- Homepage

- Topics

- National socialism in everyday life in Kreuzberg

- Communist working-class milieu

- Persecution and expropriation of Jews in Kreuzberg

- Paula Thiede and the newspaper district

- Lisa Fittko’s Kreuzberg neighborhood

- November Revolution

- Disaster Images

- Kreuzberg Garrison

- Queer in the Weimar Republic

- Trade, Craft, and Industries

- Colonial Kreuzberg

- Women in Kreuzberg

- Technology & Faith in Progress

- Archive

- About the Project

DISASTERS ON POSTCARDS

The Cloudburst of 1902 and the

Elevated Railway Accident of 1908 in Berlin

Disasters are among the topics that are present in today’s news media and are shared by social media users. The internet provides the possibility to find shocking images and even live broadcasts of devastating events. In today’s digital world, memes and social media posts are used to comment events such as disasters in a humorous or critical way. At the beginning of the 20th century, postcards fulfilled a similar function as today’s media, namely the depiction of events through the combination of image and text. They not only served to document events but also articulated and anticipated public reactions.

Until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, several billion postcards with various motifs were produced, sold, and sent in the German Empire. The depiction of disasters on postcards had multiple effects: they could create a sense of solidarity among victims and their relatives through shared experiences. Additionally, the dissemination of disaster images on postcards could spark public discussion about the respective events. For those who did not learn about the event through newspaper reports, a postcard with an appropriate motif could visually bring the event to life. However, images of disasters also aimed to shock and simultaneously satisfy the sensationalism of their viewers.

Postcards play a significant role in collective memory and identity, as they massively spread images of certain events, seemingly documenting reality. However, the motifs of postcards stage reality due to their composition, the selected image sections, and through image editing.

