- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

Persecution and Expropriation

of Jews in Kreuzberg

At the turn of the century, many Jews from Eastern Europe (primarily from the Russian Empire, in the area of present-day Ukraine and Belarus) left their homeland after years of pogroms, antisemitism, and discrimination. Most intended to emigrate to the USA, merely passing through what is now Germany. Berlin was one of their stops, but many ended up staying.

Jews had already lived in Kreuzberg before, but with the start of immigration from Eastern Europe, the Jewish population increased significantly, not least due to the low rental prices. With the demographic growth, new synagogues were established in the district: a liberal one on Lindenstraße (1891) and an orthodox one on today’s Fraenkelufer, then Kottbuser Ufer (1916). The new residents expanded the social and cultural life of the community, opened new businesses, and established enterprises.

After Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor and power was transferred to the NSDAP in 1933, the fascist regime introduced prohibitions and laws that severely restricted Jewish life. For example, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service came into effect in April 1933, which led to the dismissal of civil servants of “non-Aryan” descent. Even before this, Jews faced antisemitic discrimination, but from 1933 onwards, this escalated dramatically, culminating in the Nazi’s program envisioning the extermination of all European Jews. After the introduction of the Nuremberg Race Laws in 1935, Jews were no longer considered citizens of the Reich, and were therefore not allowed to own businesses anymore. This forced Jewish entrepreneurs to quit or sell their businesses at a loss of value. Many Jewish employees also lost their jobs, leading to difficult financial situations. Synagogues, cultural institutions, Jewish-owned businesses, and other places of Jewish life were destroyed or damaged, particularly during the November pogroms in 1938. In October 1941, the Nazis began to systematically deport Jews to concentration and extermination camps.

In 1933, 6,000 Jewish people lived in Kreuzberg. In all of Berlin, the number was around 170,000. After the war ended in 1945, only 8,000 Jews remained in Berlin, most of whom had survived by hiding, escaping deportation to concentration camps, and by fleeing from death marchesor Nazi Germany in time.

The postcards from the Peter Plewka Collection show fragments of Jewish life in Kreuzberg. The Holocaust is also reflected in these motifs, even though the images at first glance depict everyday life in Berlin rather than the degradation, discrimination, deportation, and murder of European Jews.

Fraenkelufer Synagogue

The Fraenkelufer Synagogue (then known as the Synagogue at Kottbuser Ufer) was inaugurated in 1916. It was the third orthodox synagogue in Berlin, built due to the influx of many Eastern European Jews. With 2,000 seats, it was one of the largest synagogues in the city and, with its community center, kindergarten, after-school care, and youth club, served as the center of religious and social Jewish life in the area.

Even before the transfer of power, the rising antisemitism in the German society was palpable for the community. On the night of February 15–16, 1930, for instance, the synagogue was defaced with swastikas by regulars of a nearby SA pub. The SA (abbreviation for “Sturmabteilung”), or the so-called “Sturmabteilung”, Storm Division, was a paramilitary organization of the NSDAP from the 1920s onwards, using violence and terror to suppress primarily political opponents. From 1933, it was increasingly integrated into the auxiliary police and the apparatus of power, establishing the first prisons and “wild” concentration camps in Berlin. In 1937, Kottbuser Ufer was renamed Thielschufer after SA member Hermann Thielsch, who died in 1931.

After the Nazis came to power, community members tried to support each other, for example, through a welfare office and a counseling center established in 1933, and a welfare kitchen that opened in 1935. During the November pogroms in 1938, Nazis attempted to set the synagogue on fire, damaging the main synagogue, which forced the next services to be held in the youth synagogue. The last service took place in October 1942.

A year later, the building was heavily damaged by Allied bombing raids. In September 1945, the synagogue’s side wing was reopened. It was officially rededicated in 1959 and has since been known as the Fraenkelufer Synagogue, as the street was renamed in 1947 after the Jewish physician and director of the Urban Hospital, Albert Fraenkel.

Theater of the Jewish Cultural Union

“A European theater, by Jews for Jews, in the capital of Jew-hatred during the Nazi regime.”

Herbert H. Freeden, 1963

Immediately after the NSDAP came to power in 1933, Jews were pushed out of their positions in all areas. With the introduction of the Law of the Reich Chamber of Culture in September 1933, Jewish artists were banned from participating in public cultural life. Nevertheless, in 1933 Kurt Baumann and Kurt Singer founded the Jewish Cultural Union, to continue presenting Jewish art and culture in defiance of the regime—a form of cultural resistance against the Nazi regime. The Berlin neurologist and musicologist Kurt Singer was appointed chairman of the Cultural Union and remained so until the pogrom night in November 1938.

The Theater of the Jewish Cultural Union first opened its doors in 1933 at Charlottenstraße 90–92 and moved to Kommandantenstraße in 1935. The theater’s program was extensive: operas and operettas, plays, concerts, and lectures. However, the scripts for all stage performances had to be approved by Nazi censorship. The Cultural Union was not allowed to perform works by “Aryan” authors and composers. In 1941, the Jewish Cultural Union was forcibly dissolved, and the theater closed.

During the November pogroms, Kurt Singer traveled to the USA. Despite attempts by friends to convince him to stay there, he returned to Europe. He died in 1944 in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. The same fate befell many members of the Jewish Cultural Union. They were deported and murdered in concentration or extermination camps.

