists) from the town hall on Yorckstraße to Marheinekeplatz. This brutal event marks the beginning of the handover of legitimate power to the National Socialists in Kreuzberg, which continued the prior terror and violence of the National Socialists.

The collection of Peter Plewka includes postcards from this period that provide insight into Kreuzberg under National Socialism. Particularly striking are those postcards that show National Socialist symbols such as the swastika flag or are franked with stamps bearing Hitler’s likeness. Other cards capture snapshots of celebrations such as May Day or the Day of National Mourning.

However, National Socialist terror remains invisible on these postcards. Sites of oppression, torture, and murder are not found in Peter Plewka’s collection. One place that represents the brutality of the NS regime more than any other is the Reich Security Main Office – the Gestapo headquarters – on Prinz-Albrecht-Straße 8. The collection only includes postcards showing this building as an arts and crafts school during the time before the Nazis used it.

At first glance, the postcards depict little of what happened in Kreuzberg during National Socialism, especially concerning the regime of terror and violence. However, they do allow for the illumination of individual aspects of Kreuzberg under the swastika and show which images were supposed to be created by the propaganda during this time.

Banners and Flags on Kreuzberg Streets

The swastika was one of the most important and is to this day the most powerful symbol of National Socialism. It appeared on many banners and flags and played a prominent role in the presence of National Socialism in everyday life. The swastika flag became a symbol representing the racist, anti-Semitic, and chauvinistic policies and practices of National Socialism and was part of everyday public propaganda. The mass visibility of the swastika was also a strategy to constitute society in terms of a community designed by racism.

The swastika flag was always present in public places, as well as at events and parades. Even in private spaces, flags were used to show loyalty and sympathy with the NS movement or the regime. Especially during national holidays, many citizens hoisted flags on their houses.

In propaganda films, images of such seas of flags were often shown, which are still mostly reused uncritically today.

“Diversity” of Flags

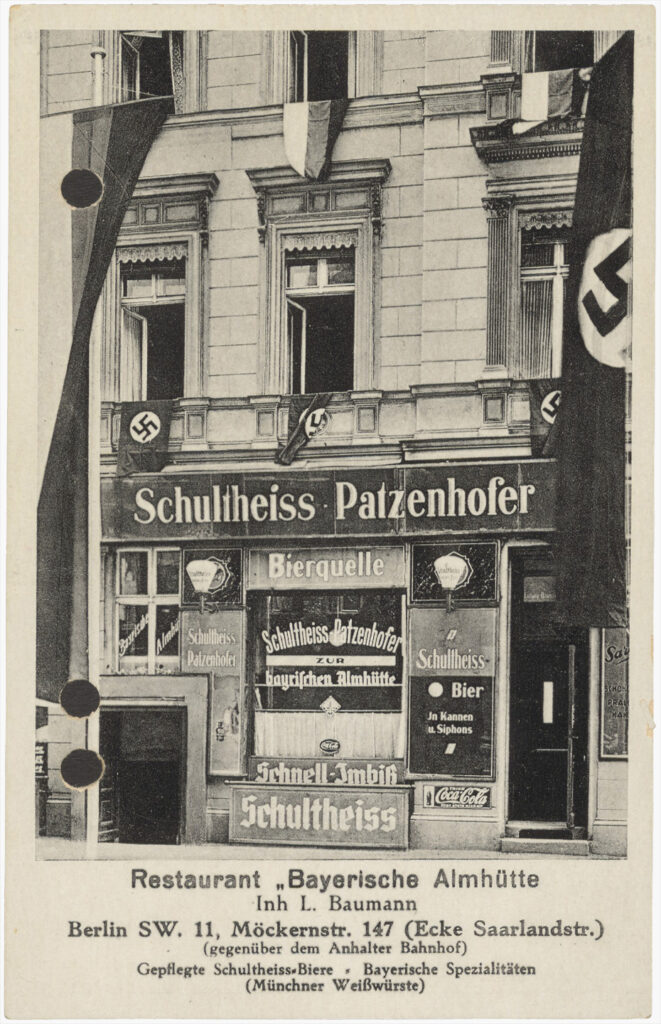

These postcards show a building at Gneisenaustraße 55/56 and the restaurant “Bayrische Almhütte” on Möckernstraße 147. Only upon closer inspection does one recognize the many flags. The juxtaposition of the black-white-red Imperial flag and the swastika flag suggests that the photos were taken between 1933 and September 1935, as both flags were used as national flags during this period.

Swastikas at Belle-Alliance-Platz (Mehringplatz)

This postcard shows the facades of houses 19 to 22 on Belle-Alliance-Platz (now Mehringplatz). The leaf garlands decorating the facades along with the flags indicate a holiday. It is also noteworthy that the card is creased on both sides, and the swastikas in the middle have been painted over. It is unknown who did this and for what reason.