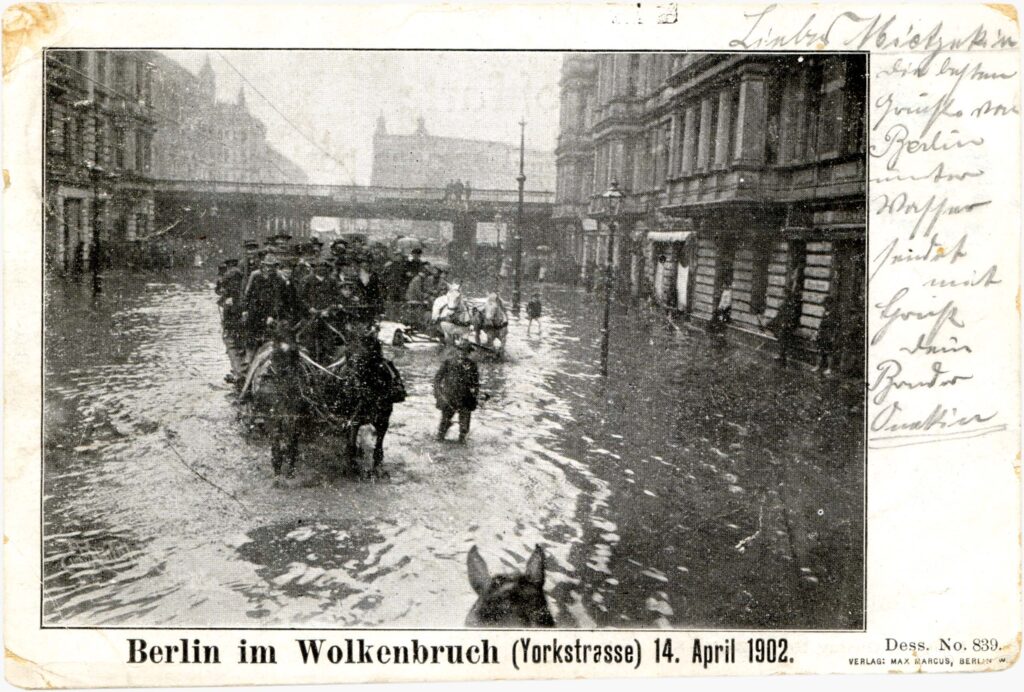

The period between about 1900 and 1920 can be seen as the heyday of postcards. Postcards could be produced and sold cheaply due to technical innovations, and frequent mail deliveries allowed cards to be delivered within a few days or, in larger cities, on the same day. The postcards selected here from 1902 and 1908 were created during this phase. The postcards depict two disasters in Berlin, one technical and one natural disaster. The two events were depicted differently, in one case more humorously, in the other more documentary. One motif is the flood of 1902, and the other is the elevated railway accident at Gleisdreieck in 1908.

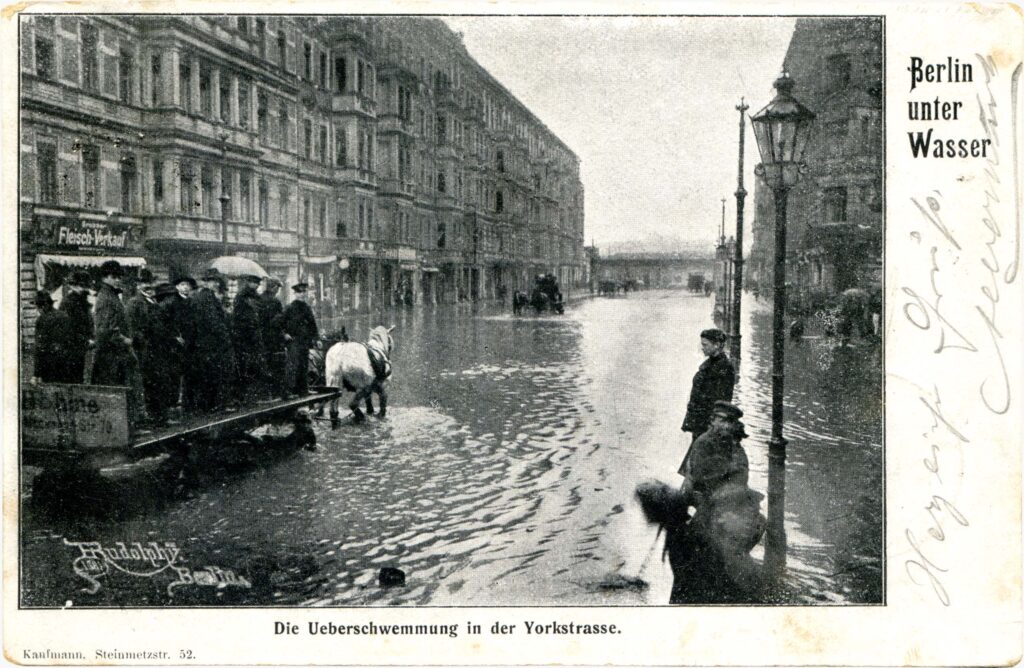

Flooding in Berlin on April 14, 1902

Meteorologists predicted calm weather for April 14, 1902, yet starting at 3 a.m., the capital was awakened by rain, lightning, and floods. Large parts of Berlin were flooded, and Kreuzberg was affected in many areas. In Viktoriapark, the storm caused significant damage. In several districts, cellars and basement apartments were underwater. The fire brigade was alerted on an unprecedented scale, and by 8 a.m., all of the city’s fire fighting units were in use. They were called to Katzbachstraße 5 because the collapse of the four-story house was feared, for example. On Yorckstraße, the water was one meter high from Katzbachstraße to Bülowstraße by noon. At Friedrichstraße station, porters offered to carry pedestrians over the worst spots for a modest tip.

A publisher turned the aftermath of the flood into an anecdote; they produced a postcard on which a man at Katzbachstraße 5 unintentionally became a meme of his time: according to the Berliner Tageblatt and Handels-Zeitung of April 14, 1902, he had to be rescued from the flooding of his apartment by his neighbors due to his drunken state. This story was reported in newspapers and was also turned into a caricature through the postcard.

