- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

Contexts, Conditions,

and Politics of Postcards

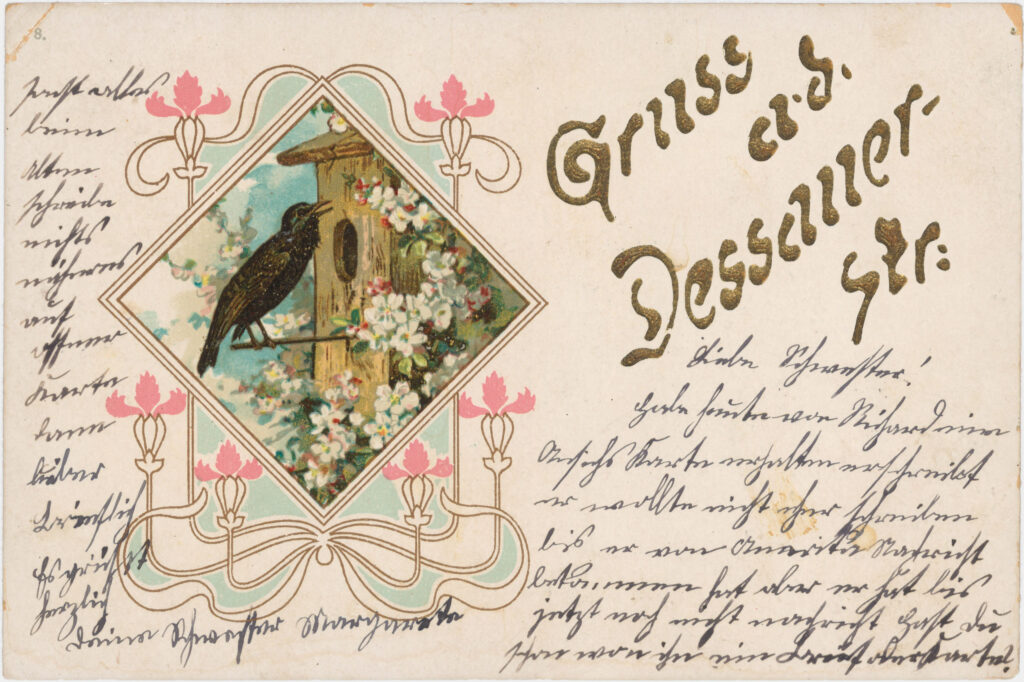

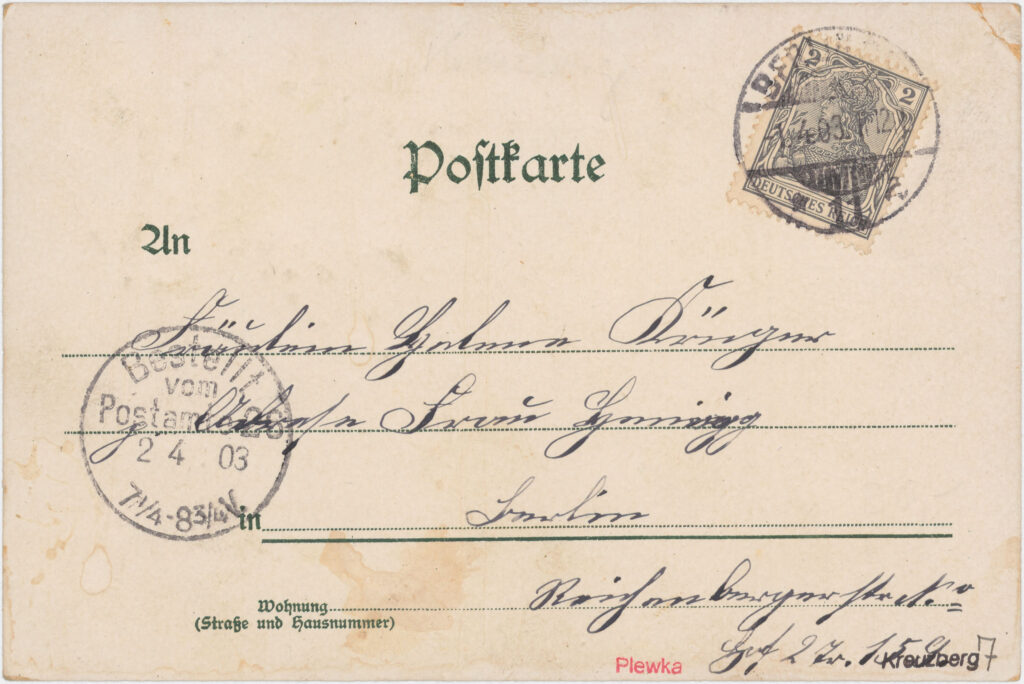

The picture postcards in Peter Plewka’s collection were mostly printed and sent between 1890 and 1945. The first postcard ever was sent in 1869 by the Austrian-Hungarian postal service. Initially, “correspondence cards” without motifs circulated, where both the front and back sides were used for address and text. The first postcards with images were still written on. The separation into a picture side and a text side for all handwritten content only became established in 1905. These postcards are now called “picture postcards.”

Around 1900, approximately 500 million postcards were sent in the German Empire. The rapid spread of the postcard was linked to increasing mobility in both national and international contexts. The postcard quickly became a mass medium: industrialization and compulsory military service drew people to cities, where they maintained contact with their families via postcards. The colonial expansion of the German Empire also led to a demand for images and reports about it. Communication through picture postcards is a historical expression of these developments.

The peak phase of the picture postcard in the German Empire lasted approximately from 1900 to 1914. Nevertheless, German soldiers sent about 10 billion field postcards during World War I. After the war, the significance of the picture postcard declined due to the difficult economic situation. Moreover, new visual media such as illustrated magazines and collectible cards emerged.

Cultural Criticism

The success of the postcard also brought criticism: this form of communication was seen as a threat to the social and advanced culture. Critics viewed postcards as a loss of the emotional intimacy of a letter. The public readability of texts on postcards was considered obscene. Critics lamented the triviality of postcard texts, which they believed distracted from real life. The images were also criticized for distorting reality. Supporters saw in the picture postcard opportunities for maintaining immediate contact with recipients and conveying more vividness than words could.

