- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

Working with Collections

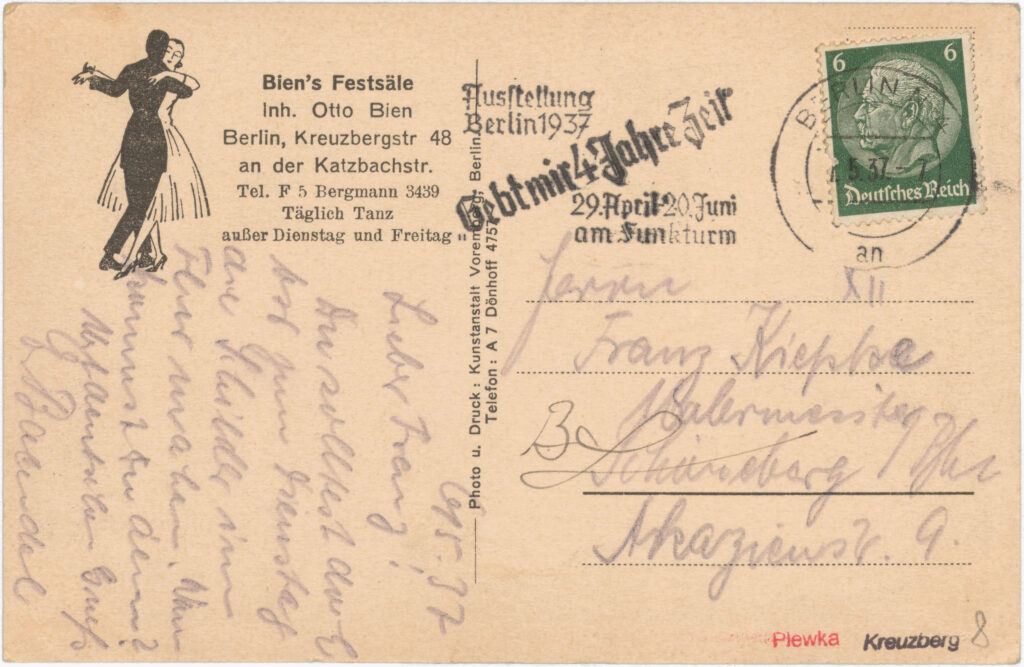

Peter Plewka’s collection of more than 5,600 postcards is unusual for the FHXB Museum in both its scope and organization. It differs from the existing museum collection by focusing on historical picture postcards and employing its own alphabetical system based on street names.