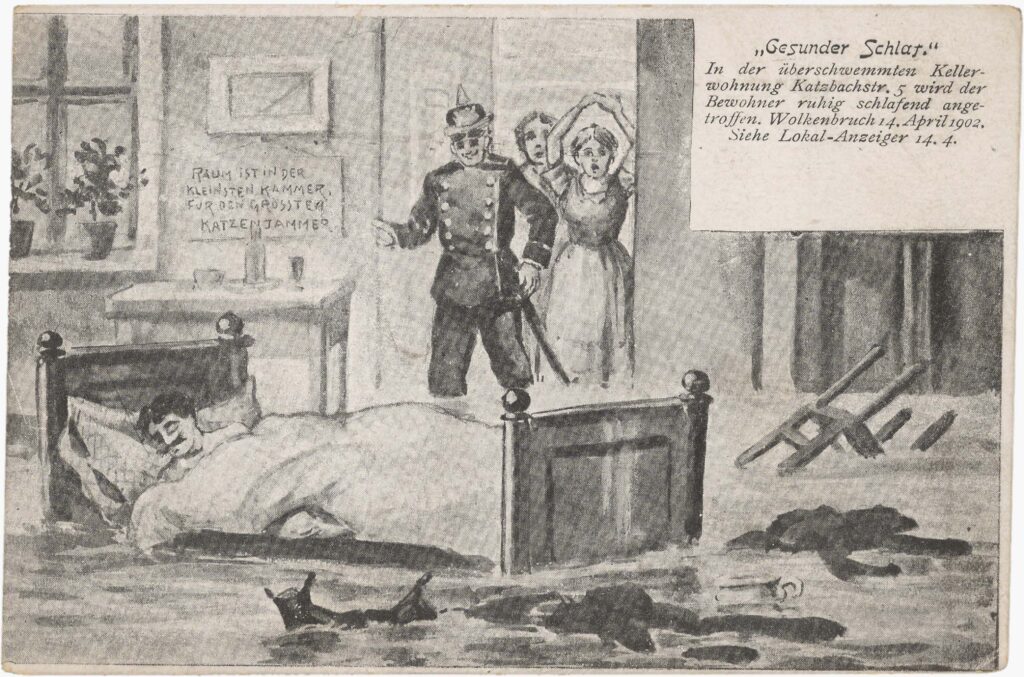

Flooding

The postcard shows an image of a sleeping man in a flooded room. In the doorway stand an officer and two women. The depiction recreates the scene of a real story reported by the Berliner Tageblatt. In Katzbachstraße 5, a drunken man was surprised in bed by a flood. A text field with a pun “There’s room in the smallest chamber for the greatest Katzenjammer” further contributes to the humorous depiction of the postcard by referencing the connection between “Katzenjammer” and “Katzbachstraße.” The rhyme also seems fitting because “Katzenjammer” (also “Kater” in colloquial language, meaning hangover) refers to the discomfort after excessive alcohol consumption. This postcard illustrates both the extent of the disaster and the attempt to cope with the dramatic situation through humor.