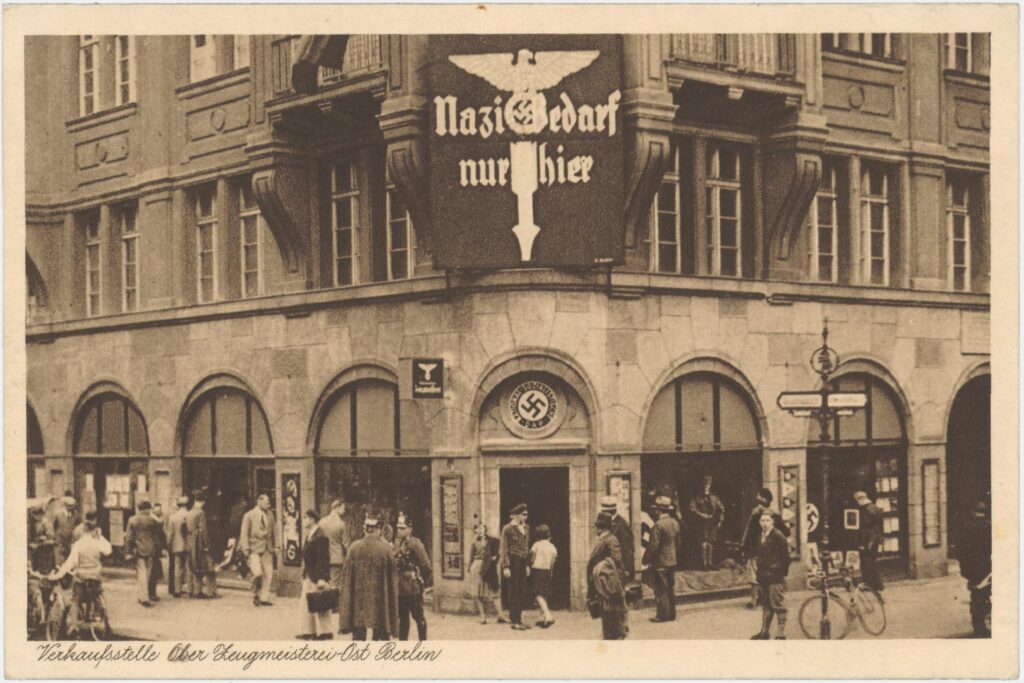

“Nazi Supplies Only Here”–

The Zeugmeisterei-Ost on Hedemannstraße 10

Hedemannstraße 10 was an important place for the National Socialists in Berlin. Since the late 1920s and confirmed from January 1, 1929, with the appointment of the first Reichszeugmeister in Munich, the Zeugmeisterei-Ost was located here. The Reichszeugmeisterei in Munich coordinated all “Zeugmeistereien” (quartermaster’s offices) in the Reich. SA members received their uniforms, equipment, and propaganda material there to ensure a uniform outfitting of the SA. A large number of tailor shops and craft businesses throughout the Reich produced for the Zeugmeistereien.

Since May 1, 1930, Hedemannstraße 10 was also the seat of various NSDAP offices for Berlin and Brandenburg and until April 5, 1932, the headquarters of the SA group Berlin-Brandenburg.

Particularly in the spring and summer of 1933, the entire Hedemannstraße was notorious and was often referred to as “the Hedemannstraße,” “Nazi barracks,” or “SA headquarters Hedemannstraße.” In house number 31, people were temporarily detained, tortured, and murdered. Such places are referred to as “wild concentration camps.” They served to intimidate and eliminate opponents immediately after the the handover of legitimate power to the National Socialists.

The Zeugmeisterei-Ost on the Postcard

On the front of the postcard, the Zeugmeisterei-Ost is called “the largest and oldest Zeugmeistereiof the N.S.D.A.P.” Since the Reichszeugmeisterei in Munich was the first NS-Zeugmeisterei, it is conceivable that the designation of the Zeugmeisterei-Ost as “oldest” refers to its possible previous function as an “SA economic office,” which had similar tasks.

Celebrations under the Swastika–

May 1 and Memorial Day

Celebrations during National Socialism aimed for a strong mass-psychological impact and were usually highly orchestrated. Almost all events were elevated to grand displays of the NSDAP and the propagation of a racially imagined community, accompanied by parades, consecrations, torchlight processions, and marches. These ritualizations of political life played an important role in the establishment of the totalitarian Führer state in the years 1933/34 and were part of comprehensive propaganda.

In April 1933, May 1 was declared the “Day of National Labor.” Already the next day — May 2, 1933 — trade unions were expropriated. Huge processions accompanied this day and were repeated annually to adopt the tradition of this originally socialist holiday and co-opt workers into the racially designed “Volksgemeinschaft” (national and racial community).