The debates between supporters and critics can be understood as a symptom of a culture war associated with the development of mass culture around 1900. It also involved struggles over interpretive authority between (educated) bourgeois and proletarian milieus. The letter was considered a medium of the bourgeoisie, while the postcard crossed class boundaries, partly due to lower postage costs.

Development of Design

Before 1905, the address was written on an entire side of the postcard. The other side was only intended for the message text. Over time, small images and illustrations were added to this side of the card, until around 1905, the division of the card with a separate address side became standard.

Motifs

Around 1900, various motifs were printed on picture postcards, such as

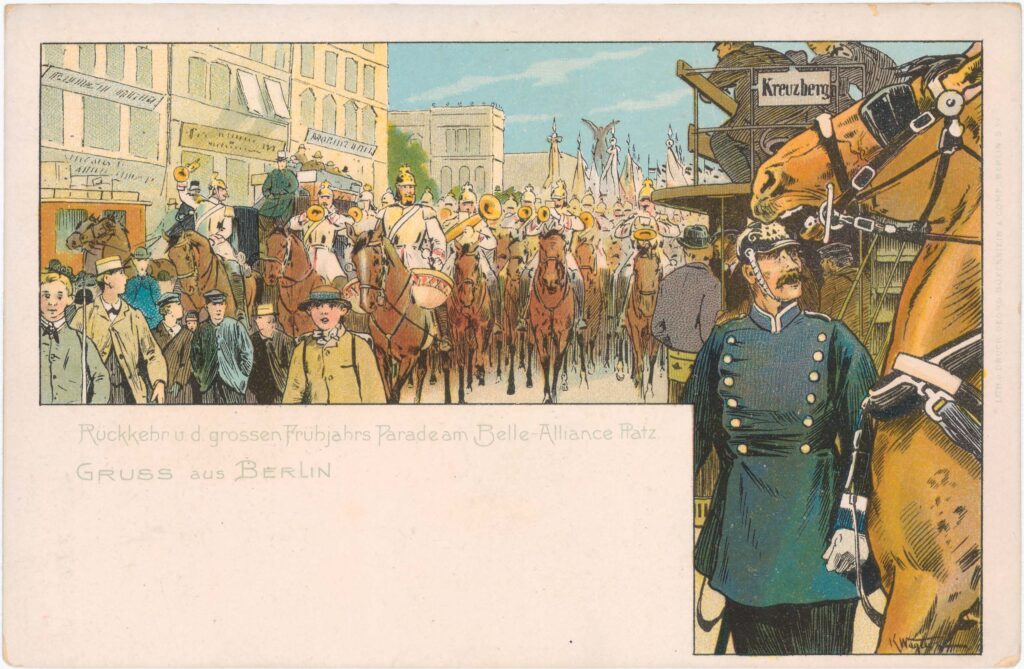

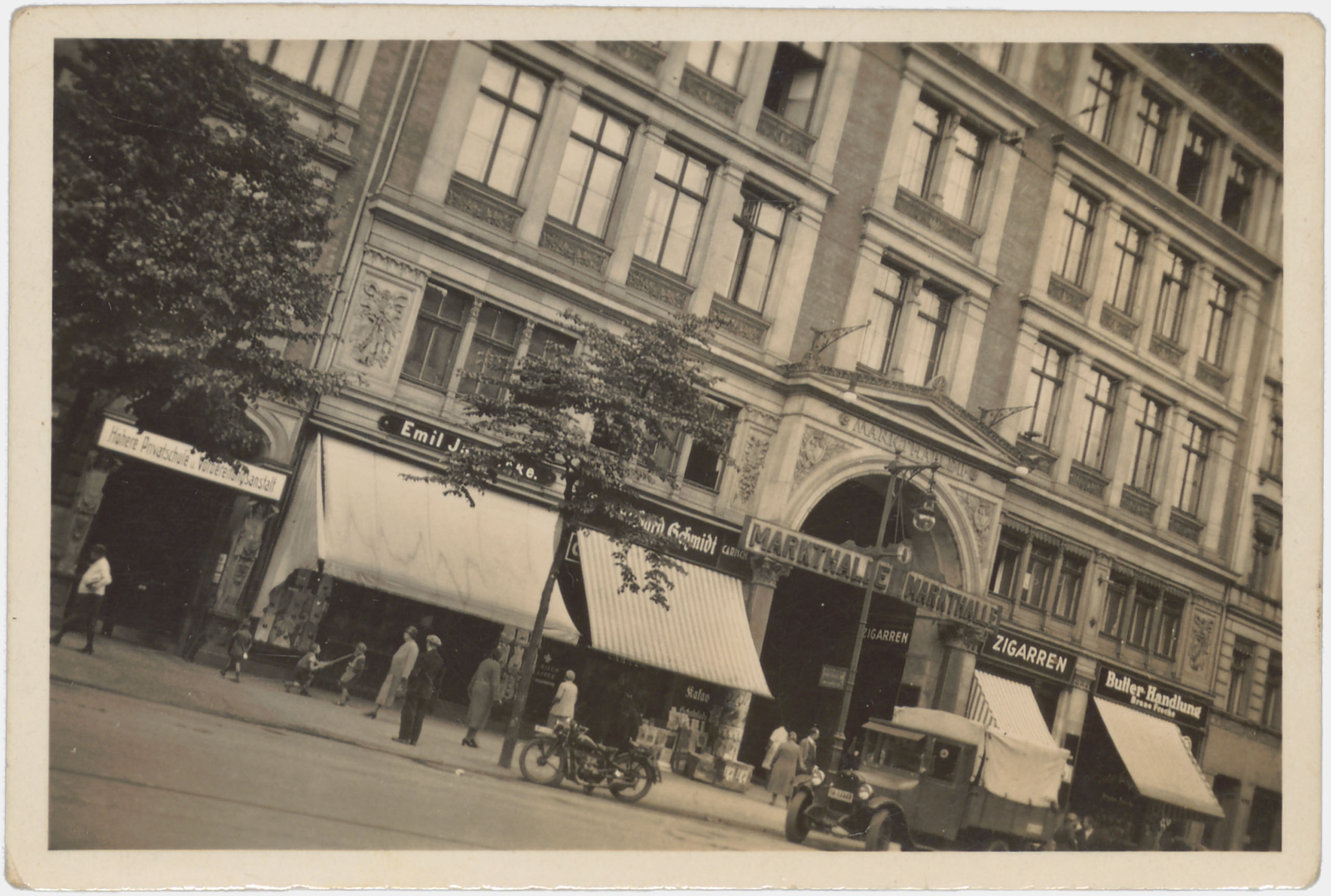

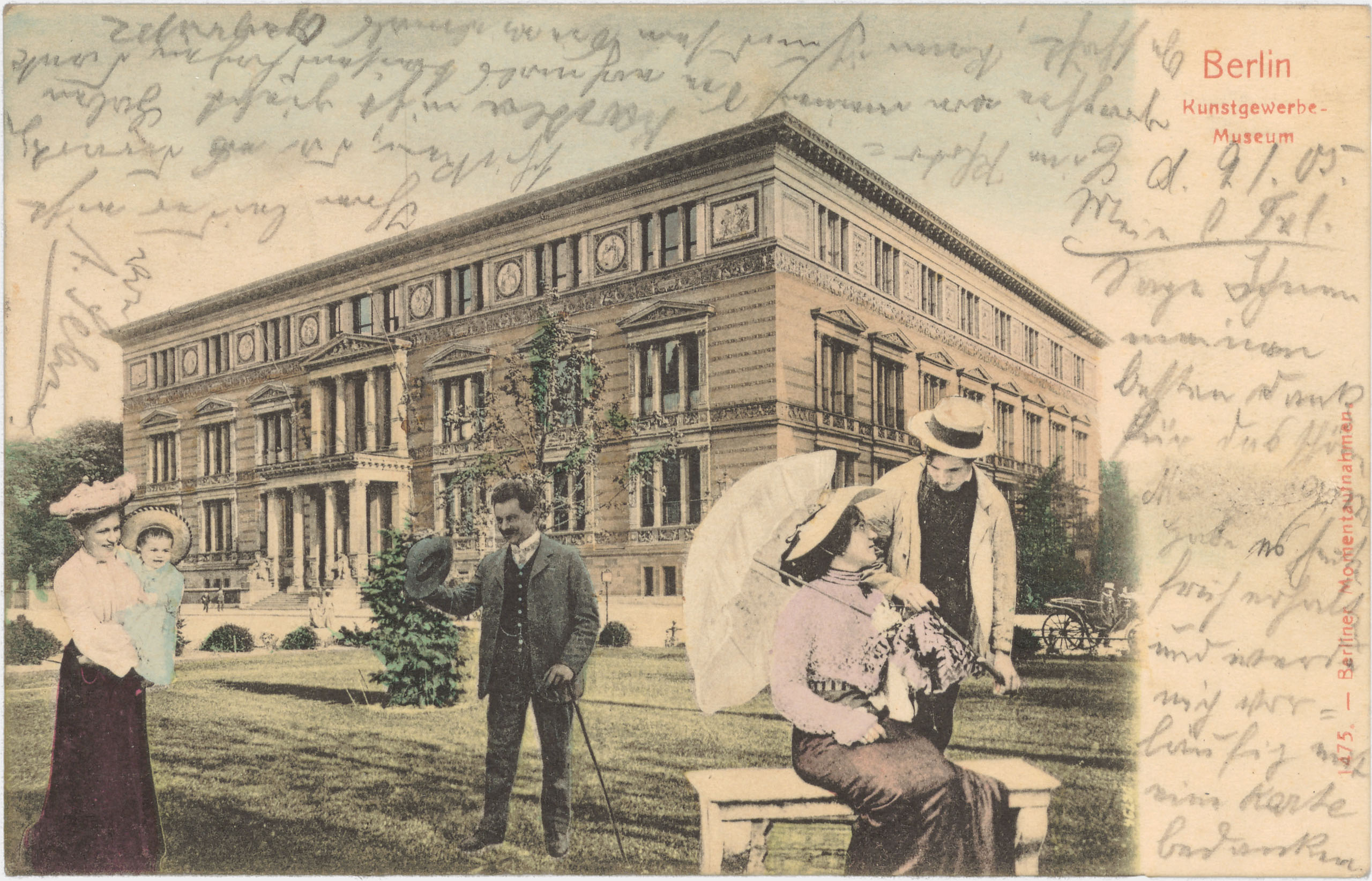

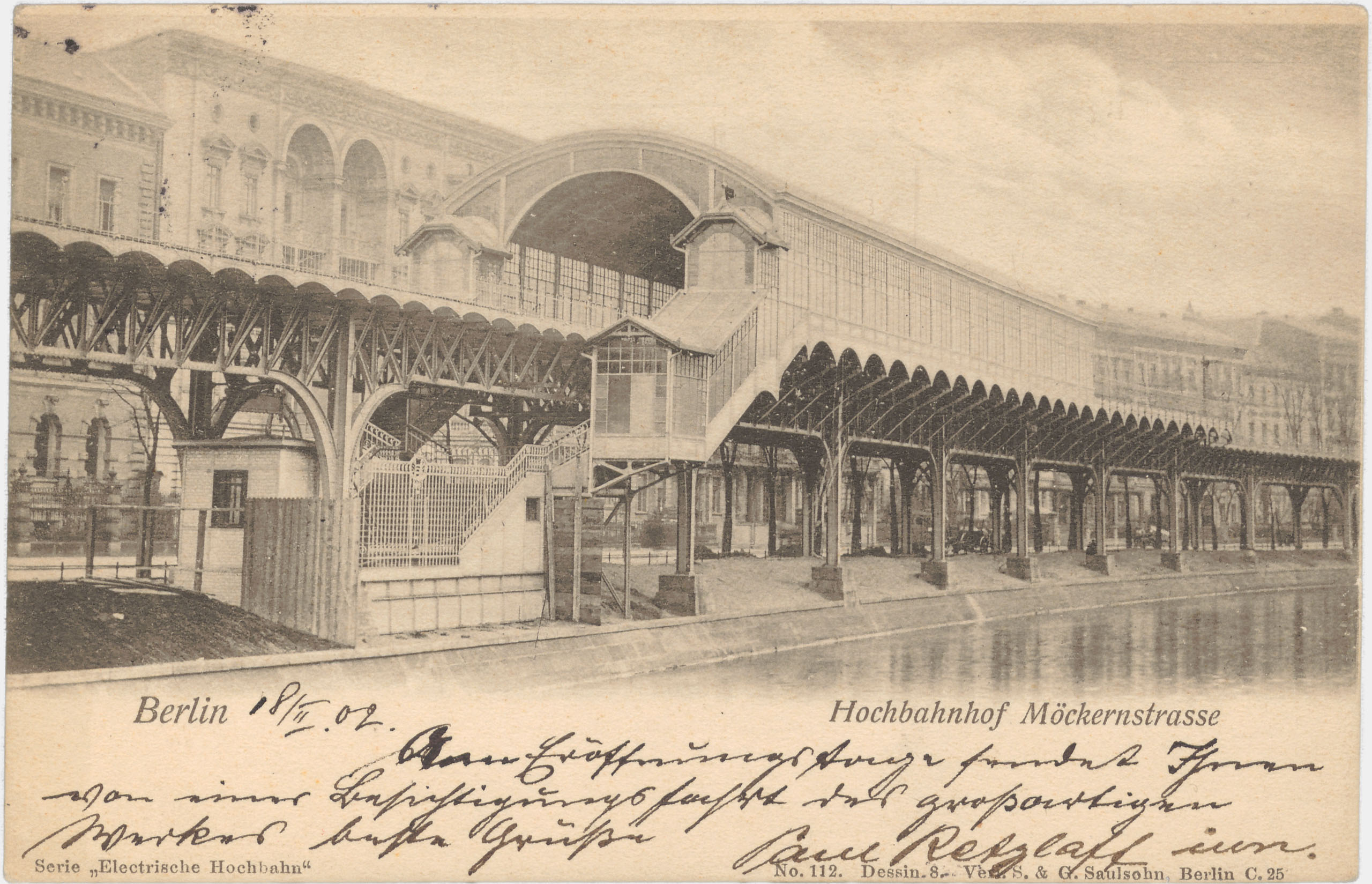

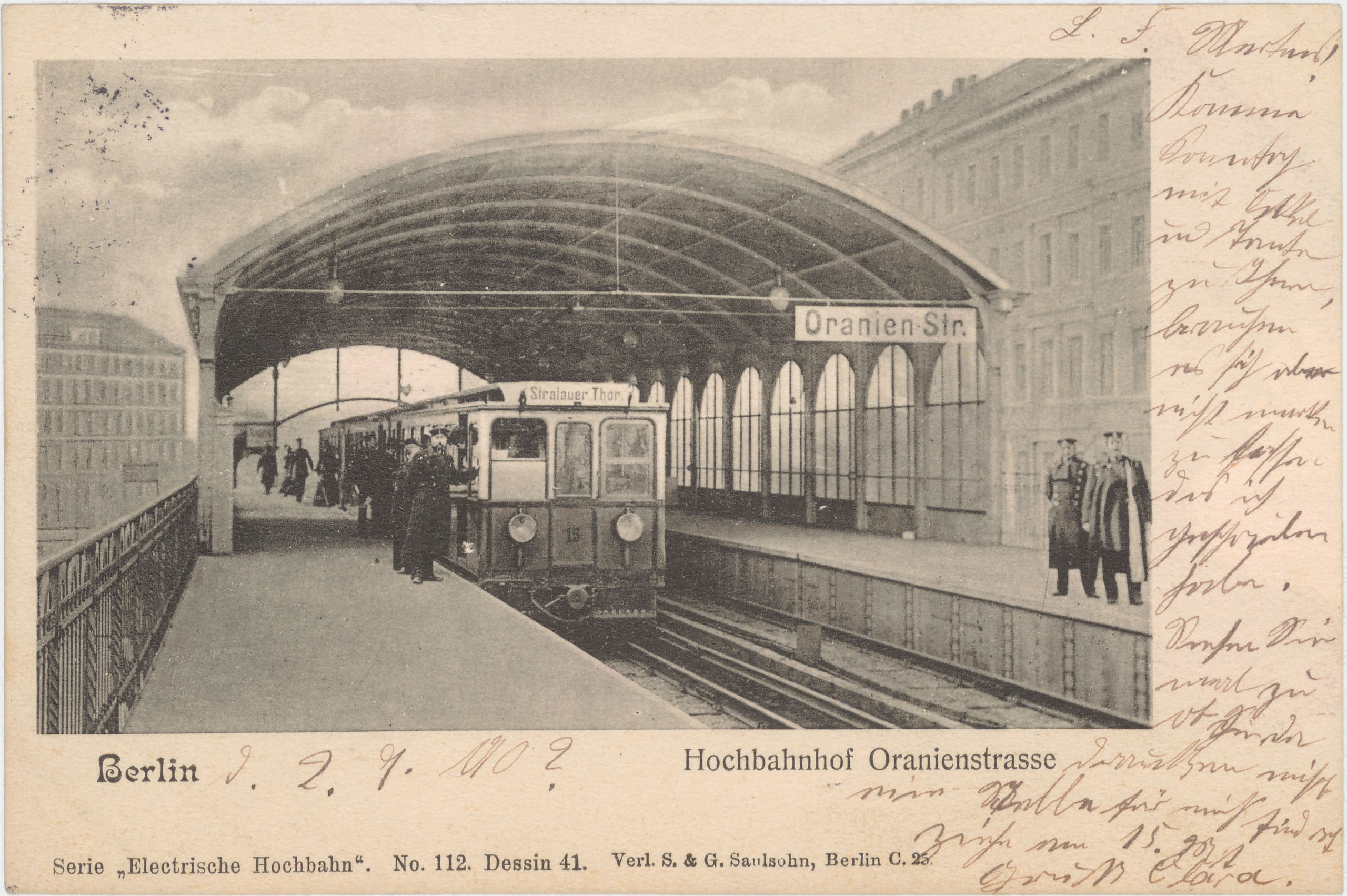

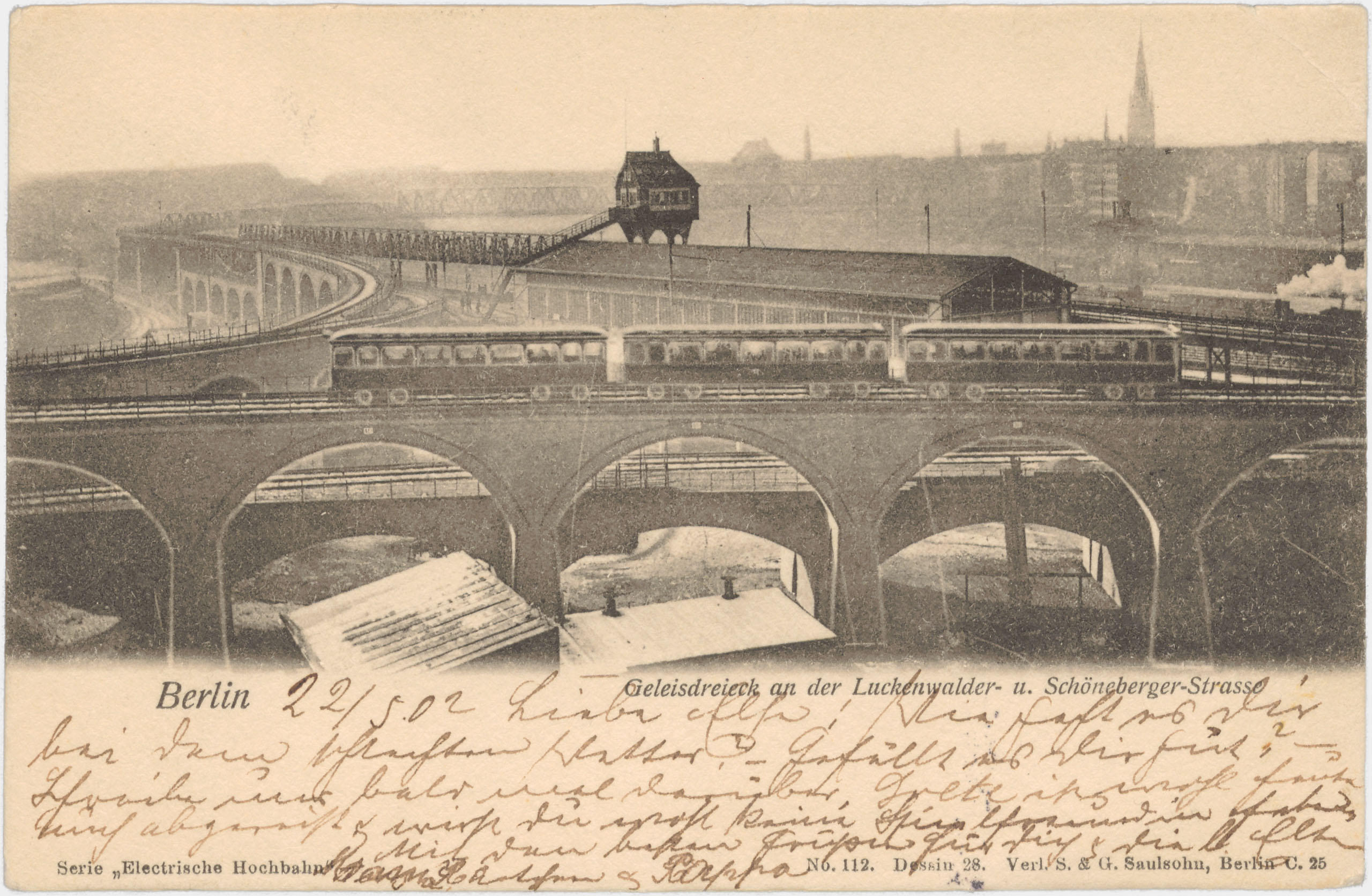

product advertisements, art, sports, caricatures, erotic themes, and propaganda. For a long time, views of buildings and streets as well as depictions of events in urban landscapes were popular. They conveyed an image of the urban space and city life.

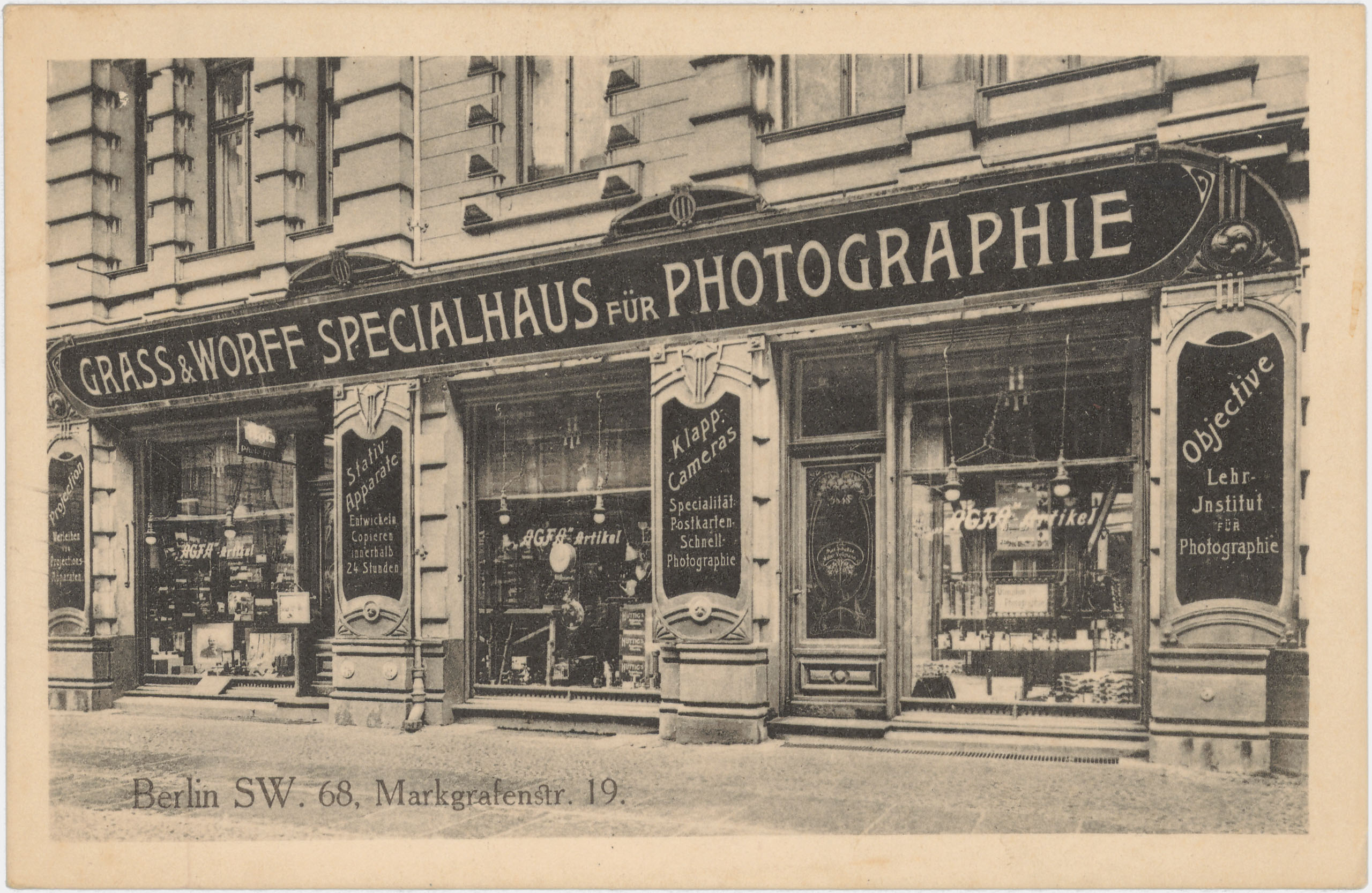

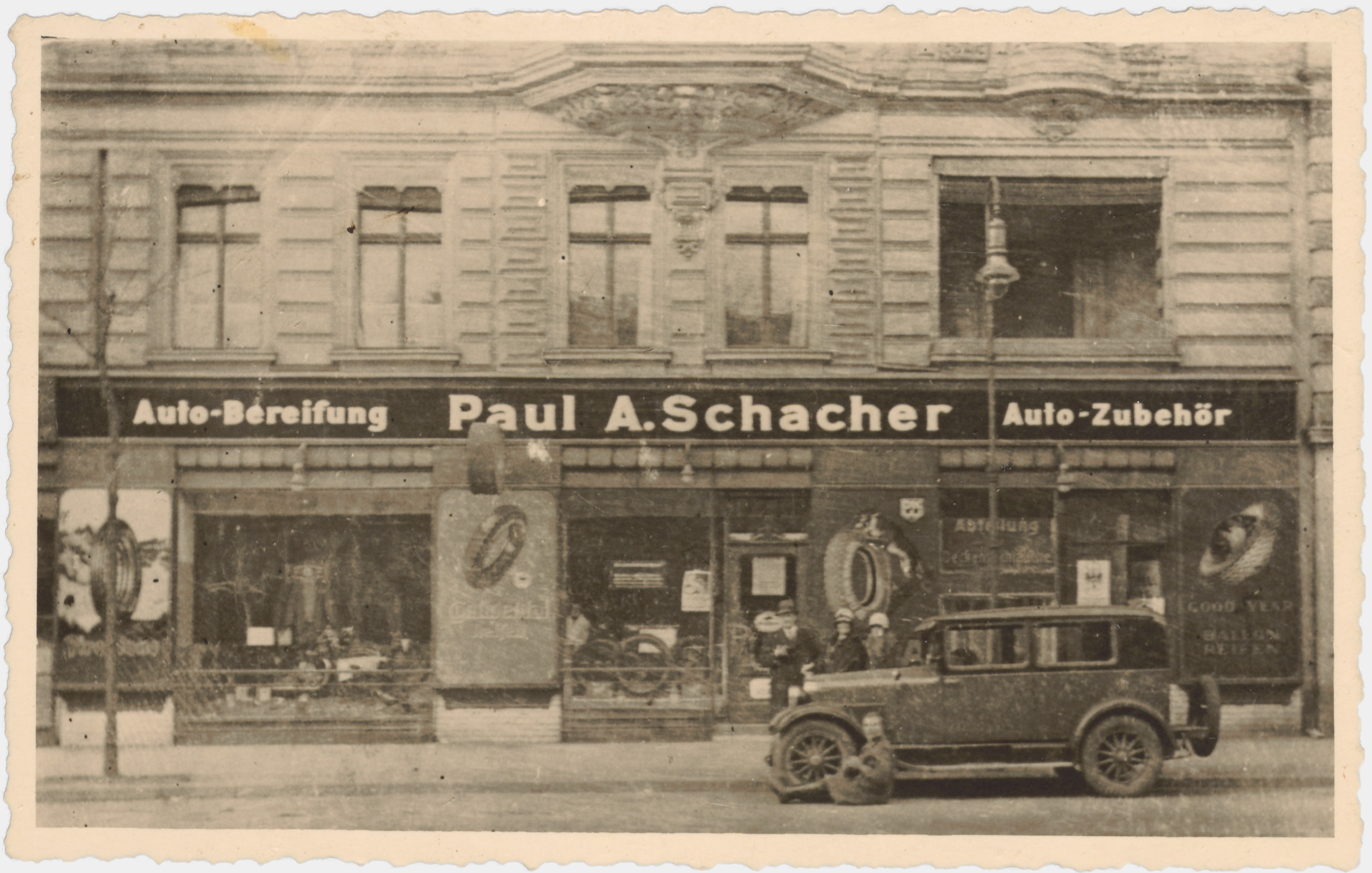

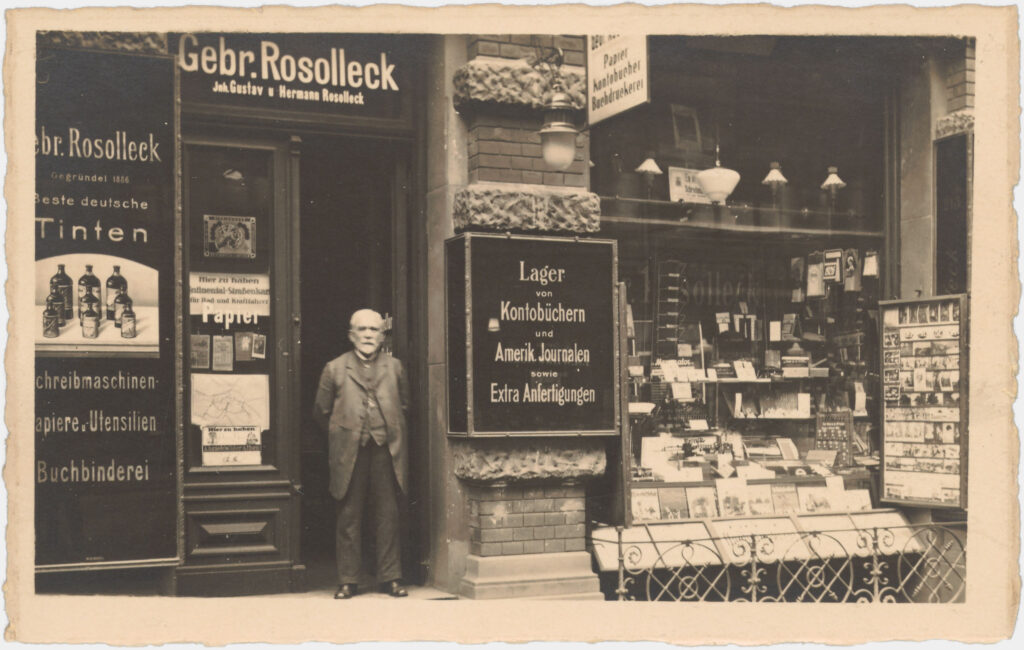

The motifs on picture postcards were guided by demand and were created without central control. They emerged from various occasions, such as political campaigns of individual parties or as advertisements for businesses, and were produced on commission or on one’s own initiative. Commercial photographers scoured the city around 1900, offering shots of houses and businesses. Despite the variety and randomness, certain motifs became established through constant repetition. Most images were subsequently retouched and edited.

Topography

In Peter Plewka’s collection, picture postcards with simple

photographs of streets and buildings are particularly prevalent.

Tourism

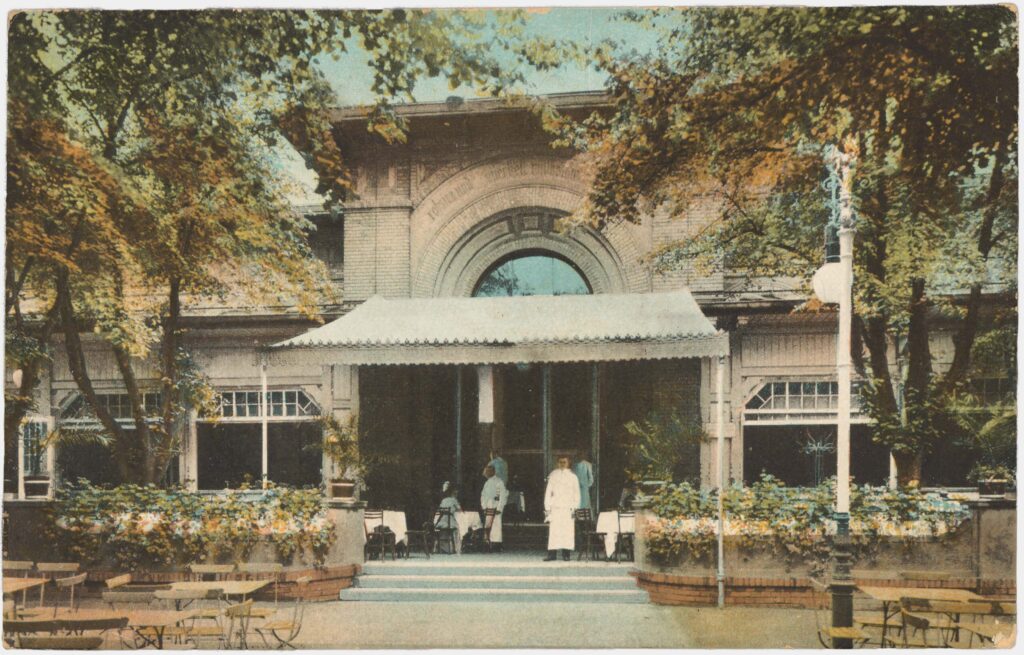

Early as 1900, picture postcards often featured motifs of tourist attractions and landmarks that are still popular today. These cards shaped the image of the changing city by highlighting certain aspects. In particular, the Viktoriapark is frequently depicted on the tourist postcards in Peter Plewka‘s collection.

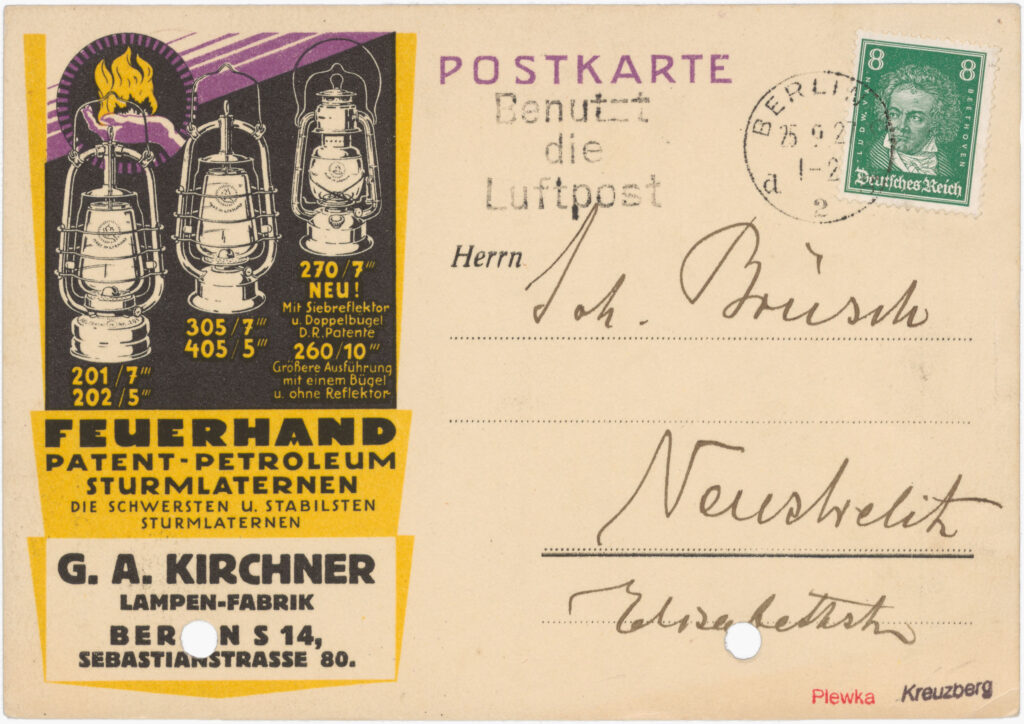

Advertising

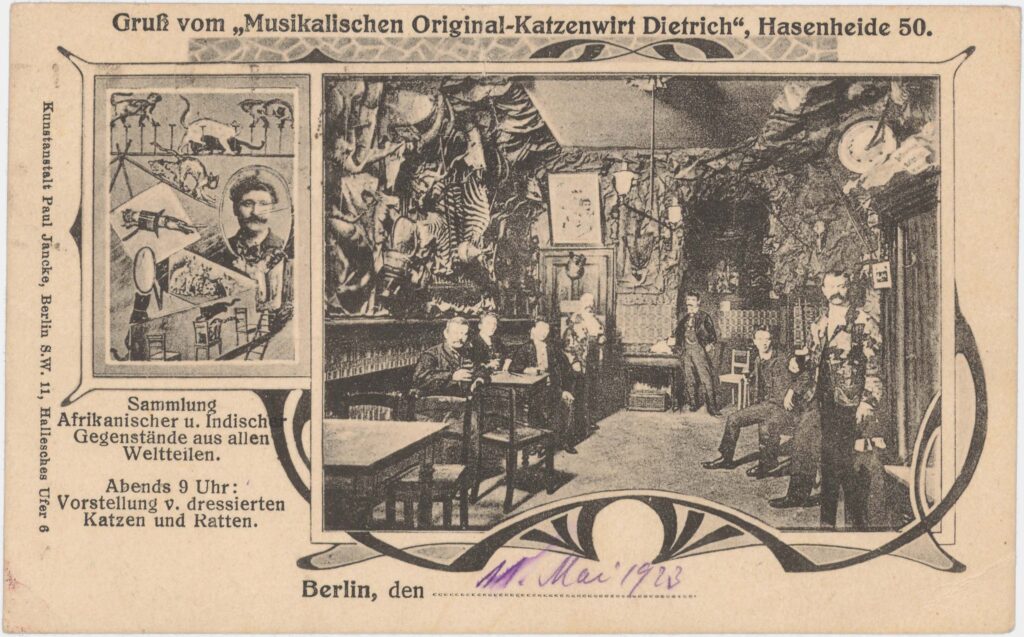

Advertising postcards were used by companies to inform about their product range and to invite people to openings and an-niversary celebrations. Restaurants and entertainment venues used these picture postcards to announce events and present their programs.

Snapshots

Around 1900, photographers roamed cities, capturing whatever they encountered. Sometimes, they also took spontaneous shots for individuals and offered these photographs to publishers. It is therefore likely that many views of streets, buildings, and people were captured spontaneously. This is suggested by the apparently unplanned compositions of the images.

Sensations

Picture postcards often captured special events. Some cards were specifically commissioned by political figures or other organizers. However, important events also attracted photographers who independently took photos and offered them for sale.

Production

The productive, trade, and transportation industries developed rapidly in the modern industrial society of the German Empire. In the second half of the 19th century, there were significant advances in photography and printing technology. Powerful printing technologies enabled high-volume production in a short time, leading to accelerated mass production of picture postcards.

Depending on the motif, various printing methods were used. Since picture postcards were commercial products, popular motifs were printed in large quantities and using more elaborate processes. Despite all the progress, production varied depending on the available technology and the financial resources of the producers. Germany was a center of picture postcard production around 1900, producing 10 million cards annually and selling them both domestically and internationally.

At that time, the production of a picture postcard consisted of three steps: creating a photograph as a negative, editorial, and design processing of the negative, and the technical duplication of the print.

Mass Printing and Overnight Production

With the right equipment, a motif could be turned into a ready-to-use picture postcard within 24 hours. The speed of production also led to postcards with less carefully selected images.

Distribution of Picture Postcards

Around 1900, the sale of postcards in public spaces was widespread. It was not subjected to trade regulations, allowing anyone to sell cards. Peter Plewka’s collection includes several picture postcards showing inscriptions and displays in shop windows.

Printing Techniques

Multi-image postcards were labor-intensive to produce, especially when they included ornaments and greetings. Additional coloring of photographs increased the effort required. In contrast, collotypes with black-and-white motifs were simpler to produce; their captions and other details were simply stamped onto them.

Mail Delivery

The rapidly advancing transportation methods due to industrialization enabled swift mail delivery. Often, delivery took just one day. In cities like Berlin, mail was delivered eight to eleven times a day around 1900. Delivery from the countryside to the city or vice versa took one to three days.

Series as a Sales Strategy

In addition to individual postcards, series of picture postcards were also printed. Card series often had thematic motifs. The idea was to encourage collectors to purchase complete series, thereby increasing sales.