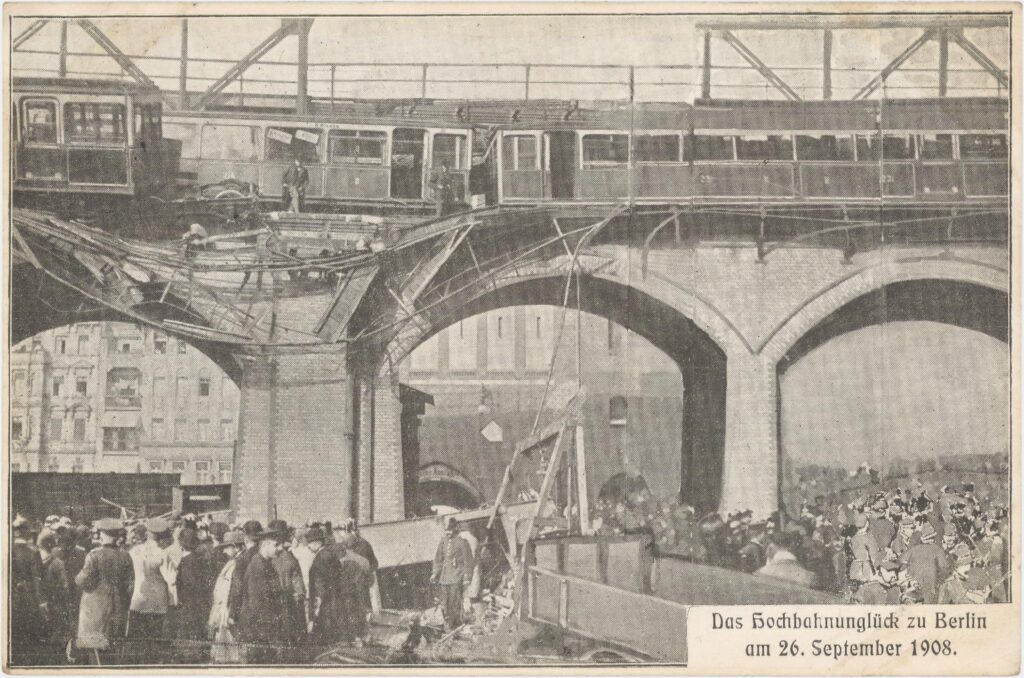

Elevated Railway Accident

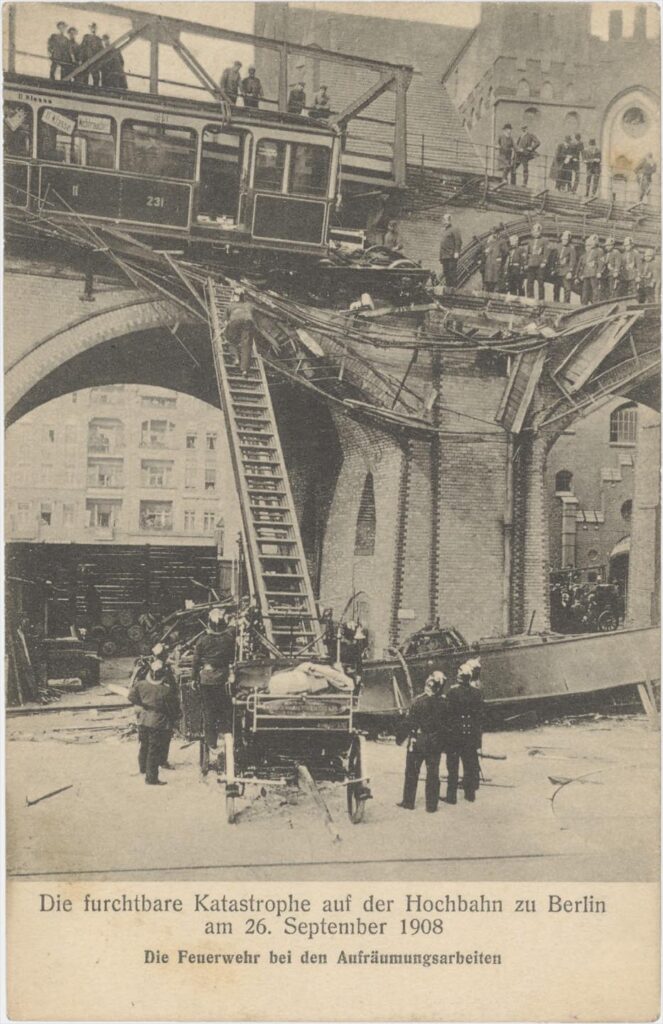

In 1902, Germany’s first elevated and underground railway line ran through the Gleisdreieck area in Kreuzberg. The name “Gleisdreieck” was derived from the intersection of three subway lines. The elevated railway gained tragic fame on September 26, 1908, due to a severe accident.