The National Socialists especially adopted the motif of commemorating victims for such ceremonies but repurposed it for their own ends. Thus, in 1935, they transformed the Memorial Day into “Heroes’ Memorial Day.” The focus shifted from mourning the dead to venerating heroes — in this case, the “heroes” of World War I. The propaganda impact of this day was so highly valued by the National Socialists that they scheduled decisive steps toward war preparations, such as the remilitarization of the Rhineland or the annexation of Austria, close to this day.

May 1, 1933, on Postcards

This postcard appears to be a snapshot of a march by the National Socialist Factory Cell Organization (NSBO) of Karstadt at Hermannplatz on May 1, 1933. It is clearly recognizable that the members of the NSBO — a National Socialist counterpart to the free trade unions — are being led by SA men. On May 2, they occupied the trade union buildings together with SA and SS.

The “Heroes’ Memorial Day” on the Postcard

The moment depicted on this postcard took place on February 25, 1934 — Memorial Day. It shows a celebration and wreath laying at the memorial of the Reich Printing Office. The following year, this holiday was also celebrated as Heroes’ Memorial Day. It is noteworthy that the description on the front of the card already refers to Heroes’ Memorial Day, possibly indicating that the card was produced the following year.

SA Storm Pubs in Kreuzberg

On November 19, 1922, the first local group of the NSDAP in Berlin was founded in the pub “Zum Reichskanzler” on Yorckstraße 90. The owners of such establishments, which were also considered transit premises for the National Socialists, often sympathized with the NSDAP or were themselves party members. From 1928, numerous “storm pubs” also emerged. These served as a base for an “SA storm” (comprising 72 to 240 members), from where the members would, for example, go out to brawl with political opponents or terrorize Jews. The pubs played a crucial role in the organization and mobilization of the National Socialist movement in Berlin.

In some venues, the SA ‘only’ occupied club and back rooms while normal public traffic continued. However, there were also storm pubs that almost completely gave up their character as public places, such as the pub “Zur Hochburg” of the so-called Storm 24 on Gneisenaustraße 17.

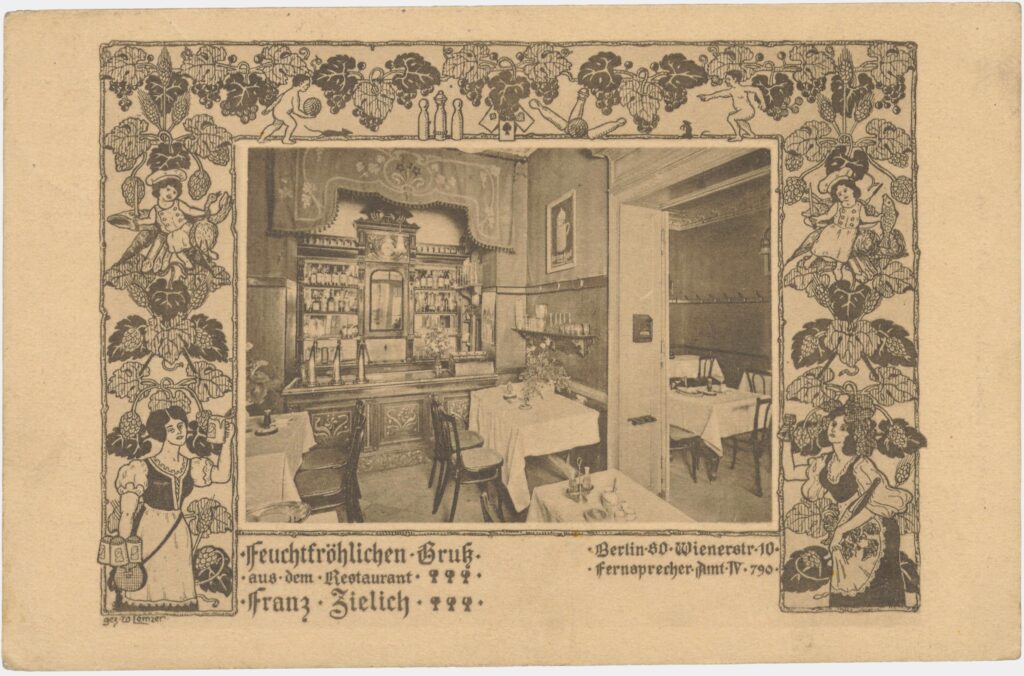

A particularly notorious storm and transit premise in Kreuzberg was the restaurant “Wiener Garten” on Wienerstraße 10. Already in February 1930, a regulars’ table society of this establishment defaced the synagogue on Kottbusser Ufer, today’s Fraenkelufer Synagogue, undisturbed for an hour.