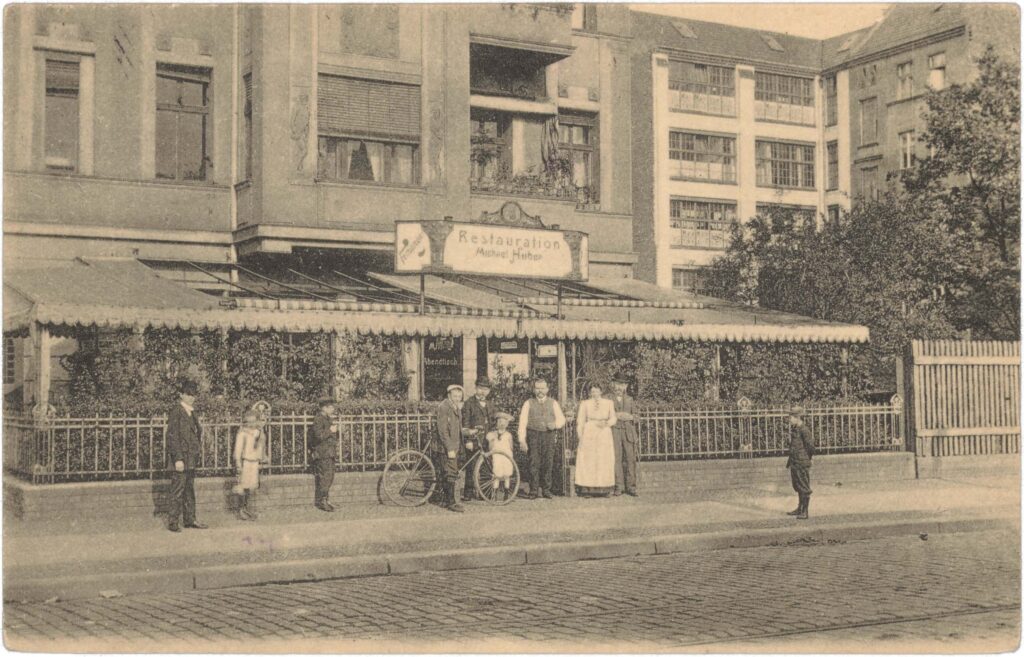

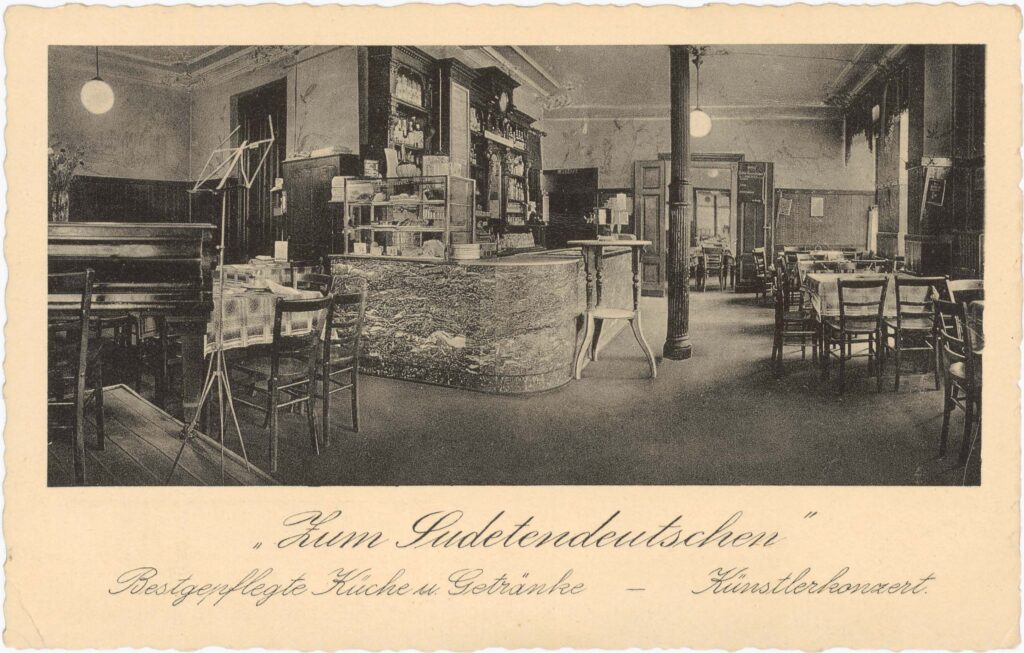

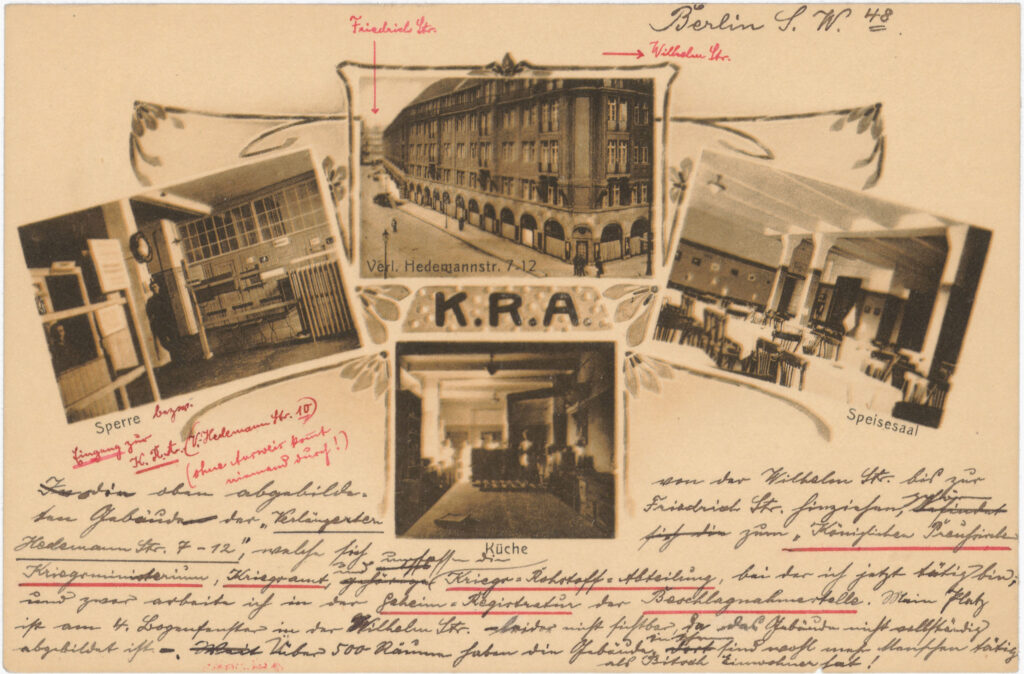

Many of the picture postcards are the only surviving images of certain locations in Kreuzberg, making them invaluable to the FHXB Museum. Since the collection includes not only views of tourist attractions but primarily non-representative house facades, ordinary streets, and local businesses, it offers insightful perspectives for researching and depicting everyday life in Kreuzberg.

Handling such new acquisitions raises questions about documentation, organization, use of the objects, and collecting practices. What do the postcards reveal about Kreuzberg during the period from around 1890 to 1945? What do they not show? Which social realities are made disproportionately visible, and which hardly or not at all? What focal points and gaps arise from this? How do museum visitors, researchers, and museum staff perceive the cards? Who was the collector? How did he search for and acquire his collection pieces? How did he select them? What was offered to him? How are postcards created in the first place?

Visual objects always emerge within sociopolitical contexts. The exploration of the Peter Plewka collection provides an opportunity to critically engage with visual objects like postcards and to investigate their complex histories.