At 1:42 p.m., a train departed from Potsdamer Platz toward Warschauer Brücke, ignoring two stop signals. As a result, it was rammed by a train coming from Bülowstraße at the connecting switch, and one car plunged into the courtyard of the “Gesellschaft für Markt- & Kühlhallen”. Additionally, the clutch between two cars of the Bülowstraße train broke. In total, 21 people died, and more than 20 were seriously injured.

In the Berliner Tageblatt and Handels-Zeitung of September 26, 1908, a passenger reported that a terrible crash was suddenly heard, and the train came to an abrupt stop. When he looked out the window, he saw an elevated railway car beneath him, with its wheels pointing upward. Immediately afterward, the car completely collapsed, crushing the numerous passengers inside, and heart-wrenching screams were heard under the rubble. He quickly left the train with the other passengers to get to safety.

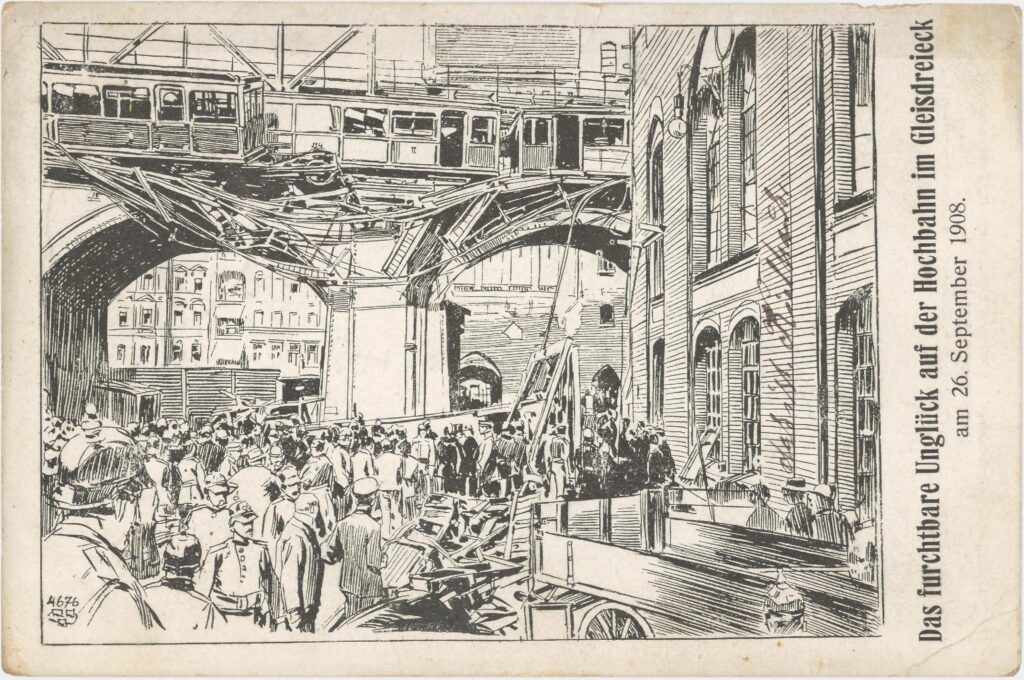

Peter Plewka also collected postcards related to this event, whose dramatic consequences became the subject of several postcards. These showed various perspectives. Using different methods such as photography and illustration, they highlighted the severity of the accident.

It can be argued that the postcards about the elevated railway accident were distributed as reports and sources of information. The elevated railway, which had been considered absolutely safe until then, was discussed in public after the railway accidents of 1908 and 1911. As a result, in 1911 and 1912, structural measures were taken at Kreuzbahnhof at Gleisdreieck to increase safety for rail travelers, which were completed on November 3, 1912.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the elevated railway was considered evidence of progress and was part of the city’s modernization, as it enabled fast transportation for the growing population. Accidents like the elevated railway disaster of 1908, however, were seen by modernization skeptics of the time as evidence of the dangers and risks of urban life.