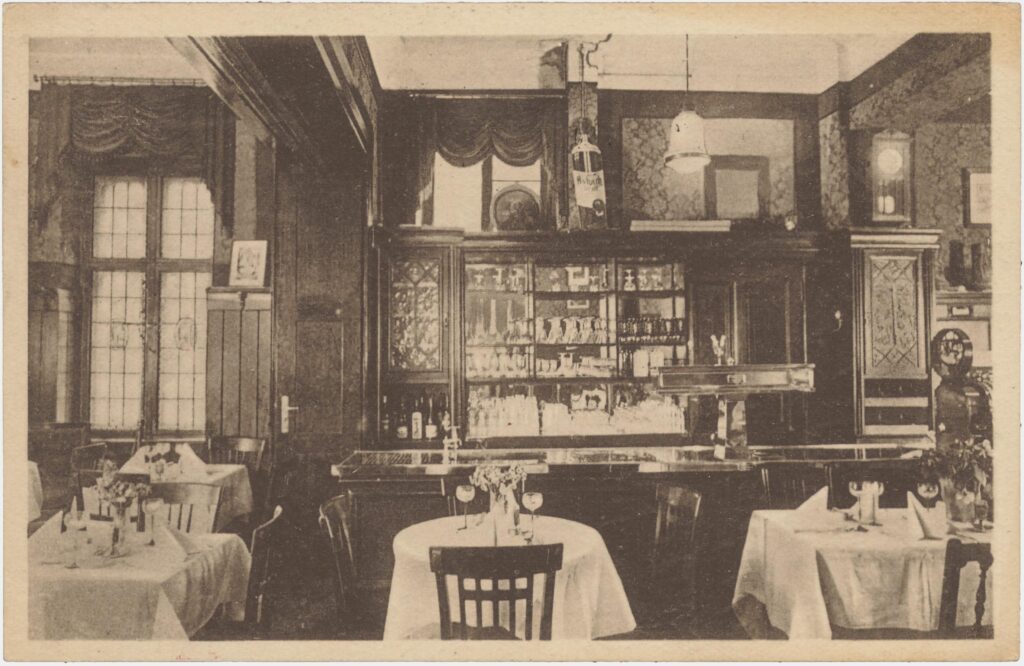

Insight into the Venue “Zum Reichskanzler”

The postcard shows the restaurant “Zum Reichskanzler” and is postmarked February 29, 1930. At this time, the establishment was already a transit premise of the NSDAP, which, however, is not evident from the postcard.

Insight into the “Franz Zielich” / “Wiener Garten” Restaurant

This postcard shows the restaurant “Franz Zielich” at Wienerstraße 10. Franz Zielich was the innkeeper of this establishment, which was later renamed “Wiener Garten.” The drawing of bowling pins on the card indicates a bowling alley. This was later converted into a meeting hall during its use as a storm pub.

Gneisenaustraße 17

This postcard from the years 1923/24 shows a photo of the “Berthold Redlich” pub at Gneisenaustraße 17, presumably depicting the owner and his wife. Later, this address housed the storm pub “Zur Hochburg,” whose entrance was guarded by SA men.

Author

Alexander Elspaß

MA Public History

LITERATURE

Brücker, Eva: Wohnen und Leben in SO 36, zum Beispiel in der Wienerstraße 10-12. In: Engel, Helmut/Jersch-Wenzel, Stefi/Treue, Wilhelm (Hg.): Geschichtslandschaft Berlin. Orte und Ereignisse, Band 5: Kreuzberg. Berlin 1994. Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung. S. 361-380.

Düspohl, Martin/Kreuzberg-Museum (Hg.): Kleine Kreuzberg-Geschichte. Berlin 2009. Berlin-Story-Verlag.

Fülberth, Johannes: »… wird mit Brachialgewalt durchgefochten«. Bewaffnete Konflikte mit Todesfolge vor Gericht, Berlin 1929 bis 1932/1933 (= Hochschulschriften, Bd. 87). Berlin 2012. PapyRossa Verlag.

Schuster, Martin: Die SA in der nationalsozialistischen »Machtergreifung« in Berlin und Brandenburg 1926–1934. Berlin 2004. Technische Universität Berlin.

Ueberhorst, Horst: Feste, Fahnen, Feiern. Die Bedeutung politischer Symbole und Rituale im Nationalsozialismus. In: Voigt, Rüdiger (Hg.): Politik der Symbole. Symbole der Politik. Opladen 1989. Leske u. Budrich. S. 157-178.

Verein zur Erforschung und Darstellung der Geschichte Kreuzbergs (Hg.): Kreuzberg 1933. Ein Bezirk erinnert sich. Berlin 1983. Ausstellungskatalog o. V.