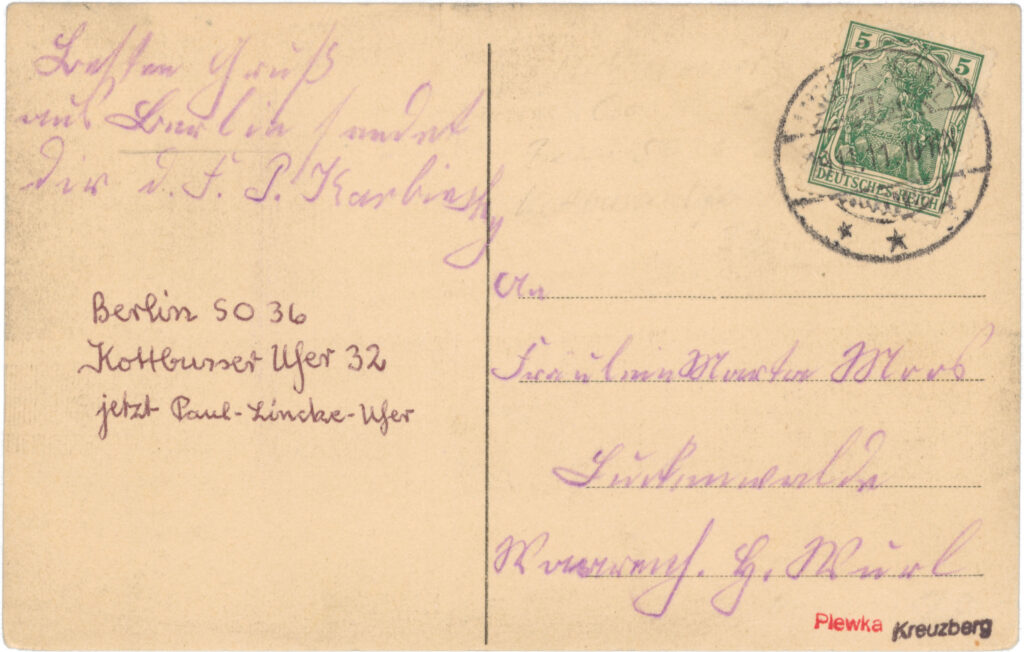

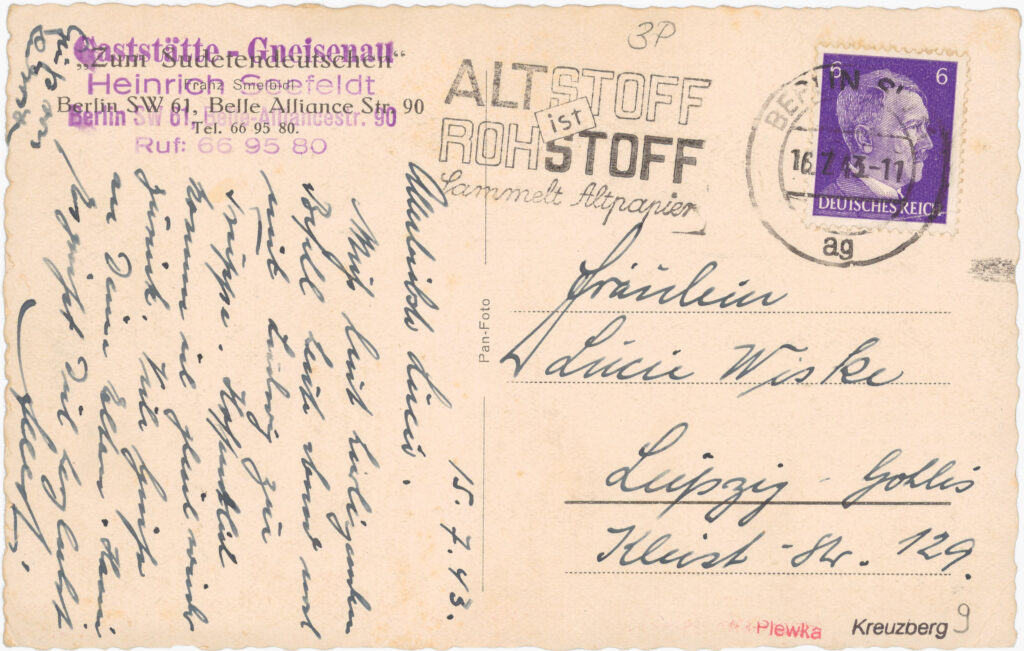

Peter Plewka organized his postcard collection alphabetically by street names and chronologically by years of production in albums. The FHXB Museum has preserved this organization but has transferred the collection to albums suited for archiving. On many cards, Plewka noted street name changes or changes in house numbers.

The Peter Plewka Collection in archival albums of the FHXB Museum.

Topographic Organization

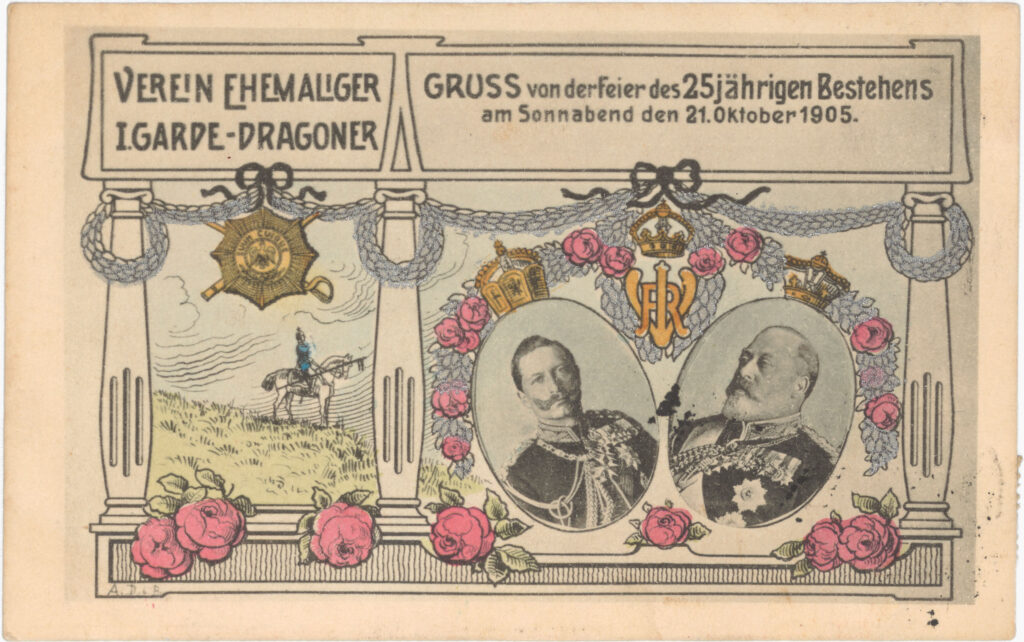

Plewka’s postcards are diverse in their dating, location, and image compositions. The collection spans from around 1890 to 1945, covering the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, and National Socialism.

Peter Plewka himself created a starting point for working with the collection by sorting the cards alphabetically by street names in albums. Here, the relevance of the location outweighed that of time or subject. We have maintained this emphasis. Shifting the focus would evoke different associations and ideas. Since some postcards lack information about the period of creation, we have approximated the dating by using clues in the images. The topographic order allows cards from very different phases and regimes to lie side by side, which we continuously reflect on while working with the collection.