The postcard shows a scene illustrating the tragic consequences of the elevated railway disaster. As a result of a particularly violent collision, the front car of the impacted train was torn off the track and plunged into the depths. The wagon crashed into the courtyard of the property at Luckenwalder Straße 2.

The motif of the postcard shows the structural damage and firefighters at the scene. The text at the bottom of the image provides additional information about their tasks. A fire department ladder can be seen on the postcard during its deployment. It is also evident that the second wagon above was in danger of falling. The postcard seems to focus on the rescue efforts and the techniques used.

The scene depicted here shows the train damaged by the accident in a dramatic manner. The image also points to the numerous onlookers and helpers who are also visible in photographic postcard motifs. The crowd consists of firefighters, men in hats and suits, as well as workers, indicating the diversity of social classes and professions. The motif is realistically designed and could suggest that the publisher wanted to highlight the helpfulness and solidarity of the Berlin population as well as focus on the eyewitnesses of this event.

Author

Christina Helwig

MA Public History

LITERATURE

Braun, Gustav: Die Stammlinie der elektrischen Hoch- und Untergrundbahn. In: Verkehrstechnische Woche, 3. Jahrgang, Nr. 2 (10. Oktober 1908). S. 17f.

Chod, Kathrin/Schwenk, Herbert/ Weißpflug, Hainer: Berliner Bezirkslexikon Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. Berlin 2003. Haude & Spener. S. 175—176.

Glatzer, Dieter/Glatzer, Ruth: Berliner Leben 1900 – 1914: eine historische Reportage aus Erinnerungen und Berichten. Berlin 1986. Rütten&Loening. S. 198–200.

Holzheid, Anett: Die Postkarte als text- und bildkommunikatives Phänomen. In: Matthews-Schlinzig, Marie Isabel u. a.: Handbuch Brief: Von der Frühen Neuzeit bis zur Gegenwart. Berlin/Boston 2020. Walter de Gruyter GmbH. S. 409.

Kaak, Heinrich: Kreuzberg. in: Ribbe, Wolfgang (Hg.): Geschichte der Berliner Verwaltungsbezirke, Band 2. Berlin 1988. Colloquium Verlag. S. 68–70.

Kaddoura, Dieter: U1. Geschichte(n) aus dem Untergrund, Berlin 1995. Gesellschaft für Verkehrspolitik und Eisenbahnwesen (GVE) e.V. S. 36—39.

Von Hagenow, Elisabeth: Die Postkarte als Propagandamedium im internationalen Vergleich. In: Gold, Helmut, und Backhaus, Fritz (Hg.): Abgestempelt – Judenfeindliche Postkarten: auf der Grundlage der Sammlung Wolfgang Haney. Heidelberg 1999. Umschau/Braus. S. 299.

Berliner Neueste Nachrichten. Nr. 172. 22. Jahrgang. Abend-Ausgabe. Montag 14. April 1902. S 2–3.

Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung. Nr. 187. XXXI Jahrgang. Abend-Ausgabe. Montag 14. April 1902. S. 6. (Bericht über einen angetrunkenen Mann in der Katzbachstraße 5, der von der Feuerwehr und seinen Nachbar*innen aus der Wohnung getragen wurde aus den B und C-Texten.)

Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung, Nr. 188, XXXI Jahrgang, Morgen-Ausgabe, Dienstag 15. April 1902. S. 5.

Volkszeitung, Nr. 172. Abendblatt. 1902. – Berlin 50. Jahrgang, Montag 14. April 1902. S. 1–2.

Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung, Nr. 492, 37. Jahrgang, Abend-Ausgabe, Sonnabend 26.09.1908, S. 4. (Bericht eines Fahrgastes/Augenzeugen aus dem B-Text)

https://www.ausstellung-postkarte.de/ (abgerufen am 14.07.2024)