Anhalter Bahnhof

The terms “metropolitan station,” “gateway to the south,” “platform of tears,” and “refugee station” are used today to remember Anhalter Bahnhof. Since its opening in 1841, the station has been known by various names. For some, it was the station from which private journeys near and far began, while for others, it was the station from which they would leave their homes forever. In the Jewish history of Berlin, the station played a central role: it was from here that Jews initially fled into exile. It was also the starting point for the first so-called Kindertransporte (children’s transports) — an initiative that allowed German-Jewish children to emigrate to Great Britain between 1938 and 1939; over 4,000 children were thus saved from imprisonment, forced labor, and death in Germany. But between 1942 and 1945, deportation trains also departed from here, carrying mostly elderly Jews to Theresienstadt. The Gestapo (Secret State Police) forced them to pay their own travel expenses. In total, nearly 10,000 people were deported from here, about three percent of whom were from Kreuzberg.

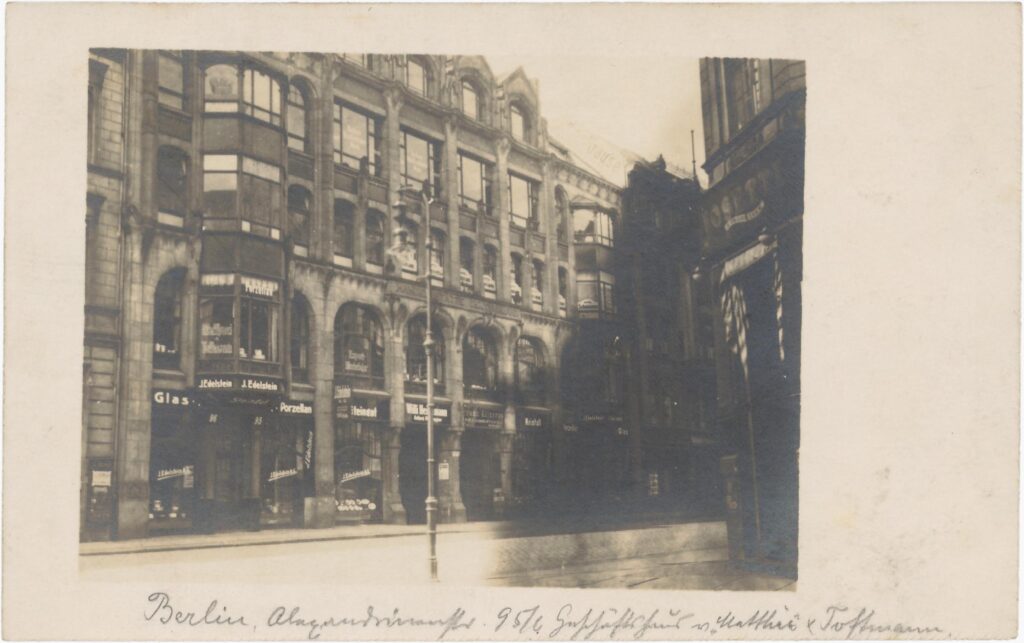

Julius Edelstein Porcelain Factory

In 1919, Julius Edelstein, along with his business partner Isidor Grünebaum, purchased a porcelain factory in Bavaria, and four years later, they acquired the Glass, Porcelain, and Stoneware Trading Corporation based in Kreuzberg, at Alexandrinenstraße 95–96. This was also the location of the Berlin branch of his porcelain factory. Edelstein’s porcelain tableware was known for its high quality and was very popular.

In 1926, Edelstein AG took out a loan from the Colditz AG stoneware factory, placing them in financial dependency on Colditz. Due to the Great Depression of 1929, Colditz forced Edelstein AG into bankruptcy in 1932 and took over their factories, even though the loans had always been repaid on time. Julius Edelstein received only partial compensation in the form of shares in the Beyer & Bock porcelain factory, which he managed from 1933 onwards. However, after the Nazis came to power, he had no means to influence the bankruptcy proceedings in his favor.

The NSDAP member Fritz Greiner took over management in 1932/1933 and remained in charge until 1971, with a five-year break after the war ended. In 1934, the company’s headquarters moved from Berlin to Bavaria.

During the November pogroms in 1938, Julius Edelstein was briefly arrested; afterward, he went into hiding. His children, Marianne and Werner, emigrated between 1934 and 1935—Werner to Palestine and Marianne first to Switzerland and later, at the end of 1938/beginning of 1939 (after a brief return to Germany), to Great Britain, two years before the emigration ban for Jews was enforced. After the war, the Edelstein children emigrated to the USA.

Julius Edelstein and his wife Margarete were deported to Riga in November 1941 and murdered there. The Porcelain Factory AG continued under the Edelstein name throughout Nazi Germany. The name had stood for quality even before the Nazi era, which is why it was retained even after the “Aryanization.” The company continued its activities under various parent companies in the post-war years and was dissolved in 1973.

Author

Marina Kochedyshkina

MA Public History

LITERATURE

Freunde der Synagoge Fraenkelufer e. V.: 100 Jahre Synagoge am Fraenkelufer: ein Jahrhundert jüdisches Leben in Kreuzberg 1916 – 2016. Berlin 2016.

Bernd Wollner, Achim Bühler: 170 Jahre Porzellan. Wie Küps Geschichte machte. Küps 2001.

Gauding, Daniela/Zahn, Christine: Die Synagoge Fraenkelufer.

Freeden, Herbert: Jüdisches Theater in Nazideutschland.

Tübingen Mohr (Siebeck).

Ludwig, Andreas/Christine Zahn/Dagmar Bolz: Juden in Kreuzberg: Fundstücke .., Fragmente .., Erinnerungen .. ; [Katalog zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung vom 18. Oktober bis 29. Dezember 1991 im Kreuzberg-Museum (in Gründung) Berlin]. 1991.

The New York Community Trust (Hrsg.): Marianne Edelstein Orlando 1918–1990.New York o. J.

Peters, Dietlinde: Der Anhalter Bahnhof als Deportations-Bahnhof. Berlin 2011. Bezirksmuseum Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. S. 10–70.