Historical sources

Since their inception, picture postcard motifs have been regarded as historical sources. They were, and still are in some cases, considered testimonies of past life worlds. In the 1970s, research began to question the staging of such images. Questions about how these motifs contributed to normalizing, establishing, and stabilizing racist, fascist, anti-Semitic, and National Socialist power structures came into view. Increasingly, the contexts of production and the use of postcards are also being examined. Years, even decades, could pass between the capture of the motif, the production of the card, its inscription, its mailing, and its reception.

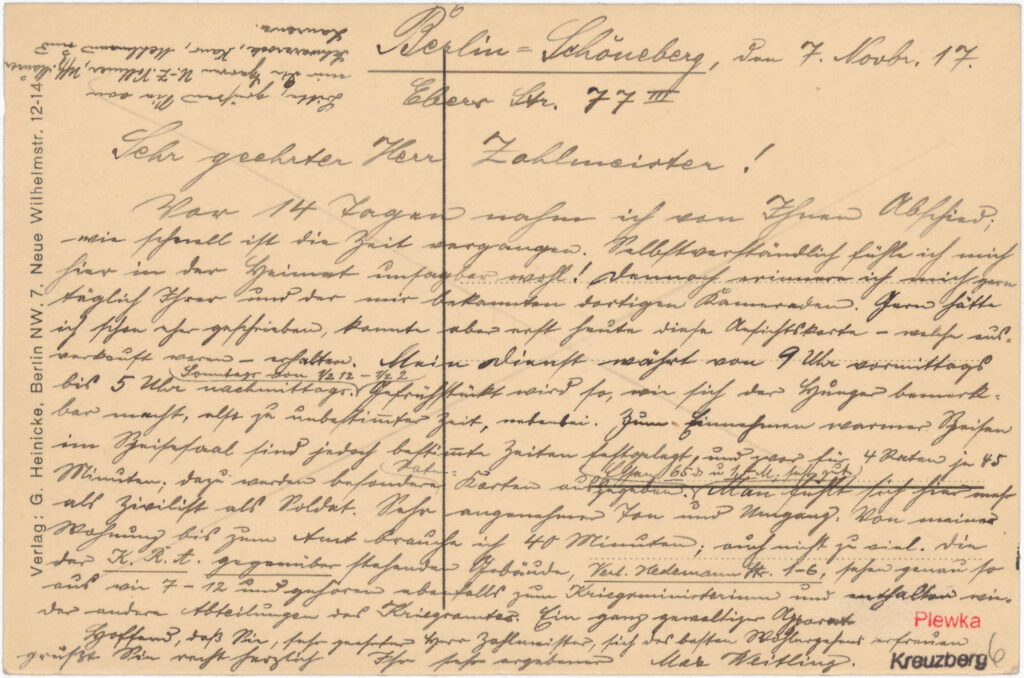

Each postcard offers two levels of text: printed inscriptions and handwritten messages. The printed text often reflects power relations, for example, in the naming of places or events while simultaneously omitting other depicted elements. Handwritten notes provide insights into individual use. Picture postcards were used by broad segments of the population, giving today a glimpse into the realities of people whose lives are usually undocumented, such as workers and women.

Mailing

Around 1900, picture postcards were a common means of communication, passing through many hands. Various actors and conditions influenced each card, from the selection of the motif to the mailing. The respective sociopolitical context is evident in handwritten texts, but also in stamps and postmarks.

Retouching and Montage

Motifs on picture postcards are problematic as documentary sources: The images were usually staged and often manipulated afterwards or even collages of different images. However, around 1900, at the peak of the picture postcard era, users were aware of this.

Staged vs. Casual

The creation of motifs on picture postcards varied greatly. Some were deliberately composed, for example, for advertising or staging purposes, featuring crafted, embellished image compositions and artistic design. Other motifs appear spontaneous, created in passing, or even as defective products.

Manufactured Power

Picture postcards are embedded within specific power structures. Their motifs regularly include elements and symbols that are casually or subtly depicted in the background of the image. As a result, these motifs convey, manifest, and normalize ideologies, regimes, and power relations.

Individual Appropriation

Picture postcards were used as everyday items, but the inscriptions and mailing altered the images. Often, writing was not limited to the designated text fields but also appeared on the images, which affected their pictorial nature. The handwriting corresponds with the motifs and must therefore be considered in source